Arthur O. Austin

He bought a large estate in Barberton, Ohio, lived in the mansion, and built an extensive outdoor electrical laboratory on the grounds.

[4] During the First World War, the US Navy planned work on a military radio facility in Monroe, North Carolina, using arc converter transmitters produced by the Federal Telegraph Company, generating approximately 1 MW of power.

[5] Austin invented an electrically heated, oil filled porcelain insulator used to support radio transmission towers.

The assembly was filled with oil kept warm by a 120-watt electric heater; a thermostat kept the exterior of the insulator above the dew point, preventing moisture from condensing on its surface which would result in leakage of radio frequency (RF) energy.

After obtaining permission from the Federal Radio Commission, a new transmitter was built on a hill nine miles south of the city, leaving the studio downtown.

[13] Austin had previously worked on sectionalized high-tension power line towers and held a patent on that design.

During initial testing, the 1,000 watt WHK signal could be heard in New Zealand whereas the previous transmitter, with the same power level, was not even audible throughout all of Cleveland.

The author speculated that external floodlighting, neon tubes driven from the radiated RF energy, or wind generators might all be practical alternatives to the use of gas.

The large air gap between the primary and secondary windings results in a low coupling capacitance and high breakdown voltage.

[22] The 1971 Austin Insulator product catalog listed 21 standard types with power ratings from 0.7 to 7.0 kVA weighing 70–340 pounds (32–154 kg), with the larger units only available on special order.

It seems that Arthur Austin was happily making ring transformers when he was approached by Hughey and Phillips, a company based somewhere around Los Angeles that was into several types of lighting.

[3] He attended high school in Stockton[1] then went to Leland Stanford University, graduating in 1903 with a Bachelors of Arts degree in electrical engineering.

[25] Two years later, Austin married Eleanor's sister Augusta in Los Gatos, California; the couple had two daughters, Barbara and Martha.

[3] Austin had a brother, Edward, who worked on building Ohio Brass's manufacturing facility in Niagara Falls, Ontario.

[28] The house, which had gold-leaf ceilings,[29] was described in 2005 by the Akron Beacon Journal as having 52 rooms, "a breathtaking vista from its east-side perch", and being "the most opulent residence between New York City and Chicago".

There was an effort on the part of the Barberton community to preserve the property for its historic value, but funding could not be secured and the house was torn down.

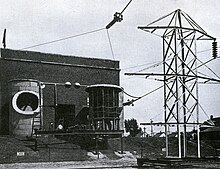

The high voltages necessitated physically large equipment and clearances, which meant the labs could no longer fit inside buildings and had to be built outdoors.

[33] A capacitor and synchronous switch was used to produce a transient overvoltage and a spark across a sphere gap which could be applied to objects being studied.

[11] A 1933 newspaper report wrote about the lab:[34] The courtyard of the laboratory, where most of the experiments have been conducted, is a weird place, filled with cage-like structural towers, and dominated by three mammoth transformers.

From an insulated ball suspended in the air, at Austin's will 30-foot flashes of lightning leap to the ground with a crack like a rifle shot.The space available on the Barber estate was outgrown by 1933 and in 1934, the third lab was built by Ohio Brass adjacent to their factory.

Additional tests on the plane's LeBlond 60 engine showed that it would continue to run at idle speed after being struck.

Lightning strikes on the tip of the rudder resulted in small holes burned through the fabric covering where it contacted the duralumin frame.

[38] As of 1930, when these findings were published by Popular Mechanics, additional experiments were planned to investigate the effect of lightning on fuel tanks, the engine crankcase, flight instruments, and control cables.