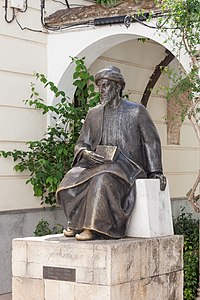

Maimonides

He was born on Passover eve 1138 or 1135,[d] and lived in Córdoba in al-Andalus (now in Spain) within the Almoravid Empire until his family was expelled for refusing to convert to Islam.

[13] Maimonides was born 1138 (or 1135) in Córdoba in the Muslim-ruled Almoravid Caliphate, at the end of the golden age of Jewish culture in the Iberian Peninsula after the first centuries of Muslim rule.

[17] A Berber dynasty, the Almohads, conquered Córdoba in 1148 and abolished dhimmi status (i.e., state protection of non-Muslims ensured through payment of a tax, the jizya) in some[which?]

[23] Maimonides shortly thereafter was instrumental in helping rescue Jews taken captive during the Christian Amalric of Jerusalem's siege of the southeastern Nile Delta town of Bilbeis.

[24] Following this success, the Maimonides family, hoping to increase their wealth, gave their savings to his brother, the youngest son David ben Maimon, a merchant.

In a letter discovered in the Cairo Geniza, he wrote: The greatest misfortune that has befallen me during my entire life—worse than anything else—was the demise of the saint, may his memory be blessed, who drowned in the Indian sea, carrying much money belonging to me, to him, and to others, and left with me a little daughter and a widow.

On the day I received that terrible news I fell ill and remained in bed for about a year, suffering from a sore boil, fever, and depression, and was almost given up.

A work known as "Megillat Zutta" was written by Abraham ben Hillel, who writes a scathing description of Sar Shalom while praising Maimonides as "the light of east and west and unique master and marvel of the generation.

[29] In his medical writings, Maimonides described many conditions, including asthma, diabetes, hepatitis, and pneumonia, and he emphasized moderation and a healthy lifestyle.

[32] Although he frequently wrote of his longing for solitude in order to come closer to God and to extend his reflections—elements considered essential in his philosophy to the prophetic experience—he gave over most of his time to caring for others.

After visiting the Sultan's palace, he would arrive home exhausted and hungry, where "I would find the antechambers filled with gentiles and Jews [...] I would go to heal them, and write prescriptions for their illnesses [...] until the evening [...] and I would be extremely weak.

A variety of medieval sources beginning with Al-Qifti maintain that his body was interred near Lake Tiberias, though there is no contemporary evidence for his removal from Egypt.

They altered his gravestone, which previously had been inscribed 'choicest of the human race (מבחר המין האנושי)', so that instead it read 'the excommunicated heretic (מוחרם ומין)'.

But later, after the provocateurs had repented of their act, and praised this great man, a student repaired the gravestone to read 'choicest of the Israelites (מבחר המין הישראלי)'".

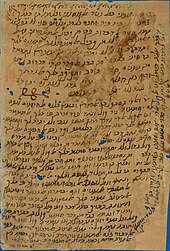

The work gathers all the binding laws from the Talmud, and incorporates the positions of the Geonim (post-Talmudic early Medieval scholars, mainly from Mesopotamia).

One of his more important medical works is his Guide to Good Health (Regimen Sanitatis), which he composed in Arabic for the Sultan al-Afdal, son of Saladin, who suffered from depression.

[62] The Treatise on Logic (Arabic: Maqala Fi-Sinat Al-Mantiq) has been printed 17 times, including editions in Latin (1527), German (1805, 1822, 1833, 1828), French (1936) by Moïse Ventura and in 1996 by Rémi Brague, and English (1938) by Israel Efros, and in an abridged Hebrew form.

These principles were controversial when first proposed, evoking criticism by Rabbis Hasdai Crescas and Joseph Albo, and were effectively ignored by much of the Jewish community for the next few centuries.

[75] The principle that inspired his philosophical activity was identical to a fundamental tenet of scholasticism: there can be no contradiction between the truths which God has revealed and the findings of the human mind in science and philosophy.

He claimed that in order to understand how to know God, every human being must, by study, and meditation attain the degree of perfection required to reach the prophetic state.

Despite his rationalistic approach, he does not explicitly reject the previous ideas (as portrayed, for example, by Rabbi Yehuda Halevi in his Kuzari) that in order to become a prophet, God must intervene.

Man, he reasons, is too insignificant a figure in God's myriad works to be their primary characterizing force, and so when people see mostly evil in their lives, they are not taking into account the extent of positive Creation outside of themselves.

The first type of evil Maimonides states is the rarest form, but arguably of the most necessary—the balance of life and death in both the human and animal worlds itself, he recognizes, is essential to God's plan.

Maimonides conceived of an eight-level hierarchy of tzedakah, where the highest form is to give a gift, loan, or partnership that will result in the recipient becoming self-sufficient instead of living upon others.

[91] The eight levels are:[92] Perhaps one of Maimonides' most highly acclaimed and renowned writings is his treatise on the Messianic era, written originally in Judeo-Arabic and which he elaborates on in great detail in his Commentary on the Mishnah (Introduction to the 10th chapter of tractate Sanhedrin, also known as Pereḳ Ḥeleḳ).

Rather, divine interaction is by way of angels, whom Maimonides often regards to be metaphors for the laws of nature, the principles by which the physical universe operates, or Platonic eternal forms.

Maimonides distinguishes two kinds of intelligence in man, the one material in the sense of being dependent on, and influenced by, the body, and the other immaterial, that is, independent of the bodily organism.

The first to compile a comprehensive lexicon containing an alphabetically arranged list of difficult words found in Maimonides' Mishneh Torah was Tanḥum ha-Yerushalmi (1220–1291).

[102] Some more acculturated Jews in the century that followed his death, particularly in Spain, sought to apply Maimonides' Aristotelianism in ways that undercut traditionalist belief and observance, giving rise to an intellectual controversy in Spanish and southern French Jewish circles.

Crescas bucked the eclectic trend, by demolishing the certainty of the Aristotelian world-view, not only in religious matters but also in the most basic areas of medieval science (such as physics and geometry).