Anti-art

[2] The term is associated with the Dada movement and is generally accepted as attributable [citation needed] to Marcel Duchamp pre-World War I around 1914, when he began to use found objects as art.

[3][4] An expression of anti-art may or may not take traditional form or meet the criteria for being defined as a work of art according to conventional standards.

[11] Anti-art artworks may articulate a disagreement with the generally supposed notion of there being a separation between art and life.

Examples of this sort of phenomenon might include monochrome paintings, empty frames, silence as music, chance art.

Anti-art is also often seen to make use of highly innovative materials and techniques, and well beyond—to include hitherto unheard of elements in visual art.

Holding a strong anti-essentialist position he states also that art has not always existed and is not universal but peculiar to Europe.

Founded by Jules Lévy in 1882, the Incoherents organized charitable art exhibitions intended to be satirical and humoristic, they presented "...drawings by people who can't draw..."[26] and held masked balls with artistic themes, all in the greater tradition of Montmartre cabaret culture.

[27] In their commitment to satire, irreverence and ridicule they produced a number of works that show remarkable formal similarities to creations of the avant-garde of the 20th century: ready-mades,[28] monochromes,[29] empty frames[30] and silence as music.

[31] Beginning in Switzerland, during World War I, much of Dada, and some aspects of the art movements it inspired, such as Neo-Dada, Nouveau réalisme,[32] and Fluxus, is considered anti-art.

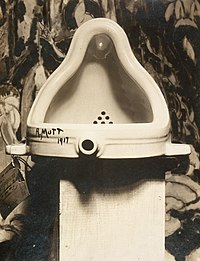

[38] Beginning in 1913 Marcel Duchamp's readymades challenged individual creativity and redefined art as a nominal rather than an intrinsic object.

"[41] In addition, Tzara, who once stated that "logic is always false",[42] probably approved of Walter Serner's vision of a "final dissolution".

[43] A core concept in Tzara's thought was that "as long as we do things the way we think we once did them we will be unable to achieve any kind of livable society.

"[44] Originating in Russia in 1919, constructivism rejected art in its entirety and as a specific activity creating a universal aesthetic[45] in favour of practices directed towards social purposes, "useful" to everyday life, such as graphic design, advertising and photography.

[49][50][51] Breton and his comrades supported Leon Trotsky and his International Left Opposition for a while, though there was an openness to anarchism that manifested more fully after World War II.

Breton believed the tenets of Surrealism could be applied in any circumstance of life, and is not merely restricted to the artistic realm.

In 1929, Breton asked Surrealists to assess their "degree of moral competence", and theoretical refinements included in the second manifeste du surréalisme excluded anyone reluctant to commit to collective action[53] By the end of World War II the surrealist group led by André Breton decided to explicitly embrace anarchism.

The most radical of the Letterist films, Wolman's The Anticoncept and Debord's Howlings for Sade abandoned images altogether.

In 1956, recalling the infinitesimals of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, quantities which could not actually exist except conceptually, the founder of Lettrism, Isidore Isou, developed the notion of a work of art which, by its very nature, could never be created in reality, but which could nevertheless provide aesthetic rewards by being contemplated intellectually.

In its simplest form, this might involve nothing more than the inclusion of several blank pages in a book, for the reader to add his or her own contributions.

The freeing up of gesture was another legacy of L'Art Informel, and the members of Group Kyushu took to it with great verve, throwing, dripping, and breaking material, sometimes destroying the work in the process.

Beginning in the 1950s in France, the Letterist International and after the Situationist International developed a dialectical viewpoint, seeing their task as superseding art, abolishing the notion of art as a separate, specialized activity and transforming it so it became part of the fabric of everyday life.

[6] The members of the Situationist International liked to think they were probably the most radical,[6][57] politicized,[6] well organized, and theoretically productive anti-art movement, reaching their apex with the student protests and general strike of May 1968 in France, a view endorsed by others including the academic Martin Puchner.

[6] In 1959 Giuseppe Pinot-Gallizio proposed Industrial Painting as an "industrial-inflationist art"[58] Similar to Dada, in the 1960s, Fluxus included a strong current of anti-commercialism and an anti-art sensibility, disparaging the conventional market-driven art world in favor of an artist-centered creative practice.

[61] Flynt wanted avant-garde art to become superseded by the terms of veramusement and brend – neologisms meaning approximately pure recreation.

[62] Maciunas strived to uphold his stated aims of demonstrating the artist's 'non-professional status...his dispensability and inclusiveness' and that 'anything can be art and anyone can do it.

According to the philosopher Roger Taylor the concept of art is not universal but is an invention of bourgeois ideology helping to promote this social order.

Unlike earlier art-strike proposals such as that of Gustav Metzger in the 1970s, it was not intended as an opportunity for artists to seize control of the means of distributing their own work, but rather as an exercise in propaganda and psychic warfare aimed at smashing the entire art world rather than just the gallery system.

Most notoriously, when their plans to use banknotes as part of a work of art fell through, they burnt a million pounds in cash.