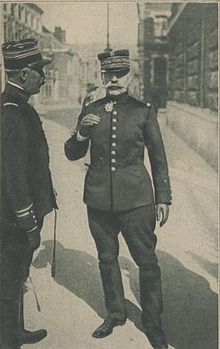

Ferdinand Foch

Ordered west to defend Paris, Foch's prestige soared as a result of the victory at the Marne, for which he was widely credited as a chief protagonist while commanding the French Ninth Army.

He played a decisive role in halting a renewed German advance on Paris in the Second Battle of the Marne, after which he was promoted to Marshal of France.

Author Larry H. Addington says, "to a large extent the final Allied strategy which won the war on land in Western Europe in 1918 was Foch's alone.

Ferdinand Foch was born in Tarbes, a municipality in the department of Hautes-Pyrénées, in southwestern France, into a modest, devout, middle-class Catholic family.

[8][9][10] His last name reflects the ancestry of his father, a civil servant from Valentine, a village in Haute-Garonne, whose lineage may trace back to 16th-century Alsace.

Foch acquitted himself well, covering the withdrawal to Nancy and the Charmes Gap before launching a counter-attack that prevented the Germans from crossing the River Meurthe.

[31] Only a week after taking command, with the whole French Army in full retreat, he was forced to fight a series of defensive actions to prevent a German breakthrough.

[34] As assistant Commander-in-Chief with responsibility for co-ordinating the activities of the northern French armies and liaising with the British forces; this was a key appointment as the Race to the Sea was then in progress.

Field Marshal Sir John French, C-in-C of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had described Foch in August 1914 to J. E. B. Seely, a liaison officer, as "the sort of man with whom I know I can get on" and later in February 1915 described him to Lord Selbourne as "the best general in the world".

By contrast, Lieutenant General William Robertson, another British officer, thought that Foch was "rather a flat-catcher,[35] a mere professor, and very talkative" (28 September 1915).

[37] In 1915, his responsibilities by now crystallised in command of the Northern Army Group, he conducted the Artois Offensive and, in 1916, the French effort at the Battle of the Somme.

Like Pétain, Foch favoured only limited attacks (he had told Lieutenant General Sir Henry Wilson, another British Army officer, that the planned Flanders offensive was "futile, fantastic & dangerous") until the Americans, who had joined the war in April 1917, were able to send large numbers of troops to France.

[39] The Anglo-French leadership agreed in early September to send 100 heavy guns to Italy, 50 of them from the French army on the left of Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, C-in-C of the BEF, rather than the 300 which Lloyd George wanted.

The French tried to have Foch as representative to increase their control over the Western Front (by contrast, Cadorna was disgraced after the recent Battle of Caporetto) and Wilson, a personal friend of Foch, was deliberately appointed as a rival to General Sir William Robertson, the British Chief of the Imperial General Staff, an ally of Haig's, who had lost 250,000 men at the battle of Ypres the same year.

At a Supreme War Council meeting in London (14–15 March), with a German offensive clearly imminent, Foch protested to no avail for the formation of the Allied Reserve.

[45][46] On the evening of 24 March, after the German spring offensive was threatening to split apart the British and French forces, Foch telegraphed Wilson (who by now had replaced Robertson as Chief of the Imperial General Staff) "asking what [he] thought of situation & we are of one mind that someone must catch a hold or we shall be beaten".

"[22] At the sixth session of the Supreme War Council on 1 June Foch complained that the BEF was still shrinking in size and infuriated Lloyd George by implying that the British government was withholding manpower.

Along with the British commander, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, Foch planned the Grand Offensive, opening on 26 September 1918, which led to the defeat of Germany.

However, he refused to accede to the German negotiators' immediate request to declare a ceasefire or truce so that there would be no more useless waste of lives among the common soldiers.

However, historians took a less favourable view of Foch's talents as commander, particularly as the idea took root that his military doctrines had set the stage for the futile and costly offensives of 1914 in which French armies suffered devastating losses.

Supporters and critics continue to debate Foch's strategy and instincts as a commander, as well as his exact contributions to the Marne "miracle": Foch's counter-attacks at the Marne generally failed, but his sector resisted determined German attacks while holding the pivot on which the neighbouring French and British forces depended in rolling back the German line.

Foch's pre-war contributions as a military theorist and lecturer have also been recognised, and he has been credited as "the most original and subtle mind in the French Army" of the early 20th century.

[27] In January 1919, at the Paris Peace Conference Foch presented a memorandum to the Allied plenipotentiaries in which he stated: Henceforward the Rhine ought to be the Western military frontier of the German countries.

Henceforward Germany ought to be deprived of all entrance and assembling ground, that is, of all territorial sovereignty on the left bank of the river, that is, of all facilities for invading quickly, as in 1914, Belgium, Luxembourg, for reaching the coast of the North Sea and threatening the United Kingdom, for outflanking the natural defences of France, the Rhine, Meuse, conquering the Northern Provinces and entering the Parisian area.

Foch considered the Treaty of Versailles to be "a capitulation, a treason" because he believed that only permanent occupation of the Rhineland would grant France sufficient security against a revival of German aggression.

The local veteran chosen to present flags to the commanders was a Kansas City haberdasher, Harry S. Truman, who would later serve as 33rd President of the United States from 1945 to 1953.

Foch made a 3000-mile circuit through the American Midwest and industrial cities such as Pittsburgh and then on to Washington, D.C., which included ceremonies at Arlington National Cemetery for what was then called Armistice Day.

His career began as the Lebel Model 1886 rifle had just entered service, and ended after Foch had commanded hundreds of thousands of soldiers in World War I.

Nevertheless, one of the major avenues of the City of Bydgoszcz, located then in the Polish corridor, holds Foch's name as sign of gratitude for his campaigning for an independent Poland.

The position of Marshal Foch Professor of French Literature at the University of Oxford was founded in 1918 shortly after the end of the First World War.