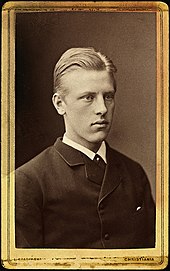

Fridtjof Nansen

Although he retired from exploration after his return to Norway, his techniques of polar travel and his innovations in equipment and clothing influenced a generation of subsequent Arctic and Antarctic expeditions.

[9] Nansen's sporting prowess continued to develop; at 18 he broke the world one-mile (1.6 km) skating record, and in the following year won the national cross-country skiing championship, a feat he would repeat on 11 subsequent occasions.

He was to spend the next six years of his life there—apart from a six-month sabbatical tour of Europe—working and studying with leading figures such as Gerhard Armauer Hansen, the discoverer of the leprosy bacillus,[15] and Daniel Cornelius Danielssen, the museum's director who had turned it from a backwater collection into a centre of scientific research and education.

[16] Nansen's chosen area of study was the then relatively unexplored field of neuroanatomy, specifically the central nervous system of lower marine creatures.

Before leaving for his sabbatical in February 1886 he published a paper summarising his research to date, in which he stated that "anastomoses or unions between the different ganglion cells" could not be demonstrated with certainty.

[21] These plans received a generally poor reception in the press;[22] one critic had no doubt that "if [the] scheme be attempted in its present form ... the chances are ten to one that he will ... uselessly throw his own and perhaps others' lives away".

The project was eventually launched with a donation from a Danish businessman, Augustin Gamél; the rest came mainly from small contributions from Nansen's countrymen, through a fundraising effort organised by students at the university.

[39] Nansen's main task in the following weeks was writing his account of the expedition, but he found time late in June to visit London, where he met the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII), and addressed a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS).

[39] The RGS president, Sir Mountstuart Elphinstone Grant Duff, said that Nansen had claimed "the foremost place amongst northern travellers", and later awarded him the Society's prestigious Patron's Medal.

This ship would enter the ice pack close to the approximate location of Jeannette's sinking, drifting west with the current towards the pole and beyond it—eventually reaching the sea between Greenland and Spitsbergen.

[59] As the ship's northerly progress continued at a rate rarely above a kilometre and a half per day, Nansen began privately to consider a new plan—a dog sledge journey towards the pole.

[81] It was the British explorer Frederick Jackson, who was leading an expedition to Franz Josef Land and was camped at Cape Flora on nearby Northbrook Island.

Tributes arrived from all over the world; typical was that from the British mountaineer Edward Whymper, who wrote that Nansen had made "almost as great an advance as has been accomplished by all other voyages in the nineteenth century put together".

In 1897 he accepted a professorship in zoology at the Royal Frederick University,[91] which gave him a base from which he could tackle the major task of editing the reports of the scientific results of the Fram expedition.

[93] Through his connection with the latter body, in the summer of 1900 Nansen embarked on his first visit to Arctic waters since the Fram expedition, a cruise to Iceland and Jan Mayen Land on the oceanographic research vessel Michael Sars, named after Eva's father.

[97] Although Nansen refused to meet his own countryman and fellow-explorer Carsten Borchgrevink (whom he considered a fraud),[98] he gave advice to Robert Falcon Scott on polar equipment and transport, prior to the 1901–04 Discovery expedition.

[106] However, at Michelsen's request he went to Berlin and then to London where, in a letter to The Times, he presented Norway's legal case for a separate consular service to the English-speaking world.

[103] This was held on 13 August 1905 and resulted in an overwhelming vote for independence, at which point King Oscar relinquished the crown of Norway while retaining the Swedish throne.

[115] In 1909 Nansen combined with Bjørn Helland-Hansen to publish an academic paper, The Norwegian Sea: its Physical Oceanography, based on the Michael Sars voyage of 1900.

[116] Nansen had by now retired from polar exploration, the decisive step being his release of Fram to fellow Norwegian Roald Amundsen, who was planning a North Pole expedition.

[122] At the request of the Royal Geographical Society, Nansen began work on a study of Arctic discoveries, which developed into a two-volume history of the exploration of the northern regions up to the beginning of the 16th century.

[125] His personal life was troubled around this time; in January 1913 he received news of the suicide of Hjalmar Johansen, who had returned in disgrace from Amundsen's successful South Pole expedition.

[121] In the summer of 1913, Nansen travelled to the Kara Sea, by the invitation of Jonas Lied, as part of a delegation investigating a possible trade route between Western Europe and the Siberian interior.

In paying tribute to his work, the responsible committee recorded that the story of his efforts "would contain tales of heroic endeavour worthy of those in the accounts of the crossing of Greenland and the great Arctic voyage.

[154] He supported a settlement of the post-war reparations issue and championed Germany's membership of the League, which was granted in September 1926 after intensive preparatory work by Nansen.

[158] Two years later Nansen broadcast a memorial oration to Amundsen, who had disappeared in the Arctic while organising a rescue party for Nobile whose airship had crashed during a second polar voyage.

At the inaugural rally of the League in Oslo (as Christiania had now been renamed), Nansen declared: "To talk of the right of revolution in a society with full civil liberty, universal suffrage, equal treatment for everyone ... [is] idiotic nonsense.

[170] Among the many tributes paid to him subsequently was that of Lord Robert Cecil, a fellow League of Nations delegate, who spoke of the range of Nansen's work, done with no regard for his own interests or health: "Every good cause had his support.

As a young man he embraced the revolution in skiing methods that transformed it from a means of winter travel to a universal sport, and quickly became one of Norway's leading skiers.

His Polhøgda mansion is now home to the Fridtjof Nansen Institute, an independent foundation which engages in research on environmental, energy and resource management politics.