Arabic literature

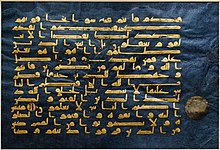

The other important genre of work in Qur'anic study is the tafsir or commentaries Arab writings relating to religion also includes many sermons and devotional pieces as well as the sayings of Ali which were collected in the 10th century as Nahj al-Balaghah or The Peak of Eloquence.

[5] Arabic literature at this time reverted to its state in al-Jahiliyyah, with markets such as Kinasa near Kufa and Mirbad [ar] near Basra, where poetry in praise and admonishment of political parties and tribes was recited.

Particularly from the beginning of the 12th century, with sponsorship from the Almoravid dynasty, the university played an important role in the development of literature in the region, welcoming scholars and writers from throughout the Maghreb, al-Andalus, and the Mediterranean Basin.

[13] Sufi literature played an important role in literary and intellectual life in the region from this early period, such as Muhammad al-Jazuli's book of prayers Dala'il al-Khayrat.

[5] Jamāl ad-Dīn al-Afghānī and Muhammad Abduh founded the revolutionary anti-colonial pan-Islamic journal Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa,[5] Abd al-Rahman al-Kawakibi, Qasim Amin, and Mustafa Kamil were reformers who influenced public opinion with their writing.

[5]Walī ad-Dīn Yakan [ar] launched a newspaper called al-Istiqama (الاستقامة, " Righteousness") to challenge Ottoman authorities and push for social reforms, but they shut it down in the same year.

[28] The rise of an efendiyya, an elite, secularist urban class with a Western education, gave way to new forms of literary expression: modern Arabic fiction.

[20] This new bourgeois class of literati used theater from the 1850s, starting in Lebanon, and the private press from the 1860s and 1870s to spread its ideas, challenge traditionalists, and establish its position in a rapidly transforming society.

[20] The modern Arabic novel, particularly as a means of social critique and reform, has its roots in a deliberate departure from the traditionalist language and aesthetics of classical adab for "less embellished but more entertaining narratives.

"[20] Writers such as Muhammad Taimur [ar] of Al-Madrasa al-Ḥadītha "the Modern School," calling for an adab qawmī "national literature," largely avoided the novel and experimented with short stories instead.

[20] As a result of increasing industrialization and urbanization, binary struggles such as the "materialism of the West" against the "spiritualism of the East," "progressive individuals and a backward, ignorant society," and "a city-versus-countryside divide" were common themes in the literature of this period and since.

Most of these experiments were abandoned in favour of prose poetry, of which the first examples in modern Arabic literature are to be found in the writings of Francis Marrash,[30] and of which two of the most influential proponents were Nazik al-Malaika and Iman Mersal.

Other caliphs followed after 'Abd al-Malik made Arabic the official language for the administration of the new empire, such as al-Ma'mun who set up the Bayt al-Hikma in Baghdad for research and translations.

Classical Arabic culinary literature is comprised not only of cookbooks, there are also many works of scholarship, and descriptions of contemporary foods can be found in fictional and legendary tales like The Thousand and One Nights.

Galen's On the Properties of Foodstuffs was translated into Arabic as Kitab al-aghdiya and was cited by all contemporary medical writers in the Caliphate during the reign of Abu Bakr al-Razi.

These were collections of facts, ideas, instructive stories and poems on a single topic, and covers subjects as diverse as house and garden, women, gate-crashers, blind people, envy, animals and misers.

Sex manuals were also written such as The Perfumed Garden, Ṭawq al-Ḥamāmah or The Dove's Neckring by ibn Hazm and Nuzhat al-albab fi-ma la yujad fi kitab or Delight of Hearts Concerning What will Never Be Found in a Book by Ahmad al-Tifashi.

Countering such works are one like Rawdat al-muhibbin wa-nuzhat al-mushtaqin or Meadow of Lovers and Diversion of the Infatuated by ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah who advises on how to separate love and lust and avoid sin.

Literary criticism was also employed in other forms of medieval Arabic poetry and literature from the 9th century, notably by Al-Jahiz in his al-Bayan wa-'l-tabyin and al-Hayawan, and by Abdullah ibn al-Mu'tazz in his Kitab al-Badi.

The 10th-century Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity features a fictional anecdote of a "prince who strays from his palace during his wedding feast and, drunk, spends the night in a cemetery, confusing a corpse with his bride.

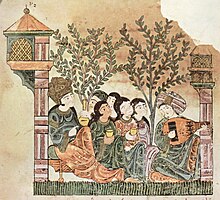

The main characters of the tale are Bayad, a merchant's son and a foreigner from Damascus, and Riyad, a well-educated girl in the court of an unnamed Hajib (vizier or minister) of 'Iraq which is referred to as the lady.

While dealing with serious topics in what are now known as anthropology, sociology and psychology, he introduced a satirical approach, "based on the premise that, however serious the subject under review, it could be made more interesting and thus achieve greater effect, if only one leavened the lump of solemnity by the insertion of a few amusing anecdotes or by the throwing out of some witty or paradoxical observations.

Due to cultural differences, they disassociated comedy from Greek dramatic representation and instead identified it with Arabic poetic themes and forms, such as hija (satirical poetry).

Ibn al-Nafis described his book Theologus Autodidactus as a defense of "the system of Islam and the Muslims' doctrines on the missions of Prophets, the religious laws, the resurrection of the body, and the transitoriness of the world."

Rather than giving supernatural or mythological explanations for these events, Ibn al-Nafis attempted to explain these plot elements using his own extensive scientific knowledge in anatomy, biology, physiology, astronomy, cosmology and geology.

[75][76] Marcia Lynx Qualey, editor-in-chief of ArabLit online magazine, has translated Arabic novels for young readers, such as Thunderbirds by Palestinian writer Sonia Nimr.

The poetry of Saniya Salih (Syria, 1935–85) appeared in many well-known magazines of her time, particularly Shi’r and Mawaqif, but remained in the shadow of work by her husband, the poet Muhammad al-Maghout.

[citation needed] In Algeria, women's oral literature used in ceremonies called Būqālah, also meaning ceramic pitcher, became a symbol of national identity and anti-colonialism during the War of Independence in the 1950s and early 60s.

Although nothing which might be termed 'literary criticism' in the modern sense, was applied to a work held to be i'jaz or inimitable and divinely inspired, textual analysis, called ijtihad and referring to independent reasoning, was permitted.

Taha Hussayn, himself well versed in European thought, would even dare to examine the Qur'an with modern critical analysis, in which he pointed out ideas and stories borrowed from pre-Islamic poetry.