Anthocyanin

[7][8] Tomato plants protect against cold stress with anthocyanins countering reactive oxygen species, leading to a lower rate of cell death in leaves.

[7] The absorbance pattern responsible for the red color of anthocyanins may be complementary to that of green chlorophyll in photosynthetically active tissues such as young Quercus coccifera leaves.

[10][11] Sometimes bred purposely for high anthocyanin content, ornamental plants such as sweet peppers may have unusual culinary and aesthetic appeal.

[14] Plants rich in anthocyanins are Vaccinium species, such as blueberry, cranberry, and bilberry; Rubus berries, including black raspberry, red raspberry, and blackberry; blackcurrant, cherry, eggplant (aubergine) peel, black rice, ube, Okinawan sweet potato, Concord grape, muscadine grape, red cabbage, and violet petals.

[29][30][31][32] Anthocyanins are less abundant in banana, asparagus, pea, fennel, pear, and potato, and may be totally absent in certain cultivars of green gooseberries.

[16] The highest recorded amount appears to be specifically in the seed coat of black soybean (Glycine max L.

containing approximately 2 g per 100 g,[33] in purple corn kernels and husks, and in the skins and pulp of black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa L.) (see table).

Due to critical differences in sample origin, preparation, and extraction methods determining anthocyanin content,[34][35] the values presented in the adjoining table are not directly comparable.

Nature, traditional agriculture methods, and plant breeding have produced various uncommon crops containing anthocyanins, including blue- or red-flesh potatoes and purple or red broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, carrots, and corn.

[36] Investing tomatoes with high anthocyanin content doubles their shelf-life and inhibits growth of a post-harvest mold pathogen, Botrytis cinerea.

[39] Content of anthocyanins in the leaves of colorful plant foods such as purple corn, blueberries, or lingonberries, is about ten times higher than in the edible kernels or fruit.

Unlike carotenoids, anthocyanins are not present in the leaf throughout the growing season, but are produced actively, toward the end of summer.

[2] They develop in late summer in the sap of leaf cells, resulting from complex interactions of factors inside and outside the plant.

[5][50][51] Unlike controlled test-tube conditions, the fate of anthocyanins in vivo shows they are poorly conserved (less than 5%), with most of what is absorbed existing as chemically modified metabolites that are excreted rapidly.

[52] It is possible that metabolites of ingested anthocyanins are reabsorbed in the gastrointestinal tract from where they may enter the blood for systemic distribution and have effects as smaller molecules.

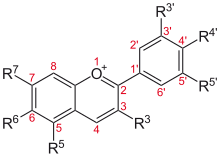

[54] B-ring hydroxylation status and pH have been shown to mediate the degradation of anthocyanins to their phenolic acid and aldehyde constituents.