Architecture of Finland

[4]In a 2000 review article of twentieth century Finnish architecture, Frédéric Edelmann, arts critic of the French newspaper Le Monde, suggested that Finland has more great architects of the status of Alvar Aalto in proportion to the population than any other country in the world.

As an essentially forested region, timber has been the natural building material, while the hardness of the local stone (predominantly granite) initially made it difficult to work, and the manufacture of brick was rare before the mid-19th century.

The castle is built on an island in the Kyrönsalmi strait that connects the lakes Haukivesi and Pihlajavesi; the design was based on the idea of 3 large towers in a line facing north-west and an encircling wall.

This led to a rethinking of Sweden's defence policies, including the creation of more fortification works in eastern Finland, but in particular the founding of the fortress town of Fredrikshamn (Hamina), with the first plan by Axel von Löwen in 1723.

[22] The czar appointed the military engineer Johan Albrecht Ehrenström, a former courtier of Sweden's King Gustavus III, as head of the reconstruction committee, with the task of drawing up a plan for a new stone-built capital.

In the words of art historian Riitta Nikula, Ehrenström created "the symbolic heart of the Grand Duchy of Finland, where all the main institutions had an exact place dictated by their function in the hierarchy.

"[8] In fact, even before the ceding of Finland to Russia in 1809, the advent of Neoclassicism in the mid-18th century arrived with French artist-architect Louis Jean Desprez, who was employed by the Swedish state, and who designed Hämeenlinna church in 1799.

In addition to churches, the neo-Gothic style was also dominant for the buildings of the growing industrial manufacturers, including the Verla mill in Jaala (1892) - nowadays a World Heritage Site - designed by Edward Dippel.

[37] One hundred years later it was also still quite rare; e.g. notable revivalist-style architect Karl August Wrede studied architecture in Dresden, and Theodor Höijer at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts in Stockholm.

Engel's neoclassical Helsinki University Library (1845), demonstrates both an outwardly stylistic continuity with the original - albeit the pilasters have not classical capitals but reliefs, made by the sculptor Walter Runeberg, personifying the sciences - whilst also employing modern techniques in the Art Nouveau interior: the semicircular 6-storey extension comprises a large light-well surrounded by radially placed bookshelves.

[38] Usko Nyström's chief work, the Grand Hôtel Cascade, Imatra (1903) (nowadays called Imatran Valtionhotelli), is a key Jugendstil style building; the "wilderness hotel", built next to the impressive Imatra Rapids (the biggest in Finland), was intended mostly for wealthy tourists from the Russian Imperial capital of Saint Petersburg, while its architectural style was inspired by Finnish National Romanticism, whilst taking its inspiration partly from the medieval and neo-Renaissance French châteaux Usko Nyström had seen during his time in France.

[40] In 1889 the artist Albert Edelfelt depicted the national awakening in a poster showing Mme Paris receiving Finland, a damsel, who alights with a model of St Nicholas' Church (later Helsinki Cathedral) on her hat; the parcels in the boat are all marked EU (i.e. Exposition Universelle).

A distinct symbolic importance was given in 1900 to Finland receiving its own pavilion at the Paris World Expo, designed by young architects Herman Gesellius, Armas Lindgren and Eliel Saarinen in the so-called Jugendstil style (or Art Nouveau) then popular in Central Europe.

[41] The Jugendstil style in Finland is characterised by flowing lines and the incorporation of nationalistic-mythological symbols - especially those taken from the national epic, Kalevala - mostly taken from nature and even medieval architecture, but also contemporary sources elsewhere in Europe and even the USA (e.g. H.H.

Historian Pekka Korvenmaa makes the point that leading theme was the creation of the atmosphere of medieval urban environments - and Sonck later designed a similar proposal in 1904 to rearrange the immediate surroundings of St.Michael's Church in Helsinki, with numerous "fantastic" spired buildings.

The scheme was equally inspired by the Parisian axiality of Haussman, the intimate residential squares of Raymond Unwin in the English garden cities and the large-scale apartment blocks of Otto Wagner in Vienna.

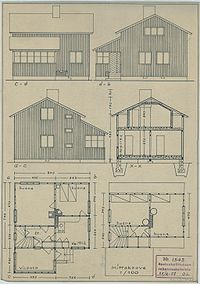

In 1922 the National Board of Social Welfare (Sosiaalihallitus) commissioned architect Elias Paalanen to design different options of farmhouses, which were then published as a brochure, Pienasuntojen tyyppipiirustuksia (Standard drawings for small houses) republished several times.

A number of these houses ended up being exported from the Soviet Union to various places in Poland, where small "Finnish villages" were established; for example, the district of Szombierki in Bytom, as well as in Katowice and Sosnowiec.

...let us add some circles – called medallions – between the windows on some floors, and to demonstrate sensitive artistry, we find a delicate dangling clothesline of a garland, or a flattened-out meander, or even a gilt star, which is an extremely 'elegant' solution.

[53] The shift or transition from Nordic Classicism to Functionalism is said sometimes to have been sudden and revolutionary, as with Aalto's Turku Sanomat newspaper offices and Paimio Sanatorium, which employs such distinct modernist features as use of reinforced concrete construction, steel strip windows and flat roofs.

Traces of Nordic Classicism would naturally continue synthesized with Functionalism and a more idiosyncratic individual style, a well-known example being Erik Bryggman's mature work, the Resurrection Chapel in Turku, dating from as late as 1941.

The major example of the goal to set living within nature was Tapiola garden city, located in Espoo, promoted by its founder Heikki von Hertzen to encourage social mobility.

For example, in the Otavamedia (publishers) offices in Länsi-Pasila, Helsinki (1986) by Ilmo Valjakka, postmodern versions of central and southern European details such as corner towers, blind (i.e. unusable) colonnades and scenographic bridges, are added to the overall mass.

Also, in the BePOP shopping centre (1989), Pori, by Nurmela-Raimoranta-Tasa architects, for all its idiosyncratic postmodern interior and curved "medieval" street cutting through the building, the overall urban block still fits within strict height parameters for the area.

The Kankaanpää public office centre (1994) by architects Sinikka Kouvo and Erkki Partanen applied a "heterotopic" ordering – clashes of different volumes – previously discernible in the mature work of Aalto but with a postmodernist twist of Mario Botta-esque "round houses" and striking striped bands of brickwork.

[81] Already in 1956 Alvar Aalto argued that the use of wood was not a nostalgic return to a traditional material; it was a case of its "biological characteristics, its limited heat conductivity, its kinship with man and living nature, the pleasant sensation to the touch that it gives.".

The Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Warsaw, Poland (2013), by Lahdelma & Mahlamäki is characterised by the principle of "complex objects in a glass box", including parametrically designed organic forms.

[40] The former industrial, dockyard and shipbuilding areas of Helsinki are being replaced by new housing areas, designed mostly in a minimalist-functionalist style as well as new support services such as kindergartens and schools (which, for the sake of efficiency, are also intended for use as neighbourhood communal facilities; e.g. Opinmäki School and multipurpose centre [2016] by Esa Ruskeepää), as well allowing for large-scale shopping malls (e.g. the new districts of Ruoholahti, Arabianranta, Vuosaari, Hernesaari, Hanasaari, Jätkäsaari and Kalasatama), projects often driven forward by architecture and urban planning competitions.

Many of the leading works of architecture at the turn of that century were the results of competitions: e.g. Tampere Cathedral (Lars Sonck, 1900), National Museum, Helsinki (Herman Gesellius, Armas Lindgren and Eliel Saarinen, 1902).

But before Aalto, the first significant event in direct influence was Eliel Saarinen emigrating to the United States in 1923 - after having received second prize in the Chicago Tribune Tower competition of 1922 - where he was responsible for the design of the campus for the Cranbrook Academy of Art, Michigan.