Aquifer

In 2013 large freshwater aquifers were discovered under continental shelves off Australia, China, North America and South Africa.

The reserves formed when ocean levels were lower and rainwater made its way into the ground in land areas that were not submerged until the ice age ended 20,000 years ago.

In mountainous areas (or near rivers in mountainous areas), the main aquifers are typically unconsolidated alluvium, composed of mostly horizontal layers of materials deposited by water processes (rivers and streams), which in cross-section (looking at a two-dimensional slice of the aquifer) appear to be layers of alternating coarse and fine materials.

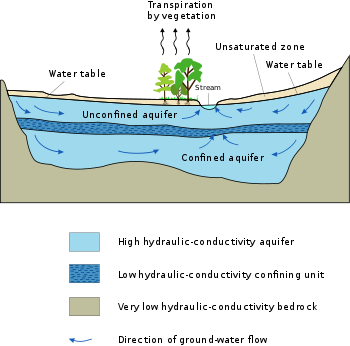

Since there are less fine-grained deposits near the source, this is a place where aquifers are often unconfined (sometimes called the forebay area), or in hydraulic communication with the land surface.

Typically (but not always) the shallowest aquifer at a given location is unconfined, meaning it does not have a confining layer (an aquitard or aquiclude) between it and the surface.

The term "perched" refers to ground water accumulating above a low-permeability unit or strata, such as a clay layer.

This term is generally used to refer to a small local area of ground water that occurs at an elevation higher than a regionally extensive aquifer.

Porous aquifer properties depend on the depositional sedimentary environment and later natural cementation of the sand grains.

Areas of the Deccan Traps (a basaltic lava) in west central India are good examples of rock formations with high porosity but low permeability, which makes them poor aquifers.

Similarly, the micro-porous (Upper Cretaceous) Chalk Group of south east England, although having a reasonably high porosity, has a low grain-to-grain permeability, with its good water-yielding characteristics mostly due to micro-fracturing and fissuring.

[15] Characterization of karst aquifers requires field exploration to locate sinkholes, swallets, sinking streams, and springs in addition to studying geologic maps.

These conventional investigation methods need to be supplemented with dye traces, measurement of spring discharges, and analysis of water chemistry.

[17] U.S. Geological Survey dye tracing has determined that conventional groundwater models that assume a uniform distribution of porosity are not applicable for karst aquifers.

[18] Linear alignment of surface features such as straight stream segments and sinkholes develop along fracture traces.

[19] Voids in karst aquifers can be large enough to cause destructive collapse or subsidence of the ground surface that can initiate a catastrophic release of contaminants.

For example, in the Barton Springs Edwards aquifer, dye traces measured the karst groundwater flow rates from 0.5 to 7 miles per day (0.8 to 11.3 km/d).

Aquifer depletion is a problem in some areas, especially in northern Africa, where one example is the Great Manmade River project of Libya.

However, new methods of groundwater management such as artificial recharge and injection of surface waters during seasonal wet periods has extended the life of many freshwater aquifers, especially in the United States.

[24] Saturated with water, they are confined beneath impermeable bitumen-saturated sands that are exploited to recover bitumen for synthetic crude oil production.

The BWS typically pose problems for the recovery of bitumen, whether by open-pit mining or by in situ methods such as steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD), and in some areas they are targets for waste-water injection.

[29] In the United States, the biggest users of water from aquifers include agricultural irrigation and oil and coal extraction.

[30] "Cumulative total groundwater depletion in the United States accelerated in the late 1940s and continued at an almost steady linear rate through the end of the century.

This carbonate aquifer has historically been providing high quality water for nearly 2 million people, and even today, is full because of tremendous recharge from a number of area streams, rivers and lakes.