Longhouses of the Indigenous peoples of North America

Longhouses were a style of residential dwelling built by Native American and First Nations peoples in various parts of North America.

Scholars believe walls were made of sharpened and fire-hardened poles (up to 1,000 saplings for a 50 m (160 ft) house) driven close together into the ground.

The frame is covered by bark that is sewn in place and layered as shingles, and reinforced by light swag.

Ventilation openings, later singly dubbed as a smoke pipe, were positioned at intervals, possibly totalling five to six along the roofing of the longhouse.

On average a typical longhouse was about 24.4 by 5.5 by 5.5 m (80 by 18 by 18 ft) and was meant to house up to twenty or more families, most of whom were matrilineally related.

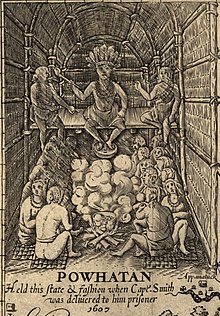

Protective palisades were built around the dwellings; these stood 4.3 to 4.9 m (14 to 16 ft) high, keeping the longhouse village safe.

Tribes or ethnic groups in northeast North America, south and east of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, which had traditions of building longhouses include the Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee): Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida and Mohawk.

Although the Shawnee were not known to build longhouses, colonist Christopher Gist describes how, during his visit to Lower Shawneetown in January 1751, he and Andrew Montour addressed a meeting of village leaders in a "Kind of State-House of about 90 Feet [27 m] long, with a light Cover of Bark in which they hold their Councils.

Usually an extended family occupied one longhouse, and cooperated in obtaining food, building canoes, and other daily tasks.

[2] The front is often very elaborately decorated with an integrated mural of numerous drawings of faces and heraldic crest icons of raven, bear, whale, etc.

The position of these poles depended on the lengths of the boards they held, and they were evidently set and reset through the years the houses were occupied.

Cuts and puncture marks indicated they served as work platforms; mats rolled out onto them tie with elders' memories of such benches used as beds.