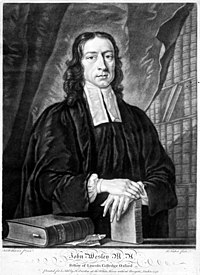

John Wesley

Moving across Great Britain and Ireland, he helped form and organise small Christian groups (societies and classes) that developed intensive and personal accountability, discipleship, and religious instruction.

Although he was not a systematic theologian, Wesley argued against Calvinism and for the notion of Christian perfection, which he cited as the reason that he felt God "raised up" Methodists into existence.

He held that, in this life, Christians could achieve a state where the love of God "reigned supreme in their hearts", giving them not only outward but inward holiness.

In his early ministry years, Wesley was barred from preaching in many parish churches and the Methodists were persecuted; he later became widely respected, and by the end of his life, was described as "the best-loved man in England".

In 1714, at age 11, Wesley was sent to the Charterhouse School in London (under the mastership of John King from 1715), where he lived the studious, methodical and, for a while, religious life in which he had been trained at home.

[10] In the year of his ordination, he read Thomas à Kempis and Jeremy Taylor, showed his interest in mysticism,[11] and began to seek the religious truths which underlay the great revival of the 18th century.

[13] During Wesley's absence, his younger brother Charles (1707–88) matriculated at Christ Church; along with two fellow students, he formed a small club for the purpose of study and the pursuit of a devout Christian life.

A list of "General Questions" which he developed in 1730 evolved into an elaborate grid by 1734 in which he recorded his daily activities hour-by-hour, resolutions he had broken or kept, and ranked his hourly "temper of devotion" on a scale of 1 to 9.

[25] Although his primary goal was to evangelise the Native American people, a shortage of clergy in the colony largely limited his ministry to European settlers in Savannah.

He hesitated to marry her because he felt that his first priority in Georgia was to be a missionary to the Native Americans, and he was interested in the practice of clerical celibacy within early Christianity.

Overcoming his scruples, he preached the first time at Whitefield's invitation a sermon in the open air, at a brickyard, near St Philip's Marsh, on 2 April 1739.

I could scarce reconcile myself to this strange way of preaching in the fields, of which he [Whitefield] set me an example on Sunday; having been all my life till very lately so tenacious of every point relating to decency and order, that I should have thought the saving of souls almost a sin if it had not been done in a church.

They were denounced as promulgators of strange doctrines, fomenters of religious disturbances; as blind fanatics, leading people astray, claiming miraculous gifts, attacking the clergy of the Church of England, and trying to re-establish Catholicism.

The prejudices of his High-church training, his strict notions of the methods and proprieties of public worship, his views of the apostolic succession and the prerogatives of the priest, even his most cherished convictions, were not allowed to stand in the way.

When the Wesleys spotted the building atop Windmill Hill, north of Finsbury Fields, the structure which previously cast brass guns and mortars for the Royal Ordnance had been sitting vacant for 23 years; it had been abandoned because of an explosion on 10 May 1716.

[60] Following this precedent, all Methodist chapels were committed in trust to him until by a "deed of declaration", all his interests in them were transferred to a body of preachers called the "Legal Hundred".

[65] Two years later, to help preachers work more systematically and societies receive services more regularly, Wesley appointed "helpers" to definitive circuits.

[73] When, in 1746, Wesley read Lord King's account of the primitive church, he became convinced that apostolic succession could be transmitted through not only bishops, but also presbyters (priests).

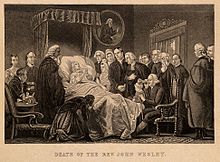

He begged Wesley to stop before he had "quite broken down the bridge" and not embitter his [Charles'] last moments on earth, nor "leave an indelible blot on our memory.

[84] In this method, Wesley believed that the living core of Christianity was contained in Scripture (the Bible), and that it was the sole foundational source of theological development.

"[86] The doctrines which Wesley emphasised in his sermons and writings are prevenient grace, present personal salvation by faith, the witness of the Spirit, and entire sanctification.

Entire sanctification, he described in 1790, as the "grand depositum which God has lodged with the people called 'Methodists'" and that the propagation of this doctrine was the reason that He brought Methodists into existence.

[88] Wesley defined it as:"That habitual disposition of soul which, in the sacred writings, is termed holiness; and which directly implies, the being cleansed from sin, 'from all filthiness both of flesh and spirit;' and, by consequence, the being endued with those virtues which were in Christ Jesus; the being so 'renewed in the image of our mind,' as to be 'perfect as our Father in heaven is perfect.

"[95] He described perfection as a second blessing and instantaneous sanctifying experience; he maintained that individuals could have the assurance of their entire sanctification through the testimony of the Holy Spirit.

When in 1739 Wesley preached a sermon on Freedom of Grace, attacking the Calvinistic understanding of predestination as blasphemous, as it represented "God as worse than the devil," Whitefield asked him not to repeat or publish the discourse, as he did not want a dispute.

[123] In the summer of 1771, Mary Bosanquet wrote to John Wesley to defend her and Sarah Crosby's work preaching and leading classes at her orphanage, Cross Hall.

[129] Although his Letter to a Roman Catholic (1749), a conciliatory appeal for understanding and shared Christian faith, is sometimes seen as an act of religious tolerance, Wesley remained deeply rooted in the anti-Catholicism characteristic of 18th-century England.

In his Christian Library (1750), he writes about mystics such as Macarius of Egypt, Ephrem the Syrian, Madame Guyon, François Fénelon, Ignatius of Loyola, John of Ávila, Francis de Sales, Blaise Pascal, and Antoinette Bourignon.

[165] Wesley's call to personal and social holiness continues to challenge Christians who attempt to discern what it means to participate in the Kingdom of God.

[168] In his early ministry years, Wesley was barred from preaching in many parish churches and the Methodists were persecuted; he later became widely respected, and by the end of his life, was described as "the best-loved man in England".