Architecture of the medieval cathedrals of England

The medieval cathedrals of England, which date from between approximately 1040 and 1540, are a group of twenty-six buildings that constitute a major aspect of the country's artistic heritage and are among the most significant material symbols of Christianity.

As cathedrals, each of these buildings serves as central church for an administrative region (or diocese) and houses the throne of a bishop (Late Latin ecclēsia cathedrālis, from the Greek, καθέδρα).

[4] One of the points of interest of the English cathedrals is the way in which much of the history of medieval architecture can be demonstrated within a single building, which typically has important parts constructed in several different centuries with no attempt whatsoever to make the later work match or follow through on an earlier plan.

In 597 Pope Gregory sent Augustine as a missionary from Rome to Canterbury where a church was established and run initially by secular canons, then Benedictine monks from the late Saxon period until 1540.

Although all cathedrals gathered donations from worshippers and pilgrims; in practice major building campaigns were largely, or entirely, funded from the accumulated wealth of the bishop and the chapter clergy.

The possession of the relics of a popular saint was a source of funds to the individual church as the faithful made donations and benefices in the hope that they might receive spiritual aid, a blessing or a healing from the presence of the physical remains of the holy person.

A growing awareness of the value of England's medieval heritage had begun in the late 18th century, leading to some work on a number of the cathedrals by the architect James Wyatt.

In this part of the church are often located the tombs of former bishops, typically arranged either side of the major shrine, so the worshipping congregation symbolically comprised the whole body of clergy of the diocese, both living and dead, in communion with their patron saint.

The choir is sometimes divided from the nave of the cathedral by a wide late medieval pulpitum screen constructed of stone and in some instances carrying a large pipe organ,[4] notably at Exeter, Gloucester, Lincoln, Norwich, Rochester, St Albans, Southwell, Wells and York.

The elaborate wooden font-covers, raised by ropes and pulleys when the font was needed, that most acquired in the later Middle Ages were a favourite target of Protestant iconclasts, and rarely survive.

By comparison, the largest cathedrals of Northern France, Notre Dame de Paris, Amiens, Rouen, Reims and Chartres, are all about 135–140 metres in length, as is Cologne in Germany.

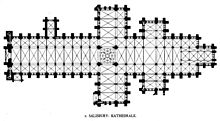

[5] The typical arrangement for an English Gothic east end is square, and may be an unbroken cliff-like design as at York, Lincoln, Ripon, Ely and Carlisle or may have a projecting Lady Chapel of which there is a great diversity as at Salisbury, Lichfield, Hereford, Exeter and Chichester.

This is particularly the case at Wells where, unlike most Gothic buildings, there are no vertical shafts that continue from the arcade to the vault and there is a very strong emphasis on the triforium gallery with its seemingly endless and undifferentiated row of narrow arches.

The Norman architecture is distinguished by its round-headed arches, and bold tiers of arcades on piers, which originally supported flat wooden roofs of which two survive, at Peterborough and Ely.

Many cathedrals have important parts in the Geometric style of the mid 13th to early 14th centuries, including much of Lincoln, Lichfield, the choir of Ely, and the chapter houses of Salisbury and Southwell.

[44] Further development included the repetition of Curvilinear or flame-like forms that occur in a great number of windows of around 1320, notably in the retro-choir at Wells and the nave of Exeter Cathedral.

[2][4] In the 1330s, when the architects of Europe were embracing the Flamboyant style, English architecture moved away from the Flowing Decorated in an entirely different and much more sober direction with the reconstruction, in highly modular form, of the choir of the Norman abbey, now cathedral, at Gloucester.

The Perpendicular style, which relies on a network of intersecting mullions and transoms rather than on a diversity of richly carved forms for effect, gives an overall impression of great unity, in which the structure of the vast windows of both clerestory and east end are integrated with the arcades below and the vault above.

[45] During the 15th century, many of England's finest towers were either built or extended in the Perpendicular style including those of the cathedrals of Gloucester, Worcester, Wells, York, Durham and Canterbury, and the spires of Chichester and Norwich.

In a still more elaborate form with stone pendants it was used to roof the Norman choir at Oxford and in the great funerary chapel of Henry VII at Westminster Abbey, at a time when Italy had embraced the Renaissance.

The façade, huge cloister and polygonal chapter house were then constructed by Richard Mason and were completed by about 1280, the later work employing Geometric Decorated tracery in the openings of windows and arcades.

The earliest part of the building at Worcester is the multi-columned Norman crypt with cushion capitals remaining from the original monastic church begun by St Wulfstan in 1084.

It is famous for the Norman crypt with sculptured capitals, the east end of 1175–84 by William of Sens, the 12th- and 13th-century stained glass, the "supremely beautiful" Perpendicular nave of 1379–1405 by Henry Yevele,[48] the fan vault of the tower of 1505 by John Wastell, the tomb of the Black Prince and the site of the murder of St. Thomas Becket.

Its most significant feature is its nine-light Flowing Decorated east window of 1322, still containing medieval glass in its upper sections, forming a "glorious termination to the choir"[4] and regarded by many as having the finest tracery in England.

[4][23] Built between 1093 and 1490, Durham Cathedral, with the exception of the upper parts of its towers, the eastern extension known as the Chapel of Nine Altars, and the large west window of 1341, is entirely Norman and is regarded by Alec Clifton-Taylor as "the incomparable masterpiece of Romanesque architecture".

Double aisles give it the widest nave of any English cathedral (115 feet); and it also has the richest set of late medieval choir stalls and misericords (1505-09) in the country.

[52] Built between 1096 and 1536, Norwich Cathedral has a Norman form, retaining the greater part of its original stone structure, which was then vaulted between 1416 and 1472 in a spectacular manner with hundreds of ornately carved, painted, and gilded bosses.

Its fame lies in its harmonious proportions, particularly from the exterior where the massing of the various horizontal parts in contrast to the vertical of the spire make it one of the most famous architectural compositions of the Medieval period.

Canon Smethurst wrote "It symbolises the peaceful loveliness of the English countryside..., the eternal truths of the Christian faith expressed in stone..."[4][23][54] Built between 1220 and 1420, Southwark Cathedral had its nave demolished and rebuilt in the late 19th century by Arthur Blomfield.

Architectural details, such as window tracery designs, were not executed as scale drawings, but were incised full-size onto a large flat gypsum tracing-floor, examples of which survive at York and Wells.