Arrow

A typical arrow usually consists of a long, stiff, straight shaft with a weighty (and usually sharp and pointed) arrowhead attached to the front end, multiple fin-like stabilizers called fletchings mounted near the rear, and a slot at the rear end called a nock for engaging the bowstring.

A container or bag carrying additional arrows for convenient reloading is called a quiver.

[2] The oldest evidence of likely arrowheads, dating to c. 64,000 years ago, were found in Sibudu Cave, current South Africa.

[3][4][5][6][7] Likely arrowheads made from animal bones have been discovered in the Fa Hien Cave in Sri Lanka which are also the oldest evidence for the use of arrows outside of Africa dating to c. 48,000 years ago.

Arrows recovered from the Mary Rose, an English warship that sank in 1545 whose remains were raised in 1982, were mostly 76 cm (30 in) long.

[12] Very short arrows have been used, shot through a guide attached either to the bow (an "overdraw") or to the archer's wrist (the Turkish "siper").

[13] These may fly farther than heavier arrows, and an enemy without suitable equipment may find himself unable to return them.

Bows with higher draw weight will generally require stiffer arrows, with more spine (less flexibility) to give the correct amount of flex when shot.

By reinforcing the area most likely to break, the arrow is more likely to survive impact, while maintaining overall flexibility and lighter weight.

Barreled arrow shafts are considered the zenith of pre-industrial archery technology, reaching their peak design among the Ottomans.

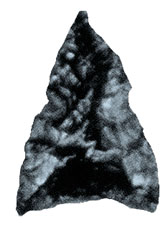

[17][18] The arrowhead or projectile point is the primary functional part of the arrow, and plays the largest role in determining its purpose.

Some arrows may simply use a sharpened tip of the solid shaft, but it is far more common for separate arrowheads to be made, usually from metal, horn, or some other hard material.

[11] Points attached with caps are simply slid snugly over the end of the shaft, or may be held on with hot glue.

Split-shaft construction involves splitting the arrow shaft lengthwise, inserting the arrowhead, and securing it using a ferrule, sinew, or wire.

They are designed to keep the arrow pointed in the direction of travel by strongly damping down any tendency to pitch or yaw.

[25] Also, arrows without fletching (called bare shaft) are used for training purposes, because they make certain errors by the archer more visible.

The burning-wire method is popular because different shapes are possible by bending the wire, and the fletching can be symmetrically trimmed after gluing by rotating the arrow on a fixture.

In traditional archery, some archers prefer a left rotation because it gets the hard (and sharp) quill of the feather farther away from the arrow-shelf and the shooter's hand.

The extra fletching generates more drag and slows the arrow down rapidly after a short distance of about 30 m (98 ft) or so.

Brightly colored wraps can also make arrows much easier to find in the brush, and to see in downrange targets.

The nock's slot should be rotated at an angle chosen so that when the arrow bends, it avoids or slides on the bowstave.

The sturdiest nocks are separate pieces made from wood, plastic, or horn that are then attached to the end of the arrow.

[33] A practical disadvantage compared to a nock would be preserving the optimal rotation of the arrow, so that when it flexes, it does not hit the bowstave.

Softer woods like pine or cedar also required some sort of reinforcement of hardwood, bone or horn which kept the string from splitting their shaft upon release.

Arrows sometimes need to be repaired, so it's important that the paints be compatible with glues used to attach arrowheads, fletchings, and nocks.