Argumentation theory

With historical origins in logic, dialectic, and rhetoric, argumentation theory includes the arts and sciences of civil debate, dialogue, conversation, and persuasion.

[3] It also encompasses eristic dialog, the branch of social debate in which victory over an opponent is the primary goal, and didactic dialogue used for teaching.

Also, argumentation scholars study the post hoc rationalizations by which organizational actors try to justify decisions they have made irrationally.

[7] One of the original contributors to this trend was the philosopher Chaïm Perelman, who together with Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca introduced the French term la nouvelle rhetorique in 1958 to describe an approach to argument which is not reduced to application of formal rules of inference.

Perelman's view of argumentation is much closer to a juridical one, in which rules for presenting evidence and rebuttals play an important role.

In this new hybrid approach argumentation is used with or without empirical evidence to establish convincing conclusions about issues which are moral, scientific, epistemic, or of a nature in which science alone cannot answer.

In general, the label "argumentation" is used by communication scholars such as (to name only a few) Wayne E. Brockriede, Douglas Ehninger, Joseph W. Wenzel, Richard Rieke, Gordon Mitchell, Carol Winkler, Eric Gander, Dennis S. Gouran, Daniel J. O'Keefe, Mark Aakhus, Bruce Gronbeck, James Klumpp, G. Thomas Goodnight, Robin Rowland, Dale Hample, C. Scott Jacobs, Sally Jackson, David Zarefsky, and Charles Arthur Willard, while the term "informal logic" is preferred by philosophers, stemming from University of Windsor philosophers Ralph H. Johnson and J. Anthony Blair.

Inspired by ethnomethodology, it was developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s principally by the sociologist Harvey Sacks and, among others, his close associates Emanuel Schegloff and Gail Jefferson.

Sacks died early in his career, but his work was championed by others in his field, and CA has now become an established force in sociology, anthropology, linguistics, speech-communication and psychology.

Recently CA techniques of sequential analysis have been employed by phoneticians to explore the fine phonetic details of speech.

Empirical studies and theoretical formulations by Sally Jackson and Scott Jacobs, and several generations of their students, have described argumentation as a form of managing conversational disagreement within communication contexts and systems that naturally prefer agreement.

Perhaps the most radical statement of the social grounds of scientific knowledge appears in Alan G.Gross's The Rhetoric of Science (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990).

Interpretive argumentation is pertinent to the humanities, hermeneutics, literary theory, linguistics, semantics, pragmatics, semiotics, analytic philosophy and aesthetics.

It is possible for a media sound-bite or campaign flier to present a political position for the incumbent candidate that completely contradicts the legislative action taken in the Capitol on behalf of the constituents.

It may only take a small percentage of the overall voting group who base their decision on the inaccurate information to form a voter bloc large enough to swing an overall election result.

Savvy Political consultants will take advantage of low-information voters and sway their votes with disinformation and fake news because it can be easier and sufficiently effective.

Thus smokers think that they personally will avoid cancer, promiscuous people practice unsafe sex, and teenagers drive recklessly.

[19] Similarly, G. Thomas Goodnight has studied "spheres" of argument and sparked a large literature created by younger scholars responding to or using his ideas.

By contrast, Toulmin contends that many of these so-called standard principles are irrelevant to real situations encountered by human beings in daily life.

In Human Understanding (1972), Toulmin suggests that anthropologists have been tempted to side with relativists because they have noticed the influence of cultural variations on rational arguments.

In other words, the anthropologist or relativist overemphasizes the importance of the "field-dependent" aspect of arguments, and neglects or is unaware of the "field-invariant" elements.

In order to provide solutions to the problems of absolutism and relativism, Toulmin attempts throughout his work to develop standards that are neither absolutist nor relativist for assessing the worth of ideas.

In Cosmopolis (1990), he traces philosophers' "quest for certainty" back to René Descartes and Thomas Hobbes, and lauds John Dewey, Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger, and Richard Rorty for abandoning that tradition.

Toulmin did not realize that this layout could be applicable to the field of rhetoric and communication until his works were introduced to rhetoricians by Wayne Brockriede and Douglas Ehninger.

In this book, Toulmin attacks Thomas Kuhn's account of conceptual change in his seminal work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962).

Frans H. van Eemeren, the late Rob Grootendorst, and many of their students and co-authors have produced a large body of work expounding this idea.

The dialectical conception of reasonableness is given by ten rules for critical discussion, all being instrumental for achieving a resolution of the difference of opinion (from Van Eemeren, Grootendorst, & Snoeck Henkemans, 2002, p. 182–183).

The model can however serve as an important heuristic and critical tool for testing how reality approximates this ideal and point to where discourse goes wrong, that is, when the rules are violated.

Walton's logical argumentation model took a view of proof and justification different from analytic philosophy's dominant epistemology, which was based on a justified true belief framework.

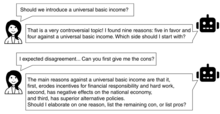

[37] Data from the collaborative structured online argumentation platform Kialo has been used to train and to evaluate natural language processing AI systems such as, most commonly, BERT and its variants.