Architecture of Melbourne

[12][13] The original inhabitants, the Wurundjeri were known to have created temporary structures called Mia-mia out of bark, saplings and timber and were observed by Protector of Aborigines William Thomas to be comfortably housed.

Part of St Francis Church on the corner of Lonsdale and Elizabeth streets dates to 1842, the simple construction is Melbourne's oldest Gothic revival building, though its original form was later significantly augmented and altered.

[38] A two-storey colonial regency style shop on the corner of King and Latrobe Street (1850) is recognised as the oldest known building in the Hoddle grid with an unmodified original appearance.

[39] The Duke of Wellington Hotel on Flinders Street (1850), another modest two-storey Georgian style building, is also believed to date to this era and is cited as the oldest public bar in the Hoddle grid.

Locally quarried bluestone (basalt) was a distinctive construction material used from Melbourne's earliest days however it became increasingly popular during the gold rush for institutional buildings due to its heavy rusticated effect and its stern, foreboding appearance.

HM Prison Pentridge (1851) is particularly notable as one of the largest gold rush era bluestone buildings as well as for its distinctive castellated Tudor appearance incorporating medieval style watch towers, arrow slits and panopticons.

[114] Joseph Reed's design for Collins Street Independent Church (1866) (now St Michael's) is notable not only as the earliest examples of elaborate polychrome brickwork in Australia (a style that became highly popular by the 1880s) but also for its unusual floorplan and tower.

It features a sloping floor with tiered seating, and a steep gallery behind a ring of high aches on slender cast iron columns, ensuring good sight lines.

The 1880s saw the price of land start to boom, and London banks were eager to extend loans to men of vision who capitalised on this by speculation, and grand, elaborate offices, hotel and department stores in the city, and endless suburban subdivisions.

[124] Designed by English architect William Butterfield, it occupied a prominent site in the heart of the city on Flinders Street at the entrance of Princes Bridge making it a highly visible landmark even without its later completed spires.

[147] The Former Priory Ladies School (1890) in Alma Road St Kilda demonstrates a rare shift away from the gothic idiom to the American Romanesque, following EG Kilburn's visit to the United States.

Elleker and Kilburn's Melbourne City Building (1888) is an unusual early Queen Anne design which forms a pair with the towered Colonial Bank Hotel (1888) across Balcombe Place.

[166] Renaissance Revival of the gold rush period continued to be popular even with the larger banks and socieities from the Smith and Johnson designed Melbourne Savage Club building (1884-1885)[167] to the six storey Former Money Order Post Office (1890).

[168] However academic classicism was often seen as too restrained for the boom style and architects sometimes gave them a more baroque flavour, as in Sum Kum Lee at Chinatown (1887-1888) by George De Lacy Evans[169] and William Salway's design for the Collins Street Mercantile Bank (1888).

[183] Melbourne's tram and railway systems boomed during the period, resulting in many significant station and terminus buildings mostly constructed in red brick of the Queen Anne style.

The local architects sought technical advice from Fazlur Khan of renowned American architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), spending 10 weeks at their Chicago office in 1968.

Melbourne's modern legacy began to give way in the 1980s with the culmination of a strong postmodern movement as many decried the continued loss of the city's cultural character and European charm.

It was the first major project to successfully integrate the old and new, preserving and restoring a significant Victorian streetscape including Grosvenor Chambers (1888), Leonard Terry's Campbell House (1877) and a row of three storey Lloyd Tayler designed terraces (1884).

One Collins' stepped form, setback style, elegantly minimilist square windows and cut stone-like texture established a strong reputation for emerging firm Denton Corker Marshall (DCM).

Firstly their work in 222 Exhibition Street (TAC House) (1986–88) made an explicit statement against the dominance of glass curtain wall design of the late international style using open steel grill elements, scale, symmetry and a differentiated podium.

90 Collins Street (1987) by Peck von Hartel preserved a Victorian era professional building and mirroring it to create a symmetrical central entrance under a mock stone faced North American style stepped tower, a design model applied successfully by New York's similarly dated 712 Fifth Avenue.

Southbank Promenade designed by Denton Corker Marshall in 1990 featured smoothly cut bluestone and metal ornaments which were highly fashionable and helped revived Melbourne's southern riverfront.

Kurokawa's original design for Melbourne Central including its podium featuring a geodesic dome, concave and large faceted oriel windows were lost to remodelling done by ARM in 2006.

Designed by architects and World War I veterans Phillip Hudson and James Wardrop, the Shrine is built in a classical style and is based on the Tomb of Mausolus at Halicarnassus and the Parthenon in Athens, Greece.

Beneath the sanctuary lies a crypt, which contains a bronze statue of a soldier father and son representing two generations, as well as panels listing every unit of the Australian Imperial Force.

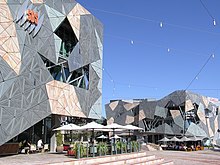

The paving is designed as a huge urban artwork, called Nearamnew, by Paul Carter and gently rises above street level, containing a number of textual pieces inlaid in its undulating surface.

Cathedral Arcade, in the Nicholas Building (1927), was built in the art deco style and reflects Melbourne's 1920s architecture with glass domes, leadlight, arches, and shopfronts with detailed wood paneling.

[286]Another venue that shaped Melbourne's early architectural form is the pub, a licensed drinking establishment traditionally built on corners within the inner-city and city centre, usually no more than two-storeys tall.

[287] In 1972, as a result of sustained pressure from the National Trust, Victorian Parliament amended the Town and Country Planning Act to include the "conservation and enhancement of buildings, works, objects and sites specified as being of architectural, historical or scientific interest".

In this context, as well as the many places demolished in the 1960s sometimes without a plan for a replacement, "developers white elephant schemes for central Melbourne proceeded virtually unchecked throughout the 70s", resulting in widespread loss of historic buildings.