Aristotle's views on women

Aristotle's views on women influenced later Western thinkers, who quoted him as an authority until the end of the Middle Ages.

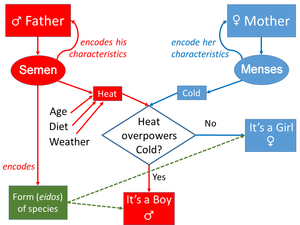

[1][2][3] Aristotle's inheritance model sought to explain how the parents' characteristics are transmitted to the child, subject to influence from the environment.

[4] The child's sex can be influenced by factors that affect temperature, including the weather, the wind direction, diet, and the father's age.

[10][11][12] Indeed, Aristotle often made clear-cut statements, as seen in works like Prior Analytics 1.2-3.25alff-25b1ff, 1.26.43b32ff, and frequently mentioned women.

In some segments, he does express that women are naturally inferior and ought to be governed, consistently within the household and in the optimal state.

Additionally, when discussing the ideal citizen, he frequently employs the term aner, meaning "man" (Politics 1259b2-4; 3.4.1276b16ff, 1277b18ff; Rhetoric 1.9.1367a16-18; Eudemian Ethics 7.2.1237a4-6).

In the Generation of Animals (2.1.732a3-10), Aristotle argues that while a man's semen imparts the superior form, a woman's menstrual fluid provides the inferior matter to the formation of a fetus.

[13] He describes women as mathimatikoteron, meaning they have a heightened capacity for rational learning; phrontistikotera, indicating they are more thoughtful in child-rearing; and mnemonikoteron, highlighting their superior memory.

The intellectual strengths in which women excel, notably their ability to strategize, learn, remember, and rear children, are linked to the virtue of prudence, which is especially crucial for lawmakers focused on the nurturing of the young (Politics 8.1.1337a11).

On the topic of motherhood, when Aristotle discusses citizenship, he doesn't explicitly say or hint that he excludes women from political life.

He could also categorically group mothers alongside others he deems as citizens in a limited or nominal sense, like underage children.