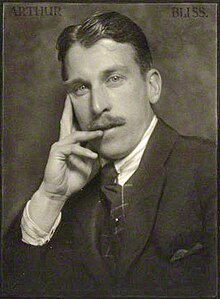

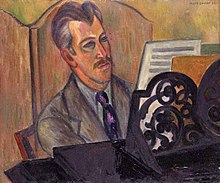

Arthur Bliss

In the post-war years he quickly became known as an unconventional and modernist composer, but within the decade he began to display a more traditional and romantic side in his music.

In Bliss's later years, his work was respected but was thought old-fashioned, and it was eclipsed by the music of younger colleagues such as William Walton and Benjamin Britten.

[2] Bliss was educated at Bilton Grange preparatory school, Rugby and Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he studied classics, but also took lessons in music from Charles Wood.

The music scholar Byron Adams writes, "Despite the apparent heartiness and equilibrium of the composer's public persona, the emotional wounds inflicted by the war were deep and lasting.

[1] Although he had begun composing while still a schoolboy, Bliss later suppressed all his juvenilia, and, with the single exception of his 1916 Pastoral for clarinet and piano, reckoned the 1918 work Madam Noy as his first official composition.

[5] The work was well received; in The Manchester Guardian, Samuel Langford called Bliss "far and away the cleverest writer among the English composers of our time";[9] The Times praised it highly (though doubting whether much was gained by the designation of the four movements as purple, red, blue and green) and commented that the symphony confirmed Bliss's transition from youthful experimenter to serious composer.

[10] After the third performance of the work, at the Queen's Hall under Sir Henry Wood, The Times wrote, "Continually changing patterns scintillate … till one is hypnotised by the ingenuity of the thing.

[1] From the mid-1920s onwards Bliss moved more into the established English musical tradition, leaving behind the influence of Stravinsky and the French modernists, and in the words of the critic Frank Howes, "after early enthusiastic flirtations with aggressive modernism admitted to a romantic heart and [has] given rein to its less and less inhibited promptings"[13] He wrote two major works with American orchestras in mind, the Introduction and Allegro (1926), dedicated to the Philadelphia Orchestra and Leopold Stokowski, and Hymn to Apollo (1926) for the Boston Symphony and Pierre Monteux.

"[14] During the decade Bliss wrote chamber works for leading soloists including a Clarinet Quintet for Frederick Thurston (1932) and a Viola Sonata for Lionel Tertis (1933).

He felt impelled to return to England to do what he could for the war effort, and in 1941, leaving his wife and children in California, he made the hazardous Atlantic crossing.

[30] Priestley attributed this to the failure of the conductor, Karl Rankl, to learn the music or to cooperate with Brook, and to lack of rehearsal of the last act.

[26] The critics attributed it to Priestley's inexperience as an opera librettist, and to the occasional lack of "the soaring tune for the human voice" in Bliss's music.

[13] Bliss, who composed quickly and with facility, was able to discharge the many duties of the post, providing music as required for state occasions, from the birth of a child to the Queen, to the funeral of Winston Churchill, to the investiture of the Prince of Wales.

The party included the violinist Alfredo Campoli, the oboist Léon Goossens, the soprano Jennifer Vyvyan, the conductor Clarence Raybould and the pianist Gerald Moore.

[36] Bliss returned to Moscow in 1958, as a member of the jury of the International Tchaikovsky Competition, with fellow jurors including Emil Gilels and Sviatoslav Richter.

His works from that decade include his Second String Quartet (1950); a scena, The Enchantress (1951), for the contralto Kathleen Ferrier; a Piano Sonata (1952); and a Violin Concerto (1955), for Campoli.

He was delegated by his colleagues Walton, Britten, Peter Maxwell Davies and Richard Rodney Bennett to make a strong protest to William Glock, the BBC's controller of music.

[n 7] Bliss continued to compose into his eighth and ninth decades, in which his works included the Cello Concerto (1970) for Mstislav Rostropovich, the Metamorphic Variations for orchestra (1972),[3] and a final cantata, Shield of Faith (1974), for soprano, baritone, chorus and organ, celebrating 500 years of St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, setting poems chosen from each of the five centuries of the chapel's existence.

[45] The musicologist Christopher Palmer was censorious of those who sought to characterise Bliss's music as "an early tendency to enfant terribilisme yielding very quickly to a compromise with the Establishment and a perpetuating of the Elgar tradition".

The second Chamber Rhapsody (1919) is "an idyllic work for soprano, tenor, flute, cor anglais, and bass, the two voices vocalising on 'Ah' throughout, and being placed as instruments in the ensemble.

"[7] Bliss contrasted the pastoral tone of that work with Rout (1920) an uproarious piece for soprano and instrumental ensemble; " the music conveys an impression such as one might gather at an open window at carnival time … the singer is given a series of meaningless syllables chosen for their phonetic effect".

"[46] Burn observes that in three works written soon after his marriage, the Oboe Quintet (1927), Pastoral (1929) and Serenade (1929), "Bliss's voice assumed the mantle of maturity … all are imbued with a quality of contentment reflecting his serenity.

Some by the performers for whom they were written, such as the concertos for piano (1938), violin (1955) and cello (1970); some by literary and theatrical partners, such as the film music, ballets, cantatas and The Olympians; some by painters, such as the Serenade and the Metamorphic Variations; some by classical literature, such as Hymn to Apollo (1926), The Enchantress, and Pastoral.

A contemporary critic, in a broadly favourable review, wrote, "Bliss has wisely cleared his idiom of modern harmonic astringency.

[48] Both Palmer and Burn comment on a sinister vein that sometimes breaks out in Bliss's music, in passages such as the Interlude "Through the valley of the shadow of Death" in The Meditations on a Theme of John Blow, and the orchestral introduction to The Beatitudes.

[17] In a centenary assessment of Bliss's music, Burn singles out for mention "the youthful vigour of A Colour Symphony", "the poignant humanity of Morning Heroes", "the romantic lyricism of the Clarinet Quintet", "the drama of Checkmate, Miracle in the Gorbals and Things to Come", and "the spiritual probing of the Meditations on a Theme of John Blow and Shield of Faith.

"[2] Other works of Bliss classed by Palmer as among the finest are the Introduction and Allegro, the Music for Strings, the Oboe Quintet, A Knot of Riddles and the Golden Cantata.

[51] On receiving the Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society in 1963, Bliss said, "I don't claim to have done more than light a small taper at the shrine of music.

[6]Girl in a Broken Mirror A documentary featuring the ballet The Lady of Shalott performed by school pupils from Leicestershire and the LSSO conducted by Eric Pinkett.