Areography

In April 2023, The New York Times reported an updated global map of Mars based on images from the Hope spacecraft.

The history of these observations are marked by the oppositions of Mars, when the planet is closest to Earth and hence is most easily visible, which occur every couple of years.

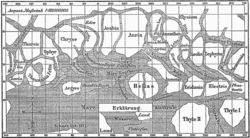

These canali were supposedly long straight lines on the surface of Mars to which he gave names of famous rivers on Earth.

Today, the United States Geological Survey defines thirty cartographic quadrangles for the surface of Mars.

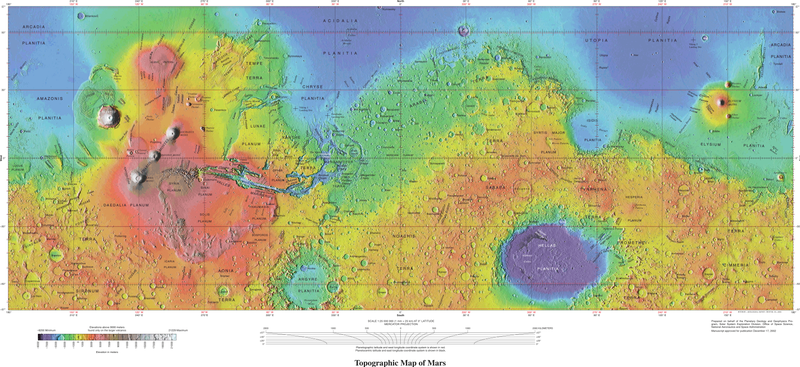

[10] In 2001, Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter data led to a new convention of zero elevation defined as the equipotential surface (gravitational plus rotational) whose average value at the equator is equal to the mean radius of the planet.

[12] Mars's equator is defined by its rotation, but the location of its prime meridian was specified, as is Earth's, by choice of an arbitrary point which later observers accepted.

In 1877, their choice was adopted as the prime meridian by the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli when he began work on his notable maps of Mars.

[13][14] After the Mariner spacecraft provided extensive imagery of Mars, in 1972 the Mariner 9 Geodesy / Cartography Group proposed that the prime meridian pass through the center of a small 500 m diameter crater, named Airy-0, located in Sinus Meridiani along the meridian line of Beer and Mädler, thus defining 0.0° longitude with a precision of 0.001°.

The dichotomy of Martian topography is striking: northern plains flattened by lava flows contrast with the southern highlands, pitted and cratered by ancient impacts.

In comparison, the difference between Earth's highest and lowest points (Mount Everest and the Mariana Trench) is only 19.7 km.

The International Astronomical Union's Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature is responsible for naming Martian surface features.

[19][20][21] The northern lowlands comprise about one-third of the surface of Mars and are relatively flat, with occasional impact craters.

[19] Both impact-related hypotheses involve processes that could have occurred before the end of the primordial bombardment, implying that the crustal dichotomy has its origins early in the history of Mars.

Using geologic data, researchers found support for the single impact of a large object hitting Mars at approximately a 45-degree angle.

Additional evidence analyzing Martian rock chemistry for post-impact upwelling of mantle material would further support the giant impact theory.

Rather than giving names to the various markings they mapped, Beer and Mädler simply designated them with letters; Meridian Bay (Sinus Meridiani) was thus feature "a".

Over the next twenty years or so, as instruments improved and the number of observers also increased, various Martian features acquired a hodge-podge of names.

To give a couple of examples, Solis Lacus was known as the "Oculus" (the Eye), and Syrtis Major was usually known as the "Hourglass Sea" or the "Scorpion".

Proctor explained his system of nomenclature by saying, "I have applied to the different features the names of those observers who have studied the physical peculiarities presented by Mars."