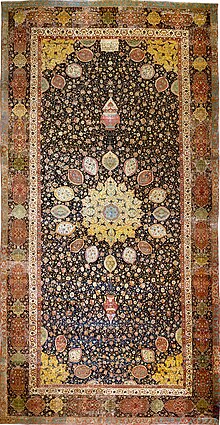

Ardabil Carpet

Such medallions and shapes were central to the design and reality of Persian gardens, a common symbol of paradise for followers of Islam.

[7] The inscription reads:I have no refuge in the world other than thy threshold.There is no protection for my head other than this door.The work of the servant of the threshold Maqsud of Kashan in the year 946.

However, a debate exists due to the fact that there is no proof that graphical perspective was used in 1530s Iran and other historians and critics instead believe the lamps are ones found in mosques or shrines at the time.

The design of these carpets are not typical of later Ardabil rugs, but products of the finest Safavid weaving, with influence from manuscript painting.

On the other hand, at their presumed original size, the two would fit into a space in the more important Imam Reza Shrine at Mashad.

When the Victoria and Albert Museum began to check out the piece in 1914, the historical consensus came to be that the modifications on the current Los Angeles Ardabil to repair the London Ardabil were managed by Ziegler and Company, the first buyer of the carpets from Persian resident Hildebrand Stevens, supposedly using Tabriz or Turkish craftsmen.

Historians of the time spoke to this, stating 'The highest market value was for complete carpets, rather than damaged ones or fragments.

[8] The second "secret" carpet, smaller, now borderless and with some of the field missing, made up from the remaining usable sections, was sold to the American businessmen Clarence Mackay and was exchanged by wealthy buyers for years.

Passing through the Mackay, Yerkes, and De la Mare art collections, it was eventually revealed and shown in 1931 at an exhibition in London.

Getty was approached by agents on behalf of King Farouk of Egypt who offered $250,000 so that it could be given as a wedding present to his sister and the Shah of Iran.