Cochineal

Carmine dye was used in the Americas for coloring fabrics and became an important export good in the 16th century during the colonial period.

Fears over the safety of artificial food additives renewed the popularity of cochineal dyes, and the increased demand has made cultivation of the insect profitable again,[3] with Peru being the largest producer, followed by Mexico, Chile, Argentina and the Canary Islands.

The nymphs secrete a waxy white substance over their bodies for protection from water loss and excessive sun.

Later, they move to the edge of the cactus pad, where the wind catches the wax filaments and carries the insects to a new host.

[14] D. coccus has only been noted on Opuntia species, including O. amyclaea, O. atropes, O. cantabrigiensis, O. brasilienis, O. ficus-indica, O. fuliginosa, O. jaliscana, O. leucotricha, O. lindheimeri, O. microdasys, O. megacantha, O. pilifera, O. robusta, O. sarca, O. schikendantzii, O. stricta, O. streptacantha, and O.

Insects and their larvae such as pyralid moths (order Lepidoptera), which destroy the cactus, and predators such as lady bugs (Coleoptera), various Diptera (such as Syrphidae and Chamaemyiidae), lacewings (Neuroptera), and ants (Hymenoptera) have been identified, as well as numerous parasitic wasps.

For large-scale cultivation, advanced pest control methods have to be developed, including alternative bioinsecticides or traps with pheromones.

[3] Opuntia species, known commonly as prickly pears, were first brought to Australia in an attempt to start a cochineal dye industry in 1788.

Captain Arthur Phillip collected a number of cochineal-infested plants from Brazil on his way to establish the first European settlement at Botany Bay, part of which is now Sydney, New South Wales.

[18] The attempt was a failure in two ways: the Brazilian cochineal insects soon died off, but the cacti thrived, eventually overrunning about 100,000 sq mi (259,000 km2) of eastern Australia.

[19] The cacti were eventually brought under control in the 1920s by the deliberate introduction of a South American moth, Cactoblastis cactorum, the larvae of which feed on the cactus.

[citation needed] A conflict of interest among communities led to closure of the cochineal business in Ethiopia, but the insect spread and became a pest.

[20] There has been a population of Dactylopius insects on prickly pear cactuses around Cuyler Manor in Uitenhage; several cochineal species were introduced to South Africa[when?

[28]: 12–20 Eleven cities conquered by Moctezuma II in the 15th century paid a yearly tribute of 2000 decorated cotton blankets and 40 bags of cochineal dye each.

Furthermore, the process of layering the various hues of the same pigment on top of each other enabled the Aztec artists to create variations in the intensity of the subject matter.

They all become brownish and ultimately almost disappear after a short exposure to sunlight or the more prolonged attack of strong diffused daylight", Arthur Herbert Church[37][40]In Europe, there was no comparable red dye or pigment.

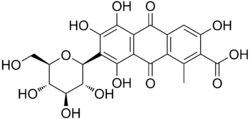

Its key ingredient, kermesic acid, was also extracted from an insect, Kermes vermilio, which lives on Quercus coccifera oaks native to the Near East, and the European side of the Mediterranean Basin.

It provided the most intense color and it set more firmly on woolen garments compared to clothes made of materials of pre-Hispanic origin such as cotton or agave and yucca fibers.

[44] The dyestuff was used throughout Europe and was so highly prized, its price was regularly quoted on the London and Amsterdam Commodity Exchanges (with the latter one beginning to record it in 1589).

[citation needed] During the colonial period in Latin America, many indigenous communities produced cochineal under a type of contract known as Repartimiento de Mercancías.

This was a type of "contract forwarding" agreement, in which a trader lent money to producers in advance, with a "call option" to buy the product once it was harvested.

Communities with a history of cochineal production and export have been found to have lower poverty rates and higher female literacy, but also smaller indigenous populations.

[47] In 1777, French botanist Nicolas-Joseph Thiéry de Menonville, presenting himself as a botanizing physician, smuggled the insects and pads of the Opuntia cactus to Saint Domingue.

[44] The delicate manual labour required for the breeding of the insect could not compete with the modern methods of the new industry, and even less so with the lowering of production costs.

The "tuna blood" dye (from the Mexican name for the Opuntia fruit) stopped being used and trade in cochineal almost totally disappeared in the course of the 20th century.

[54] Natural carmine dye used in food and cosmetics can render the product unacceptable to vegetarian or vegan consumers.

[58] A significant proportion of the insoluble carmine pigment produced is used in the cosmetics industry for hair- and skin-care products, lipsticks, face powders, rouges, and blushes.

[59][28] Some towns in the Mexican state of Oaxaca continue to follow traditional practices of producing and using cochineal when making handmade textiles.

[60] In Guatemala, Heifer International has partnered with local women who wished to reintroduce traditional artisanal practices of cochineal production and use.

[4][63] In spite of the widespread use of carmine-based dyes in food and cosmetic products, a small number of people have been found to experience occupational asthma, food allergy and cosmetic allergies (such as allergic rhinitis and cheilitis), IgE-mediated respiratory hypersensitivity, and in rare cases anaphylactic shock.