Antillia

Antillia (or Antilia) is a phantom island that was reputed, during the 15th-century age of exploration, to lie in the Atlantic Ocean, far to the west of Portugal and Spain.

The island also went by the name of Isle of Seven Cities (Ilha das Sete Cidades in Portuguese, Isla de las Siete Ciudades in Spanish).

Seeking to flee from the Muslim conquerors, seven Christian Visigothic bishops embarked with their flocks on ships and set sail westwards into the Atlantic Ocean, eventually landing on an island (Antillia) where they founded seven settlements.

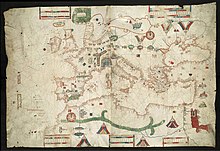

The routine appearance of such a large "Antillia" in 15th-century nautical charts has led to speculation that it might represent the American landmass,[1] and has fueled many theories of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact.

[4] The peoples of the Iberian Peninsula, who were closest to the real Atlantic islands of the Canaries, Madeira and Azores, and whose seafarers and fishermen may have seen and even visited them,[5] articulated their own tales.

The principal source is an inscription on Martin Behaim's 1492 Nuremberg globe which reads (in English translation): In the year 734 after the birth of Christ, when all Spain was overrun by the miscreants of Africa, this Island of Antillia, called also the Isle of the Seven Cities, was peopled by the Archbishop of Porto with six other bishops, and certain companions, male and female, who fled from Spain with their cattle and property.

[15] Medina gives the island's dimensions as 87 leagues in length and 28 in width, with "many good ports and rivers", and says it is situated on the latitude of the Straits of Gibraltar, that sailors have seen it from a distance, but disappears when they approach it.

Besieged by the Muslim armies and finding his situation hopeless, Sacaru negotiated capitulation, and proceeded, with all who wished to follow him, to embark on a fleet for exile in the Canary islands.

[21] It is mentioned again in a royal letter (dated 24 July 1486), issued by King John II of Portugal at the request of Fernão Dulmo authorizing him to search for and "discover the island of Seven Cities".

Some suggest the ante-ilha etymology might be older, possibly related in meaning to the "Aprositus" ("the Inaccessible"), the name reported by Ptolemy for one of the Fortunate Isles.

[25] Others regard the "ante-ilha" etymology as unsatisfactory, on the basis that "ante", in geographical usage, suggests it sits opposite another island, not a continent.

[citation needed] With the existence of lands out in the Atlantic Ocean confirmed, 14th-century European geographers began plumbing the old legends and plotting and naming many of these mythical islands on their nautical charts, alongside the new discoveries.

They are commonly referred to collectively as the "Antillia group" or (to use Beccario's label) the insulae de novo rep(er)te ("islands newly reported").

It appears in virtually all of the known surviving Portolan charts of the Atlantic – notably those of the Genoese B. Beccario or Beccaria (1435), the Venetian Andrea Bianco (1436), and Grazioso Benincasa (1476 and 1482).

The form of the island occasionally becomes more figurative than the semi-abstract representations of Bartolomeo de Pareto, Benincasa and others: Bianco, for instance, shifts its orientation to northwest–southeast, transmutes generic bays into river mouths (including a large one on the northeastern coast), and elongates a southern tail into a cape with a small cluster of islets offshore.

Each congregation founded a city, namely, Aira, Anhuib, Ansalli, Ansesseli, Ansodi, Ansolli and Con,[42] and once established, burnt their caravel ships as a symbol of their autonomy.

[44] Since these events predated the Kingdom of Portugal and the clergy's heritage marked a claim to significant strategical gains, Spain counterclaimed that the expedition was, in fact, theirs.

[citation needed] With this legend underpinning the growing reports of a bountiful civilisation midway between Europe and Cipangu, or Japan,[46] the quest to discover the Seven Cities attracted significant attention.

However, by the last decade of the 15th century, the Portuguese state's official sponsorship of such exploratory voyages had ended,[47] and in 1492, under the Spanish flag of Ferdinand and Isabella, Christopher Columbus set out on his historic journey to Asia, citing the island as the perfect halfway house by the authority of Paul Toscanelli.

Upon Cabot's return to England, two residents of Bristol – the Italian merchant Raimondo de Soncino (in a letter to the Duke of Milan, dated August 24, 1497) and Bristol merchant John Day (in a letter to Christopher Columbus, written c. December 1497) – refer to Cabot making landfall and coasting the "Island of Seven Cities".

Others following d'Anghiera suggested contenders in the West Indies for Antillia's heritage (most often either Puerto Rico or Trinidad), and as a result the Caribbean islands became known as the Antilles.