Arctic sea ice decline

It is plausible that sea ice decline also makes the jet stream weaker, which would cause more persistent and extreme weather in mid-latitudes.

Both the disappearance of sea ice and the resulting possibility of more human activity in the Arctic Ocean pose a risk to local wildlife such as polar bears.

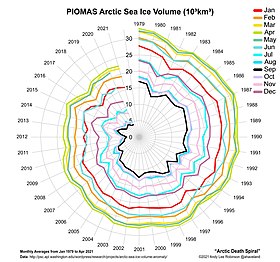

[14] Typical data visualizations for Arctic sea ice include average monthly measurements or graphs for the annual minimum or maximum extent, as shown in the adjacent images.

[19] Scientists recently measured sixteen-foot (five-meter) wave heights during a storm in the Beaufort Sea in mid-August until late October 2012.

That warm pulse quickly dissipated, but it was followed by a series of intense North Atlantic cyclones that sent very mild air poleward, in tandem with a strongly negative Arctic oscillation during the first three weeks of the month.

[25] Subsequent work with the satellite passive-microwave data indicates that from late October 1978 through the end of 1996 the extent of Arctic sea ice decreased by 2.9% per decade.

[32] Estimating the exact year when the Arctic Ocean will become "ice-free" is very difficult, due to the large role of interannual variability in sea ice trends.

Thus, they advocated for the use of expert judgement in addition to models to help predict ice-free Arctic events, but they noted that expert judgement could also be done in two different ways: directly extrapolating ice loss trends (which would suggest an ice-free Arctic in 2020) or assuming a slower decline trend punctuated by the occasional "big melt" seasons (such as those of 2007 and 2012) which pushes back the date to 2028 or further into 2030s, depending on the starting assumptions about the timing and the extent of the next "big melt".

[35] A 2009 paper from Muyin Wang and James E. Overland applied observational constraints to the projections from six CMIP3 climate models and estimated nearly ice-free Arctic Ocean around September 2037, with a chance it could happen as early as 2028.

[37] In 2009, a study using 18 CMIP3 climate models found that they project ice-free Arctic a little before 2100 under a scenario of medium future greenhouse gas emissions.

[32] The Third U.S. National Climate Assessment (NCA), released May 6, 2014, reported that the Arctic Ocean is expected to be ice free in summer before mid-century.

[7]: 1247–1251 A paper published in 2021 shows that the CMIP6 models which perform the best at simulating Arcic sea ice trends project the first ice-free conditions around 2035 under SSP5-8.5, which is the scenario of continually accelerating greenhouse gas emissions.

Its bright shiny surface reflects sunlight during the Arctic summer; dark ocean surface exposed by the melting ice absorbs more sunlight and becomes warmer, which increases the total ocean heat content and helps to drive further sea ice loss during the melting season, as well as potentially delaying its recovery during the polar night.

Arctic ice decline between 1979 and 2011 is estimated to have been responsible for as much radiative forcing as a quarter of CO2 emissions the same period,[45] which is equivalent to around 10% of the cumulative CO2 increase since the start of the Industrial Revolution.

[48] In 2021, the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report said with high confidence that there is no hysteresis and no tipping point in the loss of Arctic summer sea ice.

Specifically, thinner sea ice leads to increased heat loss in the winter, creating a negative feedback loop.

However, higher levels of global warming would delay the recovery from ice-free episodes and make them occur more often and earlier in the summer.

[51] This rapid warming also makes it easier to detect any potential connections between the state of sea ice and weather conditions elsewhere than in any other area.

[64] There are also potential links to summer precipitation:[65] a connection has been proposed between the reduced BKS ice extent in November–December and greater June rainfall over South China.

Autumn sea ice decline of one standard deviation in that region would reduce mean spring temperature over central Russia by nearly 0.8 °C, while increasing the probability of cold anomalies by nearly a third.

[74] One of the researchers noted, "The expectation is that with further sea ice decline, temperatures in the Arctic will continue to rise, and so will methane emissions from northern wetlands.

This absorption leads to more mercury, a toxin, entering the food chain where it can negatively affect fish and the animals and people who consume them.

[81][82] An early study by James Hansen and colleagues suggested in 1981 that a warming of 5 to 10 °C, which they expected as the range of Arctic temperature change corresponding to doubled CO2 concentrations, could open the Northwest Passage.

[90] Polar bears are turning to alternative food sources because Arctic sea ice melts earlier and freezes later each year.

[91] As a result, the diet is less nutritional, which leads to reduced body size and reproduction, thus indicating population decline in polar bears.