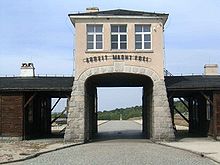

Arbeit macht frei

Following the Nazi Party's rise to power in 1933, the phrase became a slogan used in employment programs put into effect to combat mass unemployment in Germany at the time.

[2] Given its usage in conjunction with the forced labor and mass killings of the concentration camps, the word "free" took on a double meaning.

by Auguste Forel, a Swiss entomologist, neuroanatomist and psychiatrist, in his Fourmis de la Suisse (English: Ants of Switzerland) (1920).

[6] In 1922, the Deutsche Schulverein of Vienna, an ethnic nationalist "protective" organization of Germans within Austria, printed membership stamps with the phrase Arbeit macht frei.

[citation needed] The phrase is also evocative of the medieval German principle of Stadtluft macht frei ("urban air makes you free"), according to which serfs were liberated after being a city resident for one year and one day.

The slogan Arbeit macht frei was first used over the gate of the Oranienburg concentration camp,[8] which was set up in an abandoned brewery in March 1933 (it was later rebuilt in 1936 as Sachsenhausen).

[13][14][15] In The Kingdom of Auschwitz, Otto Friedrich wrote about Rudolf Höss, regarding his decision to display the motto so prominently at Auschwitz: He seems not to have intended it as a mockery, nor even to have intended it literally, as a false promise that those who worked to exhaustion would eventually be released, but rather as a kind of mystical declaration that self-sacrifice in the form of endless labor does in itself bring a kind of spiritual freedom.

[24] It was found on 28 November 2016 under a tarp at a parking lot in Ytre Arna, a settlement north of Bergen, Norway's second-largest city.