Appalachia

In the early 20th century, large-scale logging and coal mining firms brought jobs and modern amenities to Appalachia, but by the 1960s the region had failed to capitalize on any long-term benefits[8] from these two industries.

The TVA was responsible for the construction of hydroelectric dams that provide a vast amount of electricity and that support programs for better farming practices, regional planning, and economic development.

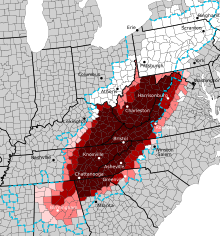

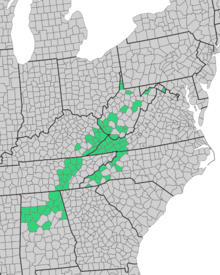

[6] The first major attempt to map Appalachia as a distinctive cultural region came in the 1890s with the efforts of Berea College president William Goodell Frost, whose "Appalachian America" included 194 counties in 8 states.

Sean Trende, senior elections analyst at RealClearPolitics, defines "Greater Appalachia" in his 2012 book, The Lost Majority, as including both the Appalachian Mountains region and the Upland South, following Protestant Scotch-Irish migrations to the southern and Midwestern United States in the 18th and 19th centuries.

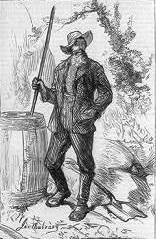

Attempts by President Rutherford B. Hayes to enforce the whiskey tax in the late 1870s led to an explosion in violence between Appalachian "moonshiners" and federal "revenuers" that lasted through the Prohibition period in the 1920s.

In an 1899 article in The Atlantic, Berea College president William G. Frost attempted to redefine the inhabitants of Appalachia as "noble mountaineers"—relics of the nation's pioneer period whose isolation had left them unaffected by modern times.

Several significant moments of investment by the United States government into areas of science and technology were established in the mid-20th century, notably with NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, crucial with the design of Apollo program launch vehicles and propulsion of the Space Shuttle program,[42] and at adjacent facilities Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the Y-12 National Security Complex in Oak Ridge, Tennessee with the Manhattan Project and advancements in supercomputing and nuclear power.

[58] The coal mining and manufacturing boom in the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought large numbers of Italians and Eastern Europeans to Appalachia, although most of these families left the region when the Great Depression shattered the economy in the 1930s.

Several 18th and 19th-century religious traditions are still practiced in parts of Appalachia, including natural water (or "creek") baptism, rhythmically chanted preaching, congregational shouting, snake handling, and foot washing.

While most church-goers in Appalachia attend fairly well-organized churches affiliated with regional or national bodies, small unaffiliated congregations are not uncommon in rural mountain areas.

Early education in the region evolved from teaching Christian morality and learning to read the Bible in small, one-room schoolhouses that convened in months when children were not needed to help with farm work.

African-American blues musicians played a significant role in developing the instrumental aspects of Appalachian music, most notably with the introduction of the five-stringed banjo—one of the region's iconic symbols—in the late 18th century.

In the years following World War I, British folklorist Cecil Sharp brought attention to Southern Appalachia when he noted that its inhabitants still sang hundreds of English and Scottish ballads that had been passed down to them from their ancestors.

Travellers' accounts published in 19th-century magazines gave rise to Appalachian local color, which reached its height with George Washington Harris's Sut Lovingood character of the 1860s and native novelists such as Mary Noailles Murfree.

Works such as Rebecca Harding Davis's Life in the Iron Mills (1861), Emma Bell Miles' The Spirit of the Mountains (1905), Catherine Marshall's Christy (1912), Horace Kephart's Our Southern Highlanders (1913) marked a shift in the region's literature from local color to realism.

[77] Along with the above-mentioned, some of Appalachia's best known writers include James Agee (A Death in the Family), Anne W. Armstrong (This Day and Time), Wendell Berry (Hannah Coulter, The Unforeseen Wilderness: An Essay on Kentucky's Red River Gorge, Selected Poems of Wendell Berry), Jesse Stuart (Taps for Private Tussie, The Thread That Runs So True), Denise Giardina (The Unquiet Earth, Storming Heaven), Lee Smith (Fair and Tender Ladies, On Agate Hill), Silas House (Clay's Quilt, A Parchment of Leaves), Wilma Dykeman (The Far Family, The Tall Woman), Keith Maillard (Alex Driving South, Light in the Company of Women, Hazard Zones, Gloria, Running, Morgantown, Lyndon Johnson and the Majorettes, Looking Good) Maurice Manning (Bucolics, A Companion for Owls), Anne Shelby (Appalachian Studies, We Keep a Store), George Ella Lyon (Borrowed Children, Don't You Remember?

), Pamela Duncan (Moon Women, The Big Beautiful), David Joy (Where All Light Tends to Go, The Weight of This World), Chris Offutt (No Heroes, The Good Brother), Charles Frazier (Cold Mountain, Thirteen Moons), Sharyn McCrumb (The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter), Robert Morgan (Gap Creek), Jim Wayne Miller (The Brier Poems), Gurney Norman (Divine Right's Trip, Kinfolks), Ron Rash (Serena), Elizabeth Madox Roberts (The Great Meadow, The Time of Man), Thomas Wolfe (Look Homeward Angel, You Can't Go Home Again), Rachel Carson (The Sea Around Us, Silent Spring; Presidential Medal of Freedom), and Jeannette Walls (The Glass Castle).

As told by Eastern Band Cherokee and western North Carolina storyteller Jerry Wolfe, these creatures include the chipmunk, also known as "seven stripes" from an angry bear scratching him down the back—four claw marks and the spaces in between making seven—and the copperhead who sneaks and thieves his way into becoming venomous.

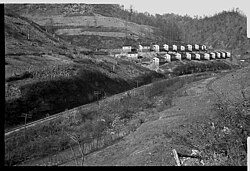

[92] In the late 19th century, the post-Civil War Industrial Revolution and the expansion of the nation's railroads brought a soaring demand for coal, and mining operations expanded rapidly across Appalachia.

Hundreds of thousands of workers poured into the region from across the United States and from overseas, essentially overhauling the cultural makeup of eastern Kentucky, West Virginia, and western Pennsylvania.

[citation needed] The manufacturing industry in Appalachia is rooted primarily in the ironworks and steelworks of early Pittsburgh and Birmingham, and in the textile mills that sprang up in North Carolina's Piedmont region in the mid-19th century.

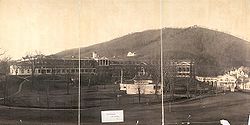

This economic shift led to a mass migration from small farms and rural areas to large urban centers, causing the populations of cities such as Birmingham, Knoxville, Tennessee, and Asheville, North Carolina, to swell exponentially.

However, difficulties paying retiree benefits, environmental struggles, and the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 led to a decline in the region's manufacturing operations.

[104] Important heritage tourism attractions in the region include the Biltmore Estate and the Eastern Band of the Cherokee reservation in North Carolina, Cades Cove in Tennessee, and Harpers Ferry in West Virginia.

The end of World War I (which opened up travel opportunities to Europe) and the arrival of the automobile (which changed the nation's vacation habits) led to the demise of all but a few of the region's spa resorts.

Millions of tons of rock were removed to build road segments such as Interstate 40 through the Pigeon River Gorge at the Tennessee-North Carolina state line and U.S. Route 23 in Letcher County, Kentucky.

The Blue Ridge Parkway's Linn Cove Viaduct, the construction of which required the assembly of 153 pre-cast segments 4,000 feet (1,200 m) up the slopes of Grandfather Mountain,[116] has been designated a historic civil engineering landmark.

[118] Ledford writes, "Always part of the mythical South, Appalachia continues to languish backstage in the American drama, still dressed, in the popular mind at least, in the garments of backwardness, violence, poverty, and hopelessness.

"[119] Otto argues that comic strips Li'l Abner by Al Capp and Barney Google by Billy DeBeck, which both began in 1934, caricatured the laziness and weakness for "corn squeezin's" (moonshine) of these "hillbillies".

The popular 1960s Andy Griffith Show and The Beverly Hillbillies on television and James Dickey's 1970 novel Deliverance perpetuated the stereotype, although the region itself underwent so many changes after 1945 that it scarcely resembles the comic images.