Arabic grammar

Unlike in other dialects, first person singular verbs in Maghrebi Arabic begin with a n- (ن).

The identity of the oldest Arabic grammarian is disputed; some sources state that it was Abu al-Aswad al-Du'ali, who established diacritical marks and vowels for Arabic in the mid-600s,[1] Others have said that the earliest grammarian would have been Ibn Abi Ishaq (died AD 735/6, AH 117).

[2] The differences were polarizing in some cases, with early Muslim scholar Muhammad ibn `Isa at-Tirmidhi favoring the Kufan school due to its concern with poetry as a primary source.

[9] Early Arabic grammars were more or less lists of rules, without the detailed explanations which would be added in later centuries.

If the preceding word ends in a sukūn (سُكُون), meaning that it is not followed by a short vowel, the hamzat al-waṣl assumes a kasrah /i/.

The second-person masculine plural past tense verb ending -tum changes to the variant form -tumū before enclitic pronouns, e.g. كَتَبْتُمُوهُ katabtumūhu "you (masc.

Note in particular: In a less formal Arabic, as in many spoken dialects, the endings -ka, -ki, and -hu and many others have their final short vowel dropped, for example, كِتابُكَ kitābuka would become كِتابُك kitābuk for ease of pronunciation.

There are two demonstratives (أَسْماء الإشارة asmā’ al-ishārah), near-deictic ('this') and far-deictic ('that'): The dual forms are only used in very formal Arabic.

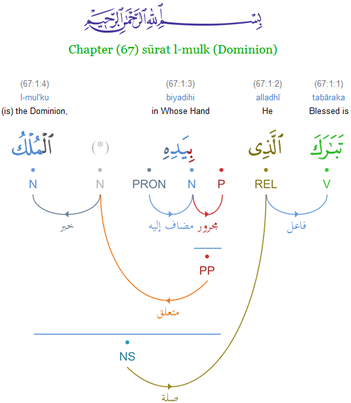

Similarly, the relative pronoun alladhī was originally composed based on the genitive singular dhī, and the old Arabic grammarians noted the existence of a separate nominative plural form alladhūna in the speech of the Hudhayl tribe in Qur'anic times.

The relative pronoun is declined as follows: Note that the relative pronoun agrees in gender, number and case, with the noun it modifies—as opposed to the situation in other inflected languages such as Latin and German, where the gender and number agreement is with the modified noun, but the case marking follows the usage of the relative pronoun in the embedded clause (as in formal English "the man who saw me" vs. "the man whom I saw").

It is very common, even by news announcers and in official speeches, to pronounce numerals in local dialects.

The gender of عَشَر in numbers 11–19 agrees with the counted noun (unlike the standalone numeral 10 which shows polarity).

Ordinal numerals (الأعداد الترتيبية al-a‘dād al-tartībīyah) higher than "second" are formed using the structure fā‘ilun, fā‘ilatun, the same as active participles of Form I verbs: They are adjectives, hence there is agreement in gender with the noun, not polarity as with the cardinal numbers.

Changes to the vowels in between the consonants, along with prefixes or suffixes, specify grammatical functions such as tense, person and number, in addition to changes in the meaning of the verb that embody grammatical concepts such as mood (e.g. indicative, subjunctive, imperative), voice (active or passive), and functions such as causative, intensive, or reflexive.

Since Arabic lacks a verb meaning "to have", constructions using li-, ‘inda, and ma‘a with the pronominal suffixes are used to describe possession.

In many cases the two members become a fixed coined phrase, the idafah being used as the equivalent of a compound noun used in some Indo-European languages such as English.

Though early accounts of Arabic word order variation argued for a flat, non-configurational grammatical structure,[24][25] more recent work[23] has shown that there is evidence for a VP constituent in Arabic, that is, a closer relationship between verb and object than verb and subject.

An analysis such as this one can also explain the agreement asymmetries between subjects and verbs in SVO versus VSO sentences, and can provide insight into the syntactic position of pre- and post-verbal subjects, as well as the surface syntactic position of the verb.

In such clauses, the subject tends to precede the predicate, unless there is a clear demarcating pause between the two, suggesting a marked information structure.

Because the verb agrees with the subject in person, number, and gender, no information is lost when pronouns are omitted.

[32] Regarding subject-verb order, Owens et al. (2009), examined three dialects of the Arabian peninsula from a discourse informational and a morpholexical perspective.

[33] Owens et al. (2009) argue that verb-subject order usually presents events, while subject-verb indicates available referentiality.

[34] El-Yasin (1985) examined colloquial Jordanian Arabic, and concluded that it exhibits a SVO order.

[37] Despite the analysis that both VS and SV typologies are found in spoken Arabic dialects (Moroccan, Egyptian, Syrian, and Kuwaiti), Brustad, K. (2000) notes that sentence typologies found in spoken Arabic are not limited to these two word orders.

’Inna, along with its related terms (or أَخَوَات ’akhawāt "sister" terms in the native tradition) أَنَّ anna 'that' (as in "I think that ..."), inna 'that' (after قَالَ qāla 'say'), وَلٰكِنَّ (wa-)lākin(na) 'but' and كَأَنَّ ka-anna 'as if' introduce subjects while requiring that they be immediately followed by a noun in the accusative case, or an attached pronominal suffix.

'inna wa ’akhawātuha As a particle, al- does not inflect for gender, number, person, or grammatical case.

[39] It consists of a verbal noun derived from the main verb that appears in the accusative (منصوب manṣūb) case.

The definite article اَلـ al- is a clitic, as are the prepositions لِـ li- 'to' and بِـ bi- 'in, with' and the conjunctions كَـ ka- 'as' and فَـ fa- 'then, so'.

An overhaul of the native systematic categorization of Arabic grammar was first suggested by the medieval philosopher al-Jāḥiẓ, though it was not until two hundred years later when Ibn Maḍāʾ wrote his Refutation of the Grammarians that concrete suggestions regarding word order and linguistic governance were made.

[40] In the modern era, Egyptian litterateur Shawqi Daif renewed the call for a reform of the commonly used description of Arabic grammar, suggesting to follow trends in Western linguistics instead.