Architecture of Norway

This, combined with the ready availability of wood as a building material, ensured that relatively few examples of the Baroque, Renaissance, and Rococo architecture styles so often built by the ruling classes elsewhere in Europe, were constructed in Norway.

[1][2] Construction in Norway has always been characterized by the need to shelter people, animals, and property from harsh weather, including predictably cold winters and frost, heavy precipitation in certain areas, wind and storms; and to make the most of scarce building resources.

[citation needed] Thanks to new digging methods like topsoil excavation, archeologists have been able to further uncover the remains or foundations of 400 prehistoric houses that were previously hidden beneath the ground.

The oldest surviving traces of construction in Norway dates back to about 9000 BC, in mountainous regions near Store Myrvatn in contemporary Rogaland, where excavations have found portable dwellings most likely kept by nomadic reindeer hunters.

At this point, the houses became larger and they gained a rectangular form, covering an area of 70 square meters (750 sq ft), as demonstrated at Gressbakken in Nesseby Municipality in Finnmark.

Many were destroyed as part of a religious movement that favored simple, puritan lines, and today only 28 remain, though a large number were documented and recorded by measured drawings before they were demolished.

[citation needed] The stave churches owe their longevity to architectural innovations that protected these large, complex wooden structures against water rot, precipitation, wind, and extreme temperatures.

Fortresses, such as Akershus in Oslo, Vardøhus in Vardø, Tønsberghus in Tønsberg, the Kongsgården in Trondheim and Bergenhus with the Rosenkrantz Tower in Bergen were built in stone in accordance with standards for defensive fortifications of their time.

[7] There are few examples of Renaissance architecture in Norway, the most prominent being the Rosenkrantz Tower in Bergen, Barony Rosendal in Hardanger, and the contemporary Austråt manor near Trondheim, and parts of Akershus Fortress.

[16][17] Christian IV undertook a number of projects in Norway that were largely based on Renaissance architecture[18] He established mining operations in Kongsberg and Røros, now a World Heritage Site.

After a devastating fire in 1624, the town of Oslo was moved to a new location and rebuilt as a fortified city with an orthogonal layout surrounded by ramparts, and renamed Christiania.

[21] Rococo provided a brief but significant interlude in Norway, appearing primarily in the decorative arts, and mainly in interiors, furniture and luxury articles such as table silver, glass and stoneware.

[22] In towns and central country districts during the 18th century, log walls were increasingly covered by weatherboards, a fashion made possible by sawmill technology.

He added a classical portico to the front of an older structure, and a semi-circular auditorium that was sequestered by Parliament in 1814 as a temporary place to assemble, now preserved at Norwegian Museum of Cultural History as a national monument.

The same period saw the erection of a large number of splendid neo-classicist houses in and around all towns along the coast, notably in Halden, Oslo, Drammen, Arendal, Bergen and Trondheim, mainly wooden buildings dressed up as stone architecture.

Linstow also planned Karl Johans gate, the avenue connecting the Palace and the city, with a monumental square halfway to be surrounded by buildings for the university, the Parliament (Storting) and other institutions.

Linstow was the first Norwegian architect to be inspired by the Middle Ages in his proposal of 1837 for a square to be surrounded by public building, bisected by an avenue between Christiania and the new Royal Palace.

[25] His classicist colleague Grosch was the first to convert to historicism and realize a number of red-brick buildings, after his 1838 visit to Berlin, where he met the famous architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel.

The Swiss chalet-style evolved into a Scandinavian variation, known in Norway as the "dragon style”, which combined motifs from Viking and medieval art with vernacular elements from the more recent past.

Centrally placed open-hearth fires with smoke vents in the roofs gave way to stone stoves and chimneys in early modern times.

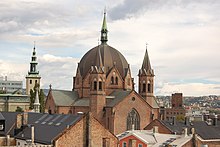

There was also a local Nordic variation, National Romantic style, with clear medieval inspirations, like the Norwegian University of Science and Technology main campus in Trondheim.

[30] Not unlike other countries during the evolution of their economies, Architecture became a tool for and manifestation of social policy, with architects and politicians determining just what features were adequate for the intended residents of housing projects.

As a result of the pioneering efforts by Olav Selvaag and others, archaic and otherwise unnecessary restrictions were relaxed, improving opportunities for more Norwegians to build housing to suit their individual needs and preferences.

Norwegian production of Mid-century modern furniture are known for clean lines, organic forms, and functional designs, using high-quality materials like teak, oak, and leather.

Brutalist architecture, characterized by its raw concrete forms and modular elements, found a distinct expression in Norway during the post-war period and particularly with the rise of the social democratic state.

These buildings, located in the heart of Oslo as part of the main offices of the Norwegian government, featured murals by Pablo Picasso, integrated into the concrete surfaces.

The Government Quarter suffered permanent damage in the 2011 terror attacks, and were ultimately demolished in 2020, a decision that underscored the ongoing tensions surrounding Brutalism’s legacy in Norway.

As Norway became an oil-rich nation, wealth from petroleum exports fueled urban expansion, infrastructure projects, and corporate developments, many of which embraced postmodern architectural styles during the 1980s and 1990s.

Therefore, Norwegian architecture from the late 1980s through the 1990s continued to be characterized by a shared commitment to the principles of a restrained modernism, focusing on the appropriate use of materials and rational, constructive solutions.

As Norway gained full independence in 1905, the national government determined to establish institutions consistent with the newly formed state's ambitions as a modern society.