Armagh rail disaster

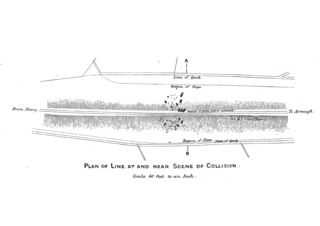

The rear portion was inadequately braked and ran back down the gradient, colliding with a following train.

At the time, the disaster led directly to various safety measures becoming legal requirements for railways in the United Kingdom.

Armagh Methodist Sunday School had organised a day trip to the seaside resort of Warrenpoint, County Down, a distance of about 24 miles (39 km).

A special Great Northern Railway of Ireland (GNR(I)) train was arranged for the journey, intended to carry about eight hundred passengers.

[4] Asked to provide rolling stock for a special train to take 800 excursionists, the locomotive department at Dundalk sent fifteen vehicles hauled by a 'four-coupled'[note 2] (2-4-0) locomotive;[note 3] however, the instructions to the engine driver, Thomas McGrath, were that the train was to be of thirteen vehicles.

There were more intending passengers than anticipated and, to accommodate the excursion, the Armagh station master decided to use all fifteen vehicles.

According to the driver: The station-master replied "I did not write those instructions for you"; I said "Mr. Cowan [the company's general manager] wrote them."

It was overcome by the weight of ten vehicles, and the rear portion began to move downhill and gathered speed down the steep gradient back towards Armagh Station.

[4] The pursuing driver said he did not believe they had reached more than 30 miles per hour (48 km/h);[7] the Board of Trade inspector thought 40 mph (64 km/h) a fair estimate of their speed at the collision.

A further practical trial showed that a single brake van, with the brake correctly working and correctly applied, could (without the aid of scotching) hold 10 carriages on the Armagh bank, against both their own weight and a nudge similar to that which witnesses agreed in describing as having been caused by run-back of the front portion of the divided train.

[4] The locomotive shed foreman at Dundalk was criticised for want of judgment in not sending a more experienced driver[note 13] and in his choice of engine.

The 2-4-0 supplied would have had insufficient margins (even when hauling a 13-vehicle excursion train) to be sure of maintaining a safe speed[note 14] over the more onerous gradients farther up the line.

The chief clerk came in for further criticism for not having persisted with his instructions for the regular train engine to provide assistance.

[4] There was no direct criticism of the station master; either for having increased the size of the train, or for persuading the engine driver to attempt Armagh bank without assistance.

The organisation of this was criticised on a number of points: The running of such heavily laden excursion trains as the present on lines with bad gradients, is a practice much to be deprecated; it would be far better to limit them to about 10 vehicles.

[4]The inquest was completed on Friday 21 June 1889, and made findings of culpable negligence against six of those involved; those at Dundalk responsible for selection of the engine, the driver and both guards on the train, and Mr Elliott who had taken charge.

[16][17] One guard had been injured in the crash and was presumably still in hospital; the Dundalk personnel were not charged, the 'practical trial' showing that the engine supplied should not have been defeated by Armagh bank if correctly handled having been carried out on Saturday 22 June.

The jury are not reported to have made any findings against more senior management of the Great Northern Railway of Ireland.

Elliott was tried in Dublin in August, when the jury reported they were unable to agree; on re-trial in October he was acquitted.

As the President of the Board of Trade has stated in Parliament his intention to introduce a Bill to make compulsory the adoption of automatic continuous brakes, should the report on this collision point out that it would have been avoided had the excursion train been fitted with them, it is unnecessary for me to say more upon the subject.

[4]For many years the Railway Inspectorate of the Board of Trade had been advocating three vital safety measures (among others) to often reluctant railway managements: The Board of Trade had got as far and as fast as it could by persuasion, but an inspector commented in 1880 after the Wennington Junction rail crash: It is all very well for the Midland Railway Company now to plead that they are busily employed in fitting up their passenger trains with continuous breaks, but the necessity for providing the passenger trains with a larger proportion of break power was pointed out by the Board of Trade to all Railway Companies more than 20 years since; and with the exception of a very few railway companies that recognised that necessity and acted upon it, it may be truly stated that the principal Railway Companies throughout the Kingdom have resisted the efforts of the Board of Trade to cause them to do what was right, which the latter had no legal power to enforce, and even now it will be seen by the latest returns laid before Parliament that some of those Companies are still doing nothing to supply this now generally acknowledged necessityIn the aftermath of the accident, questions to the President of the Board of Trade Sir Michael Hicks Beach revealed that More specifically, for the Great Northern of Ireland: Mr. Channing (Northamptonshire, E.): I beg to ask the President of the Board of Trade whether 11 years ago, in reporting upon a serious collision on the Great Northern of Ireland Railway, between two portions of a train which had become separated, General Hutchinson pointed out to the Company that an automatic brake would have absolutely prevented the collision, by arresting the carriages the moment the separation occurred; whether at that time the secretary of the company informed General Hutchinson that the simple vacuum brake, whose failure caused this accident, was being merely tried experimentally on the line, and that the company had not yet come to a decision as to what brake would be finally adopted; and, whether, in spite of this recommendation, this simple vacuum brake, upon the failure of which General Hutchinson reported in 1878, has remained in use on the Great Northern of Ireland line ever since, and is the same brake that was in use in the recent disastrous collision near Armagh?

[22]The government was already short of parliamentary time in which to pass legislation it was already committed to, and had promised to introduce no further controversial measures.

For that reason, some Liberal MPs sympathetic to railwaymen's concerns on working hours and the hazards of shunting[note 16] expressed disappointment that the bill did not go far enough.

I am of opinion that the lives of passengers and railway men will be safer in the long run, if these matters are left in the hands of those who understand them best.

the two men who acted as guards on the excursion train that met with the fatal disaster were untried men, shunters at Newry Station, and had no knowledge of the line or of the duties of a guard, and that one of them, Moorhead, had been on duty 16 hours the previous day, and also from four o'clock that morning, and that his wages were 11s.