Armory Show

"The origins of the show lie in the emergence of progressive groups and independent exhibitions in the early 20th century (with significant French precedents), which challenged the aesthetic ideals, exclusionary policies, and authority of the National Academy of Design, while expanding exhibition and sales opportunities, enhancing public knowledge, and enlarging audiences for contemporary art.

[5] In January 1912, Walt Kuhn, Walter Pach, and Arthur B. Davies joined with some two dozen of their colleagues to reinforce a professional coalition: AAPS.

[6] Other founding AAPS members included D. Putnam Brinley, Gutzon Borglum, John Frederick Mowbray-Clarke, Leon Dabo, William J. Glackens, Ernest Lawson, Jonas Lie, George Luks, Karl Anderson, James E.Fraser, Allen Tucker, and J. Alden Weir.

[6] AAPS was to be dedicated to creating new exhibition opportunities for young artists outside of the existing academic boundaries, as well as to providing educational art experiences for the American public.

[citation needed] The AAPS members spent more than a year planning their first project: the International Exhibition of Modern Art, a show of giant proportions, unlike any New York had seen.

[citation needed] Once the space had been secured, the most complicated planning task was selecting the art for the show, particularly after the decision was made to include a large proportion of vanguard European work, most of which had never been seen by an American audience.

[8] While in Paris Kuhn met up with Pach, who knew the art scene there intimately, and was friends with Marcel Duchamp and Henri Matisse; Davies joined them there in November 1912.

Quinn opened the Armory Show exhibition with the words:... it was time the American people had an opportunity to see and judge for themselves concerning the work of the Europeans who are creating a new art.

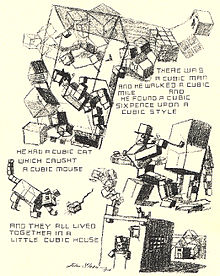

[12] News reports and reviews were filled with accusations of quackery, insanity, immorality, and anarchy, as well as parodies, caricatures, doggerels, and mock exhibitions.

Julian Street, an art critic, wrote that the work resembled "an explosion in a shingle factory" (this quote is also attributed to Joel Spingarn[15]), and cartoonists satirized the piece.

[citation needed] Duchamp's brother, who went by the "nom de guerre" Jacques Villon, also exhibited, sold all his Cubist drypoint etchings, and struck a sympathetic chord with New York collectors who supported him in the following decades.

A visit of an investigator to the show and his report on the pictures caused Lieutenant Governor Barratt O'Hara to order an immediate examination of the entire exhibition.

[20] In 1944 the Cincinnati Art Museum mounted a smaller version, in 1958 Amherst College held an exhibition of 62 works, 41 of which were in the original show, and in 1963 the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in Utica, New York, organized the "1913 Armory Show 50th Anniversary Exhibition" sponsored by the Henry Street Settlement in New York, which included more than 300 works.

[citation needed] Starting with a small exhibition in 1994, by 2001 The Armory Show, now held at the Javits Center, evolved into a "hugely entertaining" (The New York Times) annual contemporary arts festival with a strong commercial bent.

[12] In addition, the Greenwich Historical Society presented The New Spirit and the Cos Cob Art Colony: Before and After the Armory Show, from October 9, 2013, through January 12, 2014.

Essentially independent, necessarily complete, it need not immediately satisfy the mind: on the contrary, it should lead it, little by little, towards the fictitious depths in which the coordinative light resides.

[33] "Mare's ensembles were accepted as frames for Cubist works because they allowed paintings and sculptures their independence", writes Christopher Green, "creating a play of contrasts, hence the involvement not only of Gleizes and Metzinger themselves, but of Marie Laurencin, the Duchamp brothers (Raymond Duchamp-Villon designed the facade) and Mare's old friends Léger and Roger La Fresnaye".

[34] La Maison Cubiste was a fully furnished house, with a staircase, wrought iron banisters, a living room—the Salon Bourgeois, where paintings by Marcel Duchamp, Metzinger (Woman with a Fan), Gleizes, Laurencin and Léger were hung—and a bedroom.