Ancient Roman architecture

The period from roughly 40 BC to about 230 AD saw most of the greatest achievements, before the Crisis of the Third Century and later troubles reduced the wealth and organizing power of the central governments.

The administrative structure and wealth of the Empire made possible very large projects even in locations remote from the main centers,[1] as did the use of slave labor, both skilled and unskilled.

For the first time in history, their potential was fully exploited in the construction of a wide range of civil engineering structures, public buildings, and military facilities.

[7] A crucial factor in this development, which saw a trend toward monumental architecture, was the invention of Roman concrete (opus caementicium), which led to the liberation of shapes from the dictates of the traditional materials of stone and brick.

[10] The use of arches that spring directly from the tops of columns was a Roman development, seen from the 1st century AD, that was very widely adopted in medieval Western, Byzantine and Islamic architecture.

The same can be said in turn of Islamic architecture, where Roman forms long continued, especially in private buildings such as houses and the bathhouse, and civil engineering such as fortifications and bridges.

In Britain, a similar enthusiasm has seen the construction of thousands of neoclassical buildings over the last five centuries, both civic and domestic, and many of the grandest country houses and mansions are purely Classical in style, an obvious example being Buckingham Palace.

Travertine limestone was found much closer, around Tivoli, and was used from the end of the Republic; the Colosseum is mainly built of this stone, which has good load-bearing capacity, with a brick core.

[24] There is often little obvious difference (particularly when only fragments survive) between Roman bricks used for walls on the one hand, and tiles used for roofing or flooring on the other, so archaeologists sometimes prefer to employ the generic term ceramic building material (or CBM).

As early as the time of Augustus, a public basilica for transacting business had been part of any settlement that considered itself a city, used in the same way as the late medieval covered market houses of northern Europe, where the meeting room, for lack of urban space, was set above the arcades.

After Christianity became the official religion, the basilica shape was found appropriate for the first large public churches, with the attraction of avoiding reminiscences of the Greco-Roman temple form.

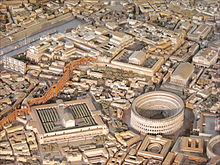

In addition to its standard function as a marketplace, a forum was a gathering place of great social significance, and often the scene of diverse activities, including political discussions and debates, rendezvous, meetings, etc.

"These horrea were divided and subdivided, so that one could hire only so much space as one wanted, a whole room (cella), a closet (armarium), or only a chest or strong box (arca, arcula, locus, loculus).

Common Roman apartments were mainly masses of smaller and larger structures, many with narrow balconies that present mysteries as to their use, having no doors to access them, and they lacked the excessive decoration and display of wealth that aristocrats' houses contained.

Wealthier Romans were often accompanied by one or more slaves, who performed any required tasks such as fetching refreshment, guarding valuables, providing towels, and at the end of the session, applying olive oil to their masters' bodies, which was then scraped off with a strigil, a scraper made of wood or bone.

Original marble columns of the Temple of Janus in Rome's Forum Holitorium, dedicated by Gaius Duilius after his naval victory at the Battle of Mylae in 260 BC,[46] still stand as a component of the exterior wall of the Renaissance era church of San Nicola in Carcere.

With the colossal Diocletian's Palace, built in the countryside but later turned into a fortified city, a form of residential castle emerges, that anticipates the Middle Ages.

The initial invention of the watermill appears to have occurred in the Hellenized eastern Mediterranean in the wake of the conquests of Alexander the Great and the rise of Hellenistic science and technology.

[58][59] Apart from its main use in grinding flour, water-power was also applied to pounding grain,[60][61][62] crushing ore,[63] sawing stones[64] and possibly fulling and bellows for iron furnaces.

The form of each letter and the spacing between them was carefully designed for maximum clarity and simplicity, without any decorative flourishes, emphasizing the Roman taste for restraint and order.

Today, the concrete has worn from the spaces around the stones, giving the impression of a very bumpy road, but the original practice was to produce a surface that was much closer to being flat.

The Romans constructed numerous aqueducts in order to bring water from distant sources into their cities and towns, supplying public baths, latrines, fountains and private households.

Cities and municipalities throughout the Roman Empire emulated this model and funded aqueducts as objects of public interest and civic pride, "an expensive yet necessary luxury to which all could, and did, aspire.

Freshwater reservoirs were commonly set up at the termini of aqueducts and their branch lines, supplying urban households, agricultural estates, imperial palaces, thermae or naval bases of the Roman navy.

On his return from campaigns in Greece, the general Sulla brought back what is probably the best-known element of the early imperial period: the mosaic, a decoration made of colourful chips of stone inserted into cement.

Opus vermiculatum used tiny tesserae, typically cubes of 4 millimeters or less, and was produced in workshops in relatively small panels, which were transported to the site glued to some temporary support.

[114] Their potential was fully realized in the Roman period, which saw trussed roofs over 30 meters wide spanning the rectangular spaces of monumental public buildings such as temples, basilicas, and later churches.

Although the oldest example dates to the 5th century BC,[116] it was only in the wake of the influential design of Trajan's Column that this space-saving new type permanently caught hold in Roman architecture.

[117] Apart from the triumphal columns in the imperial cities of Rome and Constantinople, other types of buildings such as temples, thermae, basilicas and tombs were also fitted with spiral stairways.

The basic plan consisted of a central forum with city services, surrounded by a compact, rectilinear grid of streets, and wrapped in a wall for defense.