Arminianism

Arminianism is a movement of Protestantism initiated in the early 17th century, based on the theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius and his historic supporters known as Remonstrants.

Dutch Arminianism was originally articulated in the Remonstrance (1610), a theological statement submitted to the States General of the Netherlands.

[6] Another key figure, Sebastian Castellio (1515–1563), who opposed Calvin's views on predestination and religious intolerance, is known to have influenced both the Mennonites and certain theologians within Arminius’s circle.

[9] He was taught by Theodore Beza, Calvin's hand-picked successor, but after examination of the scriptures, he rejected his teacher's theology that it is God who unconditionally elects some for salvation.

[11] After his death, Arminius's followers continued to advance his theological vision, crafting the Five articles of Remonstrance (1610), in which they express their points of divergence from the stricter Calvinism of the Belgic Confession.

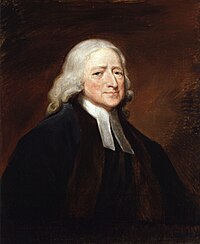

[25] Wesley defended his soteriology through the publication of a periodical titled The Arminian (1778) and in articles such as Predestination Calmly Considered.

[26] To support his stance, he strongly maintained belief in total depravity while clarifying other doctrines notably prevenient grace.

[9] His system of thought has become known as Wesleyan Arminianism, the foundations of which were laid by him and his fellow preacher John William Fletcher.

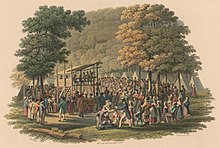

[36] During the 20th century, as Pentecostal churches began to settle and incorporate more standard forms, they started to formulate theology that was fully Arminian.

[47] The majority of Southern Baptists embrace a traditionalist form of Arminianism which includes a belief in eternal security,[48][49][50][44] though many see Calvinism as growing in acceptance.

[62] In contemporary Baptist traditions, advocates of Arminian theology include Roger E. Olson,[63] F. Leroy Forlines,[64] Robert Picirilli[65] and J. Matthew Pinson.

[79] In response, Augustine proposed a view in which God is the ultimate cause of all human actions, a stance that aligns with soft determinism.

[100][101][102] This theological system was presented by Jacobus Arminius and maintained by some of the Remonstrants, such as Simon Episcopius[103] and Hugo Grotius.

[105][106] Its core teachings are summarized in the Five Articles of Remonstrance, reflecting Arminius’s views, with some sections directly from his Declaration of Sentiments.

[119] In Arminian theology, human beings possess libertarian free will, making them the ultimate source of their choices and granting them the ability to choose otherwise.

[131] Jesus's death satisfies God's justice: The penalty for the sins of the elect is paid in full through the crucifixion of Christ.

Arminius states that "Justification, when used for the act of a Judge, is either purely the imputation of righteousness through mercy [...] or that man is justified before God [...] according to the rigor of justice without any forgiveness.

[142] Related to eschatological considerations, Jacobus Arminius[143] and the first Remonstrants, including Simon Episcopius[144] believed in everlasting fire where the wicked are thrown by God at judgment day.

But this security was not unconditional but conditional—"provided they [believers] stand prepared for the battle, implore his help, and be not wanting to themselves, Christ preserves them from falling.

[152] In his "Declaration of Sentiments" (1607), Arminius said, "I never taught that a true believer can, either totally or finally fall away from the faith, and perish; yet I will not conceal, that there are passages of scripture which seem to me to wear this aspect.

"[153] However, elsewhere Arminius expressed certainty about the possibility of falling away: In c. 1602, he noted that a person integrated into the church might resist God's work and that a believer's security rested solely in their choice not to abandon their faith.

[154][155] He argued that God's covenant did not eliminate the possibility of falling away but provided a gift of fear to keep individuals from defecting, as long as it thrived in their hearts.

[162][151][163] After the death of Arminius in 1609, his followers wrote a Remonstrance (1610) based quite literally on his Declaration of Sentiments (1607) which expressed prudence on the possibility of apostasy.

[164] Sometime between 1610 and the official proceeding of the Synod of Dort (1618), the Remonstrants became fully persuaded in their minds that the Scriptures taught that a true believer was capable of falling away from faith and perishing eternally as an unbeliever.

[180] Wesley taught that through the Holy Spirit, Christians can achieve a state of practical perfection, or "entire sanctification", characterized by a lack of voluntary sin.

[191] Arminius referred to Pelagianism as "the grand falsehood" and stated that he "must confess that I detest, from my heart, the consequences [of that theology].

[194][195] Semi-Pelagianism holds that faith begins with human will, while its continuation and fulfillment depend on God's grace,[84] giving it the label "human-initiated synergism".

[85] In contrast, both Classical and Wesleyan Arminianism affirm that prevenient grace from God initiates the process of salvation,[196][197] a view sometimes referred to as "Semi-Augustinian", or "God-initiated synergism".

[199][200] Calvinism and Arminianism, while sharing historical roots and many theological doctrines, diverge notably on the concepts of divine predestination and election.

God therefore knows the future partially in possibilities (human free actions) rather than solely certainties (divinely determined events).