Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

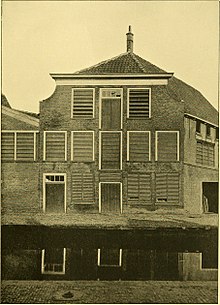

Raised in Delft, Dutch Republic, Van Leeuwenhoek worked as a draper in his youth and founded his own shop in 1654.

Using single-lensed microscopes of his own design and make, Van Leeuwenhoek was the first to observe and to experiment with microbes, which he originally referred to as dierkens, diertgens or diertjes.

[13][14] In July 1654, Van Leeuwenhoek married Barbara de Mey in Delft, with whom he fathered one surviving daughter, Maria (four other children died in infancy).

In 1669 he was appointed as a land surveyor by the court of Holland; at some time he combined it with another municipal job, being the official "wine-gauger" of Delft and in charge of the city wine imports and taxation.

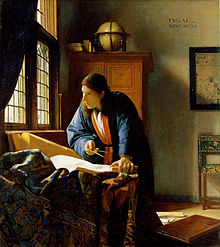

[17] Van Leeuwenhoek was a contemporary of another famous Delft citizen, the painter Johannes Vermeer, who was baptized just four days earlier.

It has been suggested that he is the man portrayed in two Vermeer paintings of the late 1660s, The Astronomer and The Geographer, but others argue that there appears to be little physical similarity.

Significantly, a May 2021 neutron tomography study of a high-magnification Leeuwenhoek microscope[22] captured images of the short glass stem characteristic of this lens creation method.

[citation needed] After developing his method for creating powerful lenses and applying them to the study of the microscopic world,[24] Van Leeuwenhoek introduced his work to his friend, the prominent Dutch physician Reinier de Graaf.

In response, in 1673 the society published a letter from Van Leeuwenhoek that included his microscopic observations on mold, bees, and lice.

At first he had been reluctant to publicize his findings, regarding himself as a businessman with little scientific, artistic, or writing background, but de Graaf urged him to be more confident in his work.

[27] By the time Van Leeuwenhoek died in 1723, he had written some 190 letters to the Royal Society, detailing his findings in a wide variety of fields, centered on his work in microscopy.

[32] Antonie van Leeuwenhoek was elected to the Royal Society in February 1680 on the nomination of William Croone, a then-prominent physician.

[36] Around 1675, it was Johan Huydecoper, who was very interested in collecting and growing plants for his estate Goudestein, becoming in 1682 manager of the Hortus Botanicus Amsterdam.

[36] To the disappointment of his guests, Van Leeuwenhoek refused to reveal the cutting-edge microscopes he relied on for his discoveries, instead showing visitors a collection of average-quality lenses.

Stong used thin glass thread fusing instead of polishing, and successfully created some working samples of a Van Leeuwenhoek design microscope.

He studied a broad range of microscopic phenomena, and shared the resulting observations freely with groups such as the British Royal Society.

[49] Like Robert Boyle and Nicolaas Hartsoeker, Van Leeuwenhoek was interested in dried cochineal, trying to find out if the dye came from a berry or an insect.

[64][65][66][67] He studied rainwater, the seeds of oranges, worms in sheep's liver, the eye of a whale, the blood of fishes, mites, coccinellidae, the skin of elephants, Celandine, and Cinchona.

[49] By the end of his life, Van Leeuwenhoek had written approximately 560 letters to the Royal Society and other scientific institutions concerning his observations and discoveries.

[69] In 1981, the British microscopist Brian J. Ford found that Van Leeuwenhoek's original specimens had survived in the collections of the Royal Society of London.

[73] In Ford's opinion, Leeuwenhoek remained imperfectly understood, the popular view that his work was crude and undisciplined at odds with the evidence of conscientious and painstaking observation.

He constructed rational and repeatable experimental procedures and was willing to oppose received opinion, such as spontaneous generation, and he changed his mind in the light of evidence.

His experiments were ingenious, and he was "a scientist of the highest calibre", attacked by people who envied him or "scorned his unschooled origins", not helped by his secrecy about his methods.

[75] On 24 October 2016, Google commemorated the 384th anniversary of Van Leeuwenhoek's birth with a Doodle that depicted his discovery of "little animals" or animalcules, now known as unicellular organisms.