Anti-reflective coating

In complex systems such as cameras, binoculars, telescopes, and microscopes the reduction in reflections also improves the contrast of the image by elimination of stray light.

Many coatings consist of transparent thin film structures with alternating layers of contrasting refractive index.

Many anti-reflection lenses include an additional coating that repels water and grease, making them easier to keep clean.

Antireflective coatings (ARC) are often used in microelectronic photolithography to help reduce image distortions associated with reflections off the surface of the substrate.

Different types of antireflective coatings are applied either before (Bottom ARC, or BARC) or after the photoresist, and help reduce standing waves, thin-film interference, and specular reflections.

The optical glass available at the time tended to develop a tarnish on its surface with age, due to chemical reactions with the environment.

The closest materials with good physical properties for a coating are magnesium fluoride, MgF2 (with an index of 1.38), and fluoropolymers, which can have indices as low as 1.30, but are more difficult to apply.

Researchers have produced films of mesoporous silica nanoparticles with refractive indices as low as 1.12, which function as antireflection coatings.

Coatings that give very low reflectivity over a broad band of frequencies can also be made, although these are complex and relatively expensive.

Optical coatings can also be made with special characteristics, such as near-zero reflectance at multiple wavelengths, or optimal performance at angles of incidence other than 0°.

Absorbing ARCs often make use of unusual optical properties exhibited in compound thin films produced by sputter deposition.

Moths' eyes have an unusual property: their surfaces are covered with a natural nanostructured film, which eliminates reflections.

Canon uses the moth-eye technique in their SWC subwavelength structure coating, which significantly reduces lens flare.

Thin-film effects arise when the thickness of the coating is approximately the same as a quarter or a half a wavelength of light.

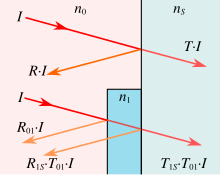

The strength of the reflection depends on the ratio of the refractive indices of the two media, as well as the angle of the surface to the beam of light.

For the simplified scenario of visible light travelling from air (n0 ≈ 1.0) into common glass (nS ≈ 1.5), the value of R is 0.04, or 4%, on a single reflection.

The use of an intermediate layer to form an anti-reflection coating can be thought of as analogous to the technique of impedance matching of electrical signals.

(A similar method is used in fibre optic research, where an index-matching oil is sometimes used to temporarily defeat total internal reflection so that light may be coupled into or out of a fiber.)

), however the anti-reflective performance is worse in this case due to the stronger dependence of the reflectance on wavelength and the angle of incidence.

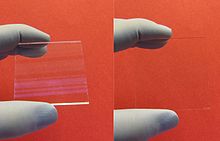

Real coatings do not reach perfect performance, though they are capable of reducing a surface reflection coefficient to less than 0.1%.

Other difficulties include finding suitable materials for use on ordinary glass, since few useful substances have the required refractive index (n ≈ 1.23) that will make both reflected rays exactly equal in intensity.

Magnesium fluoride (MgF2) is often used, since this is hard-wearing and can be easily applied to substrates using physical vapor deposition, even though its index is higher than desirable (n = 1.38).

Further reduction is possible by using multiple coating layers, designed such that reflections from the surfaces undergo maximal destructive interference.

By using two or more layers, each of a material chosen to give the best possible match of the desired refractive index and dispersion, broadband anti-reflection coatings covering the visible range (400–700 nm) with maximal reflectivity of less than 0.5% are commonly achievable.

If the coated optic is used at non-normal incidence (that is, with light rays not perpendicular to the surface), the anti-reflection capabilities are degraded somewhat.

Harold Dennis Taylor of Cooke company developed a chemical method for producing such coatings in 1904.

[24][25] Interference-based coatings were invented and developed in 1935 by Olexander Smakula, who was working for the Carl Zeiss optics company.

[29][30] Katharine Burr Blodgett and Irving Langmuir developed organic anti-reflection coatings known as Langmuir–Blodgett films in the late 1930s.