Byzantine architecture

Precious wood furniture, like beds, chairs, stools, tables, bookshelves and silver or golden cups with beautiful reliefs, decorated Byzantine interiors.

Stylistic drift, technological advancement, and political and territorial changes meant that a distinct style gradually resulted in the Greek cross plan in church architecture.

[3] Civil architecture continued Greco-Roman trends; the Byzantines built impressive fortifications and bridges, but generally not aqueducts on the same scales as the Romans.

This terminology was introduced by modern historians to designate the medieval Roman Empire as it evolved as a distinct artistic and cultural entity centered on the new capital of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) rather than the city of Rome and its environs.

This new style with exotic domes and richer mosaics would come to be known as "Byzantine" before it traveled west to Ravenna and Venice and as far north as Moscow.

Byzantine capitals break away from the Classical conventions of ancient Greece and Rome with sinuous lines and naturalistic forms, which are precursors to the Gothic style.

[4] Byzantine columns are quite varied, mostly developing from the classical Corinthian, with the ornamentation undercut with drills, and fluted shafts almost entirely abandoned.

One of the most remarkable designs features leaves carved as if blown by the wind; the finest example being at the 7th-century Hagia Sophia (Thessaloniki).

The columns at Basilica of San Vitale show wavy and delicate floral patterns similar to decorations found on belt buckles and dagger blades.

Buildings increased in geometric complexity, brick and plaster were used in addition to stone in the decoration of important public structures, classical orders were used more freely, mosaics replaced carved decoration, complex domes rested upon massive piers, and windows filtered light through thin sheets of alabaster to softly illuminate interiors.

Prime examples of early Byzantine architecture date from the Emperor Justinian I's reign and survive in Ravenna and Istanbul, as well as in Sofia (the Church of St Sophia).

In Ravenna, the longitudinal basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, and the octagonal, centralized structure of the church of San Vitale, commissioned by Emperor Justinian but never seen by him, was built.

A mosaic in the church begun by the Ostrogoths, San Apollinare in Nuovo in Ravenna, depicts an early Byzantine palace.

In the Macedonian dynasty, it is presumed that Basil I's votive church of the Theotokos of the Pharos and the Nea Ekklesia (both no longer existent) served as a model for most cross-in-square sanctuaries of the period, including the Cattolica di Stilo in southern Italy (9th century), the monastery church of Hosios Lukas in Greece (c. 1000), Nea Moni of Chios (a pet project of Constantine IX), and the Daphni Monastery near Athens (c. 1050).

[5] The Hagia Sophia church in Ochrid (present-day North Macedonia), built in the First Bulgarian Empire in the time of Boris I of Bulgaria, and eponymous cathedral in Kiev (present-day Ukraine) testify to a vogue for multiple subsidiary domes set on drums, which would gain in height and narrowness with the progress of time.

Similar styles can be found in countries such as Bulgaria, Croatia, North Macedonia, Russia, Serbia and other Slavic lands, as well as in Sicily (Cappella Palatina) and Veneto (St Mark's Basilica, Torcello Cathedral).

In Middle Byzantine architecture "cloisonné masonry" refers to walls built with a regular mix of stone and brick, often with more of the latter.

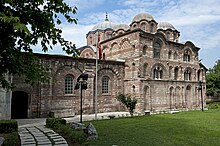

The Church of the Holy Apostles (Thessaloniki) is cited as an archetypal structure of the late period with its exterior walls intricately decorated with complex brickwork patterns or with glazed ceramics.

Other churches from the years immediately predating the fall of Constantinople survive on Mount Athos and in Mistra (e.g. Brontochion Monastery).

[6] It displays the attenuated proportions favored in the late Byzantine era, as well as shifts in style in the mosaics' treatment of figures.

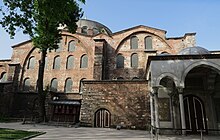

Vaults appear to have been early applied to the basilican type of plan; for instance, at Hagia Irene, Constantinople (6th century), the long body of the church is covered by two domes.

At Saint Sergius, Constantinople, and San Vitale, Ravenna, churches of the central type, the space under the dome was enlarged by having apsidal additions made to the octagon.

Above the conchs of the small apses rise the two great semi-domes which cover the hemicycles, and between these bursts out the vast dome over the central square.

On the two sides, to the north and south of the dome, it is supported by vaulted aisles in two stories which bring the exterior form to a general square.

After the 6th century there were no churches built which in any way competed in scale with these great works of Justinian, and the plans more or less tended to approximate to one type.

The central area covered by the dome was included in a considerably larger square, of which the four divisions, to the east, west, north and south, were carried up higher in the vaulting and roof system than the four corners, forming in this way a sort of nave and transepts.

Now add three apses on the east side opening from the three divisions, and opposite to the west put a narrow entrance porch running right across the front.

[10][11][9] The Hagia Sophia held the title of largest church in the world until the Ottoman Empire sieged the Byzantine capital.

[13] The original construction of Hagia Sophia was possibly ordered by Constantine, but ultimately carried out by his son Constantius II in 360.