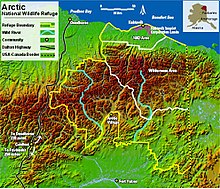

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

For thousands of years, the Gwich'in have called the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge "Iizhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit" (The Sacred Place Where Life Begins).

[2] Climate change is rapidly affecting the Arctic region, with melting polar ice caps leading to rising sea levels and warming due to the albedo effect.

In 1929, a 28-year-old forester named Bob Marshall visited the upper Koyukuk River and the central Brooks Range on his summer vacation "in what seemed on the map to be the most unknown section of Alaska.

"[4] In 1953, an article was published in the journal of the Sierra Club by then National Park Service planner George Collins and biologist Lowell Sumner titled "Northeast Alaska: The Last Great Wilderness".

In 1954, the National Park Service recommended that the untouched areas in the Northeastern region of Alaska be preserved for research and protection of nature.

In 1956, Olaus and Mardy Murie led an expedition to the Brooks Range in northeast Alaska, where they dedicated an entire summer to studying the land and wildlife ecosystems of the Upper Sheenjek Valley.

Founding the Alaska Conservation Society in 1960, Celia worked tirelessly to garner support for the protection of Alaskan wilderness ecosystems.

The remaining 10.1 million acres (41,000 km2) of the refuge are designated as "minimal management," a category intended to maintain existing natural conditions and resource values.

[17] A popular wilderness route and historic passage exists between the two villages, traversing the refuge and all its ecosystems from boreal, interior forest to Arctic Ocean coast.

In the United States, the geographic location most remote from human trails, roads, or settlements is found here, at the headwaters of the Sheenjek River.

During the Northern Hemisphere's winter months, the Arctic experiences cold and darkness which makes it one of the unique places on Earth.

Coastal lands and sea ice are used by caribou seeking relief from biting insects during summer, and by polar bears hunting seals and giving birth in snow dens during winter.

This area of rolling hills, small lakes, and north-flowing, braided rivers is dominated by tundra vegetation consisting of low shrubs, sedges, and mosses.

Beginning as predominantly treeless tundra with scattered islands of black and white spruce trees, the forest becomes progressively denser as the foothills yield to the expansive flats north of the Yukon River.

For Republicans to enable exploitation of the oil, they would need 51 votes in the Senate to pass the House bill that cannot include the ANWR drilling language.

[citation needed] People who oppose the drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge believe that it would be a threat to the lives of indigenous tribes.

In December 2017, Congress passed the Trump administration's tax bill which included a provision introduced by Senator Lisa Murkowski that required Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke to approve at least two lease sales for drilling in the refuge.

[23][24] In September 2019, the administration said they would like to see the entire coastal plain opened for gas and oil exploration, the most aggressive of the suggested development options.

The Interior Department's Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has filed a final environmental impact statement and plans to start granting leases by the end of the year.

Fish and Wildlife Service said the BLM's final statement underestimated the climate impacts of the oil leases because they viewed global warming as cyclical rather than human-made.

The administration's plan calls for "the construction of as many as four places for airstrips and well pads, 175 miles [282 km] of roads, vertical supports for pipelines, a seawater-treatment plant and a barge landing and storage site.

On August 17, 2020, Interior Secretary David Bernhardt announced an oil and gas leasing program in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

[30] On January 20, 2021, newly inaugurated President Joe Biden issued an executive order to temporarily halt drilling activity in the refuge.

[35] On January 20, 2025, President Trump declared the protected wildlife refuge open for gas and oil exploration and exploitation via executive action on his first day in office.

Researchers at Oxford University explained that increasing temperatures, melting glaciers, thawing permafrost, and rising sea levels are all indications of warming throughout the Arctic.

[40] This area for possible future oil drilling on the coastal plains of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, encompasses much of the Porcupine caribou calving grounds.

River mouths and calving glaciers, are continually moving ocean currents contribute to a unique marine ecosystem in the Arctic.

The cold, circulating water is rich in minerals, as well as the microscopic organisms (such as phytoplankton and algae) that need them to grow.

Marine mammals in the Arctic are experiencing severe impacts, including effects on migration, from disturbances such as noises from industrial activity, offshore seismic oil exploration, and well drilling.

[47] Kaktovik is an Inupiaq village of about 250 current residents located within the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge along the Beaufort Sea.