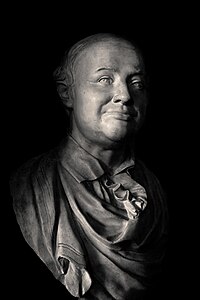

Mikhail Lomonosov

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov (/ˌlɒməˈnɒsɒf/;[1] Russian: Михаил Васильевич Ломоносов, IPA: [mʲɪxɐˈil vɐˈsʲilʲjɪvʲɪtɕ ləmɐˈnosəf] ⓘ; 19 November [O.S.

Lomonosov was born in the village of Mishaninskaya, later renamed Lomonosovo in his honor, in Archangelgorod Governorate, on an island not far from Kholmogory, in the far north of Russia.

[4] His father, Vasily Dorofeyevich Lomonosov, was a prosperous peasant fisherman turned ship owner, who amassed a small fortune transporting goods from Arkhangelsk to Pustozyorsk, Solovki, Kola, and Lapland.

[5] He remained at Denisovka until he was ten, when his father decided that he was old enough to participate in his business ventures, and Lomonosov began accompanying Vasily on trading missions.

When he was fourteen, Lomonosov was given copies of Meletius Smotrytsky's Modern Church Slavonic (a grammar book) and Leonty Magnitsky's Arithmetic.

Unhappy at home and intent on obtaining a higher education, which Lomonosov could not receive in Mishaninskaya, he was determined to leave the village.

[9] Shortly after arrival, he was admitted into the Slavic Greek Latin Academy by falsely claiming to be a son of a Kholmogory nobleman.

[11] Lomonosov lived on three kopecks a day, eating only black bread and kvass, but he made rapid progress scholastically.

[15] Lomonosov quickly mastered the German language, and in addition to philosophy, seriously studied chemistry, discovered the works of 17th century Irish theologian and natural philosopher Robert Boyle, and even began writing poetry.

[17] Lomonosov found it extremely difficult to maintain his growing family on the scanty and irregular allowance granted him by the Russian Academy of Sciences.

[18] Eager to improve Russia's educational system, in 1755, Lomonosov joined his patron Count Ivan Shuvalov in founding Moscow University.

He is widely and deservingly regarded as the "Father of Russian Science,"[20] though many of his scientific accomplishments were relatively unknown outside Russia until long after his death and gained proper appreciation only in late 19th and, especially, 20th centuries.

Anticipating the discoveries of Antoine Lavoisier, he wrote in his diary: "Today I made an experiment in hermetic glass vessels in order to determine whether the mass of metals increases from the action of pure heat.

The experiments – of which I append the record in 13 pages – demonstrated that the famous Robert Boyle was deluded, for without access of air from outside the mass of the burnt metal remains the same."

[15][25] At least in the English-speaking world, this attribution seems to have been owing to comments from the multi-lingual popular astronomy writer Willy Ley (1966), who consulted sources in both Russian and German, and wrote that Lomonosov observed a luminous ring (this was Ley's interpretation and was not indicated in quotes) and inferred from it the existence of an atmosphere "maybe greater than that of the Earth" (which was in quotes).

Because many modern transit observers have also seen a threadlike arc produced by refraction of sunlight in the atmosphere of Venus when the planet has progressed off the limb of the Sun, it has generally, if rather uncritically, been assumed that this was the same thing that Lomonosov saw.

[26] In 2012, Pasachoff and Sheehan[27] consulted original sources, and questioned the basis for the claim that Lomonosov observed the thin arc produced by the atmosphere of Venus.

A reference to the paper was even picked up by the Russian state-controlled media group RIA Novosti on 31 January 2013, under the headline "Astronomical Battle in US Over Lomonosov’s discovery."

An attempt was made by a group of researchers to experimentally reconstruct Lomonosov's observation using antique telescopes during the transit of Venus on 5–6 June 2012.

It should be kept in mind that, as stated in Sheehan and Westfall, "optical distortions at the interface between Venus and the Sun during transits are impressively large, and any inferences from them are fraught with peril".

[32] In 1759, with his collaborator, academician Joseph Adam Braun, Lomonosov was the first person to record the freezing of mercury and to carry out initial experiments with it.

[33] Believing that nature is subject to regular and continuous evolution, he demonstrated the organic origin of soil, peat, coal, petroleum and amber.

Lomonosov based his conceptions on the unity of the Earth's processes in time, and necessity to explain the planet's past from present.

Lomonosov got close to the theory of continental drift,[35] theoretically predicted the existence of Antarctica (he argued that icebergs of the Southern Ocean could be formed only on a dry land covered with ice),[36] and invented sea tools which made writing and calculating directions and distances easier.

In 1764, he organized an expedition (led by Admiral Vasili Chichagov) to find the Northeast Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans by sailing along the northern coast of Siberia.

In 1754, in his letter to Leonhard Euler, he wrote that his three years of experiments on the effects of chemistry of minerals on their colour led to his deep involvement in the mosaic art.

[40] Together with his contemporaries Alexander Sumarokov and Vasily Trediakovsky, Lomonosov sought the creation of a system of Russian linguistic conventions, syntax and prosody which would allow the advancement of a native literary tradition on the basis of Western European genres.

The iambic tetrameter and hexameter verse and the ten-line odic stanza which he developed had a lasting role in Russian poetry.

[40] According to A. Kahn, "the turgidity of the Lomonosovian ode derives from a propensity to create semantic clusters, usually through etymologic play or tropes, such as zeugma."

[citation needed] The street "Lomonosova iela" in the Maskavas Forštate district of Riga is named in honor of Lomonosov.