Armistice of 11 November 1918

The actual terms, which were largely written by Foch, included the cessation of hostilities on the Western Front, the withdrawal of German forces from west of the Rhine, Entente occupation of the Rhineland and bridgeheads further east, the preservation of infrastructure, the surrender of aircraft, warships, and military materiel, the release of Allied prisoners of war and interned civilians, eventual reparations, no release of German prisoners and no relaxation of the naval blockade of Germany.

[5] With the collapse of Bulgaria, and Italian victory in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, the road was open to an invasion of Germany from the south via Austria.

[7] Although morale on the German front line was reasonable, battlefield casualties, starvation rations and Spanish flu had caused a desperate shortage of manpower, and those recruits that were available were war-weary and disaffected.

[9] In addition, he recommended the acceptance of the main demands of US president Woodrow Wilson (the Fourteen Points) including putting the Imperial Government on a democratic footing, hoping for more favorable peace terms.

This enabled him to save the face of the Imperial German Army and put the responsibility for the capitulation and its consequences squarely into the hands of the democratic parties and the parliament.

"[10] On 3 October 1918, the liberal Prince Maximilian of Baden was appointed Chancellor of Germany,[11] replacing Georg von Hertling in order to negotiate an armistice.

[12] After long conversations with the Kaiser and evaluations of the political and military situations in the Reich, by 5 October 1918 the German government sent a message to Wilson to negotiate terms on the basis of a recent speech of his and the earlier declared "Fourteen Points".

"[13] As a precondition for negotiations, Wilson demanded the retreat of Germany from all occupied territories, the cessation of submarine activities and the Kaiser's abdication, writing on 23 October: "If the Government of the United States must deal with the military masters and the monarchical autocrats of Germany now, or if it is likely to have to deal with them later in regard to the international obligations of the German Empire, it must demand not peace negotiations but surrender.

On 3 November 1918, Prince Max, who had been in a coma for 36 hours after an over-dose of sleep-inducing medication taken to help with influenza and only just recovered, discovered that both Turkey and Austria-Hungary had concluded armistices with the Allies.

General von Gallwitz had described this eventuality as being "decisive" to the Chancellor in discussions some weeks before, as it would mean that Austrian territory would become a spring-board for an Allied attack on Germany from the south.

[21] The sailors' revolt that took place during the night of 29 to 30 October 1918 in the port of Wilhelmshaven spread across Germany within days and led to the proclamation of a republic on 9 November and to the announcement of the abdication of Wilhelm II.

[23] Also on 9 November, Max von Baden handed the office of chancellor to Friedrich Ebert, a Social Democrat who the same day became co-chair of the Council of the People's Deputies.

The German High Command pushed the blame for the surrender away from the Army and onto others, including the socialists who were supporting and running the government in Berlin.

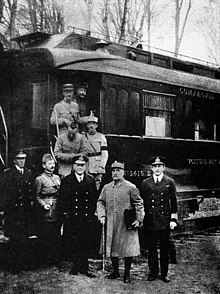

The German delegation headed by Erzberger crossed the front line in five cars and was escorted for ten hours across the devastated war zone of Northern France, arriving on the morning of 8 November 1918.

The Germans were able to correct a few impossible demands (for example, the decommissioning of more submarines than their fleet possessed), extend the schedule for the withdrawal and register their formal protest at the harshness of Allied terms.

The cabinet had earlier received a message from Paul von Hindenburg, head of the German High Command, requesting that the armistice be signed even if the Allied conditions could not be improved on.

Eastern and African Fronts C. At sea D. General The British public was notified of the armistice by a subjoined official communiqué issued from the Press Bureau at 10:20 a.m., when British Prime Minister David Lloyd George announced: "The armistice was signed at five o'clock this morning, and hostilities are to cease on all fronts at 11 a.m.

"[41] An official communique was published by the United States at 2:30 pm: "In accordance with the terms of the Armistice, hostilities on the fronts of the American armies were suspended at eleven o'clock this morning.

One hour later, Foch, accompanied by a British admiral, presented himself at the Ministry of War, where he was immediately received by Georges Clemenceau, the Prime Minister of France.

At the first shot fired from the Eiffel Tower, the Ministry of War and the Élysée Palace displayed flags, while bells around Paris rang.

[45] According to Thomas R. Gowenlock, an intelligence officer with the U.S. First Division, shelling from both sides continued during the rest of the day, ending only at nightfall.

[48] Augustin Trébuchon was the last Frenchman to die when he was shot on his way to tell fellow soldiers, who were attempting an assault across the Meuse river, that hot soup would be served after the ceasefire.

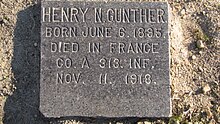

[citation needed] The final Canadian, and Commonwealth, soldier to die, Private George Lawrence Price, was shot and killed by a sniper while part of a force advancing into the Belgian town of Ville-sur-Haine just two minutes before the armistice to the north of Mons at 10:58 a.m.[citation needed] Henry Gunther, an American, is generally recognized as the last soldier killed in action in World War I.

In the United States, Congress opened an investigation to find out why and if blame should be placed on the leaders of the American Expeditionary Forces, including John Pershing.

Additionally, with the fall of Austria-Hungary, an offensive was being prepared across the Alps towards Munich, Poland was in turmoil, and an air-offensive was being planned by the Independent Air Force under Trenchard against Berlin.

[6] Yet at the time of the armistice, the Western Front was still some 720 kilometres (450 mi) from Berlin, and the Kaiser's armies had retreated from the battlefield in good order.

"[58] In a hearing before the Committee on Inquiry of the National Assembly on November 18, 1919, a year after the war's end, Hindenburg declared, "As an English general has very truly said, the German Army was 'stabbed in the back'.