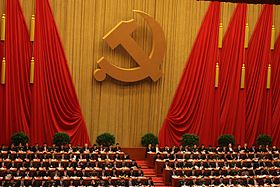

Anti-corruption campaign under Xi Jinping

The campaign, carried out under the aegis of Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, was the largest organized anti-corruption effort in the history of CCP rule in China.

[11][better source needed] The proposed constitutional changes published on February 25 envision the creation of a new anti-graft state agency that merges the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection and various anti-corruption government departments.

The types of offenses vary, though usually they involve trading bribes for political favours, such as local businesses trying to secure large government contracts or subordinates seeking promotions for higher office.

[18][better source needed] Meanwhile, in the latter half of 2013, a separate operation began to investigate officials with connections to Zhou Yongkang, former Politburo Standing Committee member and national security chief.

These teams were sent to the provinces of Shanxi, Jilin, Yunnan, Anhui, Hunan and Guangdong, as well as the Xinhua News Agency, the Ministry of Commerce, and the state-owned company overseeing the construction of the Three Gorges Dam.

Between 23 and 29 August 2014, four sitting members of the province's top governing council, the provincial Party Standing Committee, were sacked in quick succession, giving rise to what became known as the "great Shanxi political earthquake".

[24][better source needed] As the public awaited word on the fate of Zhou Yongkang amid intense rumours circulating inside the country and in international media, on 30 June, an announcement came from Beijing that General Xu Caihou, former member of the Politburo and vice chairman of the Central Military Commission from 2004 to 2013, was being expelled from the party for taking bribes in exchange for promotions, and facing criminal prosecution.

The official confirmation that Zhou was under investigation made him the first Politburo Standing Committee member to fall from grace since the end of the Cultural Revolution, and broke the unspoken rule of "PSC criminal immunity" that has been the norm for over three decades.

The internal investigation concluded that Zhou abused his power, maintained extramarital affairs with multiple women, took massive bribes, exchanged money and favours for sex, and "leaked state and party secrets.

[29][better source needed] On 22 December 2014, Ling Jihua, former senior aide to former Party general secretary Hu Jintao and a political star whose ambitions were quashed by the untimely death of his Ferrari-driving son, also fell under the anti-graft dragnet.

Ling was serving as the head of the party's United Front Work Department at the time, and also was vice chairman of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), a legislative advisory body.

The inspection teams in the province uncovered widespread collusion between those who hold political power and the "coal bosses" that stack their wallets in exchange for favourable treatment in approving development projects.

Wan Qingliang, the popular and relatively youthful party chief of Guangzhou known for his frugality and accessibility, was sacked in the third quarter of 2014, and was also replaced by an outsider, former Tianjin vice mayor Ren Xuefeng.

[38][better source needed] In Jiangsu, home province of former party leader Jiang Zemin and disgraced security chief Zhou Yongkang, several 'native sons' with seemingly promising political futures underwent investigation.

"[44] In 2014, the British news magazine The Economist wrote in its "Banyan" column, "it is hard not to see corruption allegations as the latter-day weapon of choice in the winner-takes-all power struggles that the party has always suffered".

[45] Meanwhile, He Pin, editor at overseas Chinese news portal Boxun, likened Zhou Yongkang, Bo Xilai, Ling Jihua, and Xu Caihou, to a latter-day "Gang of Four", whose real crime was not corruption but conspiring to usurp power.

[46] Chinese writer Murong Xuecun, a continual critic of the CCP, wrote in an opinion article "In my view, Xi's anti-corruption campaign looks more like a Stalinist political purge... he relies on the regulations of the party and not on the laws of the state, the people carrying it out operate like the KGB, and most cases cannot be reported on with any transparency.

Li Weidong, former editor of the Reform magazine in China, told Voice of America that by signalling that no one is off limits and by targeting retired officials, the campaign aimed to reduce the undue influence of party "elders" who were no longer in office but nevertheless wanted to interfere in political affairs.

Writing for Radio Free Asia, Liu Qing, among others, suggest that the campaign's main aim was to extinguish vestiges of influence of former Party general secretary Jiang Zemin.

Proponents of this view believe that the ultimate aim of the campaign is to strengthen the role of institutions and stamp out factionalism and networks of personal loyalty, thereby creating a more united and meritocratic organization and achieving greater efficiency for governance.

Duowei wrote that the campaign is part of a wider agenda of systemic reform aimed at restoring legitimacy of the CCP's mandate to rule, which – in the decades immediately prior – was heavily challenged by widespread corruption, a widening gap between rich and poor, social injustice, and excessive focus on material wealth.

In this view, the campaign is consistent to the other initiatives focused on social justice undertaken by Xi, including pushing ahead legal reform, abolishing re-education through labour, and castigating local officials from meddling in judicial proceedings.

[55] Li believes that not only has Xi's campaign had the effect of truly curbing corrupt practices at all levels of government, it has also restored public confidence in the CCP's mandate to rule, and has also returned massive ill-gotten gains back into state coffers which could be re-directed towards economic development.

For example, by tackling graft in state-owned enterprises, seen as bastions of entitlement, entrenched vested interests, and glaring inefficiencies, the government is better able to pursue economic reform programs aimed at liberalizing markets, breaking up monopolies, and reducing state control.

[54] Academic Keyu Jin writes that though there may be political motivations behind the campaign, its scope, depth, and sustained effort "proves the seriousness of the intention to sever corrosive links fostered in an era of rapid but disorderly growth.

[58] Outside observers have noted that crackdowns on graft inside of the PLA are motivated at least in part by a desire to increase military readiness after viewing the effects of corruption on the Russian armed forces during the invasion of Ukraine.

[61] Conversely, state media and some observers have pointed out that the CCDI has undergone significant structural reform in recent years aimed at making anti-corruption efforts more depoliticized, rules-based, and process-oriented.

Upon Xi's assuming the party leadership, further reforms were enacted to make the CCDI a bona fide control and auditing organization governed by a sophisticated set of rules and regulations to ensure professionalism and procedural fairness.

Earlier on, domestic and international observers commented on the possibility that the campaign is an emblematic feature of Chinese political culture which has, since its imperial days, invariably attempted tackling corruption in a high-profile manner when a new leader comes to power.

[69][70] In her 2023 book The Blind Eye (Danish: Det Blinde Øje), which examines the 2020 mink cull in Denmark, author Mathilde Walter Clark [da] links the decline in global fur prices after 2013 directly to Xi's campaign, arguing that the arrest of several key customers, crackdowns on illegal zero-tariff smuggling to China via Hong Kong, and a more cautious approach by Chinese elites towards projecting wealth were pivotal to the decline.