Human evolution

[4][5][6][7] The study of the origins of humans involves several scientific disciplines, including physical and evolutionary anthropology, paleontology, and genetics; the field is also known by the terms anthropogeny, anthropogenesis, and anthropogony[8][9]—with the latter two sometimes used to refer to the related subject of hominization.

David R. Begun[24] concluded that early primates flourished in Eurasia and that a lineage leading to the African apes and humans, including to Dryopithecus, migrated south from Europe or Western Asia into Africa.

[26] In 2010, Saadanius was described as a close relative of the last common ancestor of the crown catarrhines, and tentatively dated to 29–28 mya, helping to fill an 11-million-year gap in the fossil record.

[27] In the Early Miocene, about 22 million years ago, the many kinds of arboreally-adapted (tree-dwelling) primitive catarrhines from East Africa suggest a long history of prior diversification.

Among the genera thought to be in the ape lineage leading up to 13 million years ago are Proconsul, Rangwapithecus, Dendropithecus, Limnopithecus, Nacholapithecus, Equatorius, Nyanzapithecus, Afropithecus, Heliopithecus, and Kenyapithecus, all from East Africa.

Molecular evidence indicates that the lineage of gibbons diverged from the line of great apes some 18–12 mya, and that of orangutans (subfamily Ponginae)[b] diverged from the other great apes at about 12 million years; there are no fossils that clearly document the ancestry of gibbons, which may have originated in a so-far-unknown Southeast Asian hominoid population, but fossil proto-orangutans may be represented by Sivapithecus from India and Griphopithecus from Turkey, dated to around 10 mya.

The fossil record, however, of gorillas and chimpanzees is limited; both poor preservation – rain forest soils tend to be acidic and dissolve bone – and sampling bias probably contribute to this problem.

The species evolved in South and East Africa in the Late Pliocene or Early Pleistocene, 2.5–2 Ma, when it diverged from the australopithecines with the development of smaller molars and larger brains.

[82] Earlier evidence from sequencing mitochondrial DNA suggested that no significant gene flow occurred between H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens, and that the two were separate species that shared a common ancestor about 660,000 years ago.

[94] In 2008, archaeologists working at the site of Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia uncovered a small bone fragment from the fifth finger of a juvenile member of another human species, the Denisovans.

Corinne Simoneti at Vanderbilt University, in Nashville and her team have found from medical records of 28,000 people of European descent that the presence of Neanderthal DNA segments may be associated with a higher rate of depression.

Since Homo sapiens separated from its last common ancestor shared with chimpanzees, human evolution is characterized by a number of morphological, developmental, physiological, behavioral, and environmental changes.

It is possible that bipedalism was favored because it freed the hands for reaching and carrying food, saved energy during locomotion,[123] enabled long-distance running and hunting, provided an enhanced field of vision, and helped avoid hyperthermia by reducing the surface area exposed to direct sun; features all advantageous for thriving in the new savanna and woodland environment created as a result of the East African Rift Valley uplift versus the previous closed forest habitat.

[130] The most significant changes occurred in the pelvic region, where the long downward facing iliac blade was shortened and widened as a requirement for keeping the center of gravity stable while walking;[28] bipedal hominids have a shorter but broader, bowl-like pelvis due to this.

[134] Delayed human sexual maturity also led to the evolution of menopause with one explanation, the grandmother hypothesis, providing that elderly women could better pass on their genes by taking care of their daughter's offspring, as compared to having more children of their own.

[177] The ulnar opposition—the contact between the thumb and the tip of the little finger of the same hand—is unique to the genus Homo,[178] including Neanderthals, the Sima de los Huesos hominins and anatomically modern humans.

A number of other changes have also characterized the evolution of humans, among them an increased reliance on vision rather than smell (highly reduced olfactory bulb); a longer juvenile developmental period and higher infant dependency;[181] a smaller gut and small, misaligned teeth; faster basal metabolism;[182] loss of body hair;[183] an increase in eccrine sweat gland density that is ten times higher than any other catarrhinian primates,[184] yet humans use 30% to 50% less water per day compared to chimps and gorillas;[185] more REM sleep but less sleep in total;[186] a change in the shape of the dental arcade from u-shaped to parabolic; development of a chin (found in Homo sapiens alone); styloid processes; and a descended larynx.

For another example, the population at risk of the severe debilitating disease kuru has significant over-representation of an immune variant of the prion protein gene G127V versus non-immune alleles.

Many of Darwin's early supporters (such as Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Lyell) did not initially agree that the origin of the mental capacities and the moral sensibilities of humans could be explained by natural selection, though this later changed.

)[231] The Afar Triangle area would later yield discovery of many more hominin fossils, particularly those uncovered or described by teams headed by Tim D. White in the 1990s, including Ardipithecus ramidus and A. kadabba.

On the basis of a separation from the orangutan between 10 and 20 million years ago, earlier studies of the molecular clock suggested that there were about 76 mutations per generation that were not inherited by human children from their parents; this evidence supported the divergence time between hominins and chimpanzees noted above.

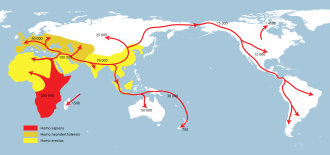

The multiregional hypothesis proposed that the genus Homo contained only a single interconnected population as it does today (not separate species), and that its evolution took place worldwide continuously over the last couple of million years.

[249][250] Sequencing mtDNA and Y-DNA sampled from a wide range of indigenous populations revealed ancestral information relating to both male and female genetic heritage, and strengthened the "out of Africa" theory and weakened the views of multiregional evolutionism.

[258] Studies of the human genome using machine learning have identified additional genetic contributions in Eurasians from an "unknown" ancestral population potentially related to the Neanderthal-Denisovan lineage.

In this theory, there was a coastal dispersal of modern humans from the Horn of Africa crossing the Bab el Mandib to Yemen at a lower sea level around 70,000 years ago.

[199] Recent genetic evidence suggests that all modern non-African populations, including those of Eurasia and Oceania, are descended from a single wave that left Africa between 65,000 and 50,000 years ago.

The main source of knowledge about the evolutionary process has traditionally been the fossil record, but since the development of genetics beginning in the 1970s, DNA analysis has come to occupy a place of comparable importance.

By comparing the parts of the genome that are not under natural selection and which therefore accumulate mutations at a fairly steady rate, it is possible to reconstruct a genetic tree incorporating the entire human species since the last shared ancestor.

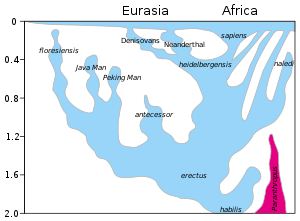

From these early species, the australopithecines arose around 4 million years ago and diverged into robust (also called Paranthropus) and gracile branches, one of which (possibly A. garhi) probably went on to become ancestors of the genus Homo.

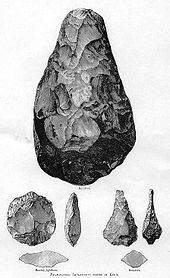

[193][291][292][293] The period from 700,000 to 300,000 years ago is also known as the Acheulean, when H. ergaster (or erectus) made large stone hand axes out of flint and quartzite, at first quite rough (Early Acheulian), later "retouched" by additional, more-subtle strikes at the sides of the flakes.

* Mya – million years ago, kya – thousand years ago