Indigenous architecture

[citation needed] Labelling Indigenous Australian communities as 'nomadic' allowed early settlers to justify the takeover of Traditional Lands claiming that they were not inhabited by permanent residents.

[3][4][5] These builders utilised basalt rocks around Lake Condah to erect housing and complicated systems of stone weirs, fish, and eel traps, and gates in water-course creeks.

Rapid population growth, shorter lifetimes for housing stock, and rising construction costs have meant that efforts to limit overcrowding and provide healthy living environments for Indigenous people have been difficult for governments to achieve.

The application of evidence-based research and consultation has led to museums, courts, cultural centres, keeping houses, prisons, schools, and a range of other institutional and residential buildings being designed to meet the varying and differing needs and aspirations of Indigenous users.

The wigwam, (otherwise known as wickiup or wetu), tipi, and snow house were building forms perfectly suited to their environments and to the requirements of mobile hunting and gathering cultures.

Not familiar to this sedentary lifestyle, many of these people continued to using their traditional hunting grounds, but when much of southern Canada was settled in the late 1800s and early 1900s, this practice ceased ending their nomadic way of life.

[citation needed] As health services on Indigenous reserves increased during the 1950s and 1960s, life expectancy greatly improved including dramatic drop in the infant mortality, though this may have exacerbated the existing overcrowding problem.

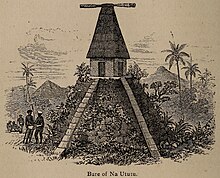

A village structure shares similarities today but built with modern materials and spirit houses (Bure Kalou) have been replaced by churches of varying design.

Inside the hut, a hearth is built on the floor between the entrance and the centre pole that defines a collective living space covered with pandanus leaf (ixoe) woven mats, and a mattress of coconut leaves (behno).

It was named after Jean-Marie Tjibaou, the leader of the independence movement who was assassinated in 1989 and who had a vision of establishing a cultural centre which blended the linguistic and artistic heritage of the Kanak people.

The formal curved axial layout, 250 metres (820 ft) long on the top of the ridge, contains ten large conical cases or pavilions (all of different dimensions) patterned on the traditional Kanak Grand Hut design.

"[75] The building plans, spread over an area of 8,550 square metres (92,000 sq ft) of the museum, were conceived to incorporate the link between the landscape and the built structures in the Kanak traditions.

Thus, the planning aimed at a unique building which would be, as the architect Piano stated, "to create a symbol and ...a cultural centre devoted to Kanak civilization, the place that would represent them to foreigners that would pass on their memory to their grand children".

The model as finally built evolved after much debate in organized 'Building Workshops' in which Piano's associate, Paul Vincent and Alban Bensa, an anthropologist of repute on Kanak culture were also involved.

[78] The centre comprises an interconnected series of ten stylised grandes cases (chiefs' huts), which form three villages (covering an area of 6060 square metres).

These huts have an exposed stainless-steel structure and are constructed of iroko, an African rot-resistant timber which has faded over time to reveal a silver patina evocative of the coconut palms that populate the coastline of New Caledonia.

Similarly, the soaring huts appear unfinished as they open outward to the sky, projecting the architect's image of Kanak culture as flexible, diasporic, progressive and resistant to containment by traditional museological spaces.

Other important architectural projects have included the construction of the Mwâ Ka, 12m totem pole, topped by a grande case (chief's hut) complete with flèche faîtière standing in a landscaped square opposite Musée de Nouvelle-Calédonie.

Many traditional island building-techniques were retained, using new materials: raupo reed, toetoe grass, aka vines[79] and native timbers: totara, pukatea, and manuka.

The marae was the central place of the village where culture can be celebrated and intertribal obligations can be met and customs can be explored and debated, where family occasions such as birthdays can be held, and where important ceremonies, such as welcoming visitors or farewelling the dead (tangihanga), can be performed.

In contemporary context these generally comprise a group of buildings around an open space, that frequently host events such as weddings, funerals, church services and other large gatherings, with traditional protocol and etiquette usually observed.

[117] A tall roof created space above the living area through which warm air could rise, giving the Bahay Kubo a natural cooling effect even during the hot summer season.

The steep pitch allowed water to flow down quickly at the height of the monsoon season while the long eaves gave people a limited space to move about around the house's exterior whenever it rained.

Old men or women then beat the husk with a mallet on a wooden anvil to separate the fibres, which, after a further washing to remove interfibrous material, are tied together in bundles and dried in the sun.

The space also defines the position where the 'ava makers (aumaga) in the Samoa 'ava ceremony are seated and the open area for the presentation and exchanging of cultural items such as the 'ie toga fine mats.

In modern times, with the decline of traditional architecture and the availability of western building materials, the shape of the fale tele has become rectangular, though the spatial areas in custom and ceremony remain the same.

In general, the timbers most frequently used in the construction of Samoan houses are:- Posts (poutu and poulalo): ifi lele, pou muli, asi, ulu, talia, launini'u and aloalovao.

Protection from sun, wind or rain, as well as from prying eyes, was achieved by suspending from the fau running round the house several of a sort of drop-down Venetian blind, called pola.

A goahti (also gábma, gåhte, gåhtie and gåetie, Norwegian: gamme, Finnish: kota, Swedish: kåta), is a Sami hut or tent of three types of covering: fabric, peat moss or timber.

The Sámi Parliament building was designed by the (non-Sámi) architects Stein Halvorsen & Christian Sundby, who won the Norwegian government's call for projects in 1995, and inaugurated in 2005.