Architecture of Samoa

[1] Architectural concepts are incorporated into Samoan proverbs, oratory and metaphors, as well as linking to other art forms in Samoa, such as boat building and tattooing.

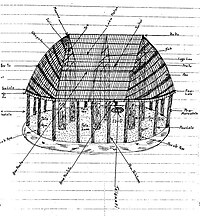

In general, traditional Samoan architecture is characterized by an oval or circular shape, with wooden posts holding up a domed roof.

The fale is lashed and tied together with a plaited sennit rope called ʻafa, handmade from dried coconut fibre.

Old men or women then beat the husk with a mallet on a wooden anvil to separate the fibres, which, after a further washing to remove interfibrous material, are tied together in bundles and dried in the sun.

When this stage is completed, the fibres are manufactured into sennit by plaiting, a task usually done by elderly men or matai, and performed at their leisure.

ʻAfa has many other uses in Samoan material culture, including ceremonial items, such as the fue fly whisk, a symbol of orator status.

The interior directions of a fale, east, west, north and south, as well as the positions of the posts, affect the seating positions of chiefs according to rank, the place where orators (host or visiting party) must stand to speak or the side of the house where guests and visitors enter and are seated.

The simplest types of fale are called faleoʻo, which have become popular as eco-friendly and low-budget beach accommodations in local tourism.

The Samoan word tufuga denotes the status of master craftsmen who have achieved the highest rank in skill and knowledge in a particular traditional art form.

The malae, (similar to the concept of marae in Māori and other Polynesian cultures), is usually a well-kept, grassy lawn or sandy area.

The malae is an important cultural space where interactions between visitors and hosts or outdoor formal gatherings take place.

In modern times, with the decline of traditional architecture and the availability of western building materials, the shape of the fale tele has become rectangular, though the spatial areas in custom and ceremony remain the same.

Popular as a "grass hut" or beach fale in village tourism, many are raised about a meter off the ground on stilts, sometimes with an iron roof.

In a village, families build a faleoʻo beside the main house or by the sea for resting during the heat of the day or as an extra sleeping space at night if there are guests.

In most villages, the umukuka is a simple open shed made with a few posts with an iron roof to protect the cooking area from the weather.

The main supporting posts, erected first, vary in number, size and length depending on the shape and dimensions of the house.

The soʻa extend from the poutu to the outside circumference of the fale and their ends are fastened to further supporting pieces called laʻau faʻalava.

The laʻau faʻalava, placed horizontally, are attached at their ends to wide strips of wood continuing from the faulalo to the auau.

At a distance of about 2 feet (0.61 m) between each are circular pieces of wood running around the house and extending from the faulalo to the top of the building.

On the framework are attached innumerable aso, thin strips of timber (about .5 by .25 inches (1.27 by 0.64 cm) by 12 to 25 feet (3.7 to 7.6 m) in length).

The main posts were from the breadfruit tree (ulu), or ifi lele or pou muli if this wood was not available.

[7] In general, the timbers most frequently used in the construction of Samoan houses are: Posts (poutu and poulalo): ifi lele, pou muli, asi, ulu, talia, launiniʻu and aloalovao.

Protection from sun, wind or rain, as well as from prying eyes, was achieved by suspending from the fau running round the house several of a sort of drop-down Venetian blind, called pola.

A sufficient number of pola to reach from the ground to the top of the poulalo are fastened together with ʻafa and are tied up or let down as the occasion demands.