Antiphellus

During the Roman period, Antiphellus received funds from the civic benefactor Opramoas of Rhodiapolis that may have been used to help rebuild the city following the earthquake that devastated the region in 141.

The restored Hellenistic amphitheatre at Antiphellus, originally built to seat 4000 spectators, and still largely complete, never possessed a permanent stone stage.

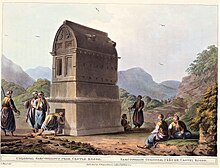

Surviving ruins visible on the ground include the 4th century BCE Doric Tomb, which has a 1.9 metres (6 ft 3 in) high entrance and a chamber decorated with a relief of dancing girls; the King's Tomb, located in the centre of the modern town, which has a uniquely written and as yet untranslated Lycian inscription; a small 1st century BCE temple; rock tombs set in cliffs above the modern town; and parts of the city's ancient sea wall.

The original Lycian name for Antiphellus (Ancient Greek: "the land opposite the rocks") was Habesos;[1][2] according to the Roman military commander Pliny the Elder, the city's pre-Hellenic name was Habessus.

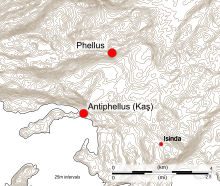

[1] Located at the head of a bay on the region's southern coast, the settlement served during the Hellenic period as the port of the nearby inland city of Phellus,[4] although despite the vulnerability of its coastal position, neither a defensive wall or an acropolis was ever built there.

[11] The shock from this earthquake triggered a tsunami that inundated the Lycian coast and travelled a considerable distance inland.

He also attended the provincial synod held in 458 in connection with the murder of Proterius of Alexandria, but because of health difficulties with his hands, the acts of the meeting were signed on his behalf by the priest Eustathius.

He gave a description of what he found there, including the amphitheatre and groups of inscribed and plain sarcophagi, noting that the inscriptions he saw were: "from the rudeness of their execution, to be very antient.

[20] In 1841, he produced drawings of specimens of ends of sarcophagi, pediments, and doors of tombs, and Thomas Abel Brimage Spratt's Travels in Lycia, Milyas, and the Cibyratis (1847) contains a plan of the ancient city's ruins.

[22] Much of the archaeology at Antiphellus has been lost due to the urban development of Kaş;[23] Fellows observed that the settlement had expanded even since his previous visit and had swallowed up many of the ruins.

[24] Excavations carried out in the modern town in 1952 produced few results, leading the archaeological team to conclude that 4th century Antiphellus consisted of a few buildings, concentrated near the harbour.

[11] The retaining wall of the amphitheatre, which curves around in slightly more than a semicircle, is built of irregular ashlar blocks, which vary in size and shape.

[28] One of the town's sarcophagi is the 4th century BCE Lycian Inscribed Mausoleum, known locally as the King's Tomb, which is located on Uzunçarşı Street.

[30] On the hyposorium is an unusual type of Lycian epitaph, being in the form of a poem, as observed by Fellows in the 1840s, who wrote that "the inscription does not begin in the manner of any of those we have yet met with, nor does it contain any words of a funereal character".

[42] The harbour lay on the seaward side of the isthmus, where a reef runs out to sea, providing protection; it may have been strengthened in ancient times.

The part of the ashlar sea-wall that survives to the west of the modern town stands six courses high for a length of over 500 yards (460 m).