Asceticism

[6] However, ascetics maintain that self-imposed constraints bring them greater freedom in various areas of their lives, such as increased clarity of thought and the ability to resist potentially destructive temptations.

[13][14] In the Baháʼí Faith, according to Shoghi Effendi, the maintenance of a high standard of moral conduct is neither to be associated or confused with any form of extreme asceticism, nor of excessive and bigoted puritanism.

[15]: 44 Notable Christian authors of Late Antiquity such as Origen, St Jerome, John Chrysostom, and Augustine of Hippo, interpreted meanings of the Biblical texts within a highly asceticized religious environment.

[16] The Dead Sea Scrolls revealed ascetic practices of the ancient Jewish sect of Essenes who took vows of abstinence to prepare for a holy war.

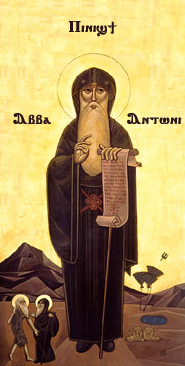

Other Christian practitioners of asceticism include saints such as Paul the Hermit, Simeon Stylites, David of Wales, John of Damascus, Peter Waldo, Tamar of Georgia,[17] and Francis of Assisi.

[23] Evidence of extreme asceticism in Christianity appear in second century texts and thereafter, in both Eastern & Western Christian traditions, such as the practice of chaining the body to rocks, eating only grass,[24] praying seated on a pillar in the elements for decades such as by the monk Simeon Stylites,[25] solitary confinement inside a cell, abandoning personal hygiene and adopting lifestyle of a beast, self-inflicted pain and voluntary suffering,[22][26] however they were often rejected as beyond measure by other ascetics such as Barsanuphius of Gaza and John the Prophet.

The Gnostikos is the second volume of a trilogy containing the Praktikos, intended for young monks to achieve apatheia, i.e., "a state of calm which is the prerequisite for love and knowledge",[31] in order to purify their intellect and make it impassible, to reveal the truth hidden in every being.

The ascetic literature of early Christianity was influenced by pre-Christian Greek philosophical traditions, especially Plato and Aristotle, looking for the perfect spiritual way of life.

[40][41][43] Scholars in the field of Islamic studies have argued that asceticism (zuhd) served as a precursor to the later doctrinal formations of Sufis that began to emerge in the tenth century[37] through the works of individuals such as al-Junayd, al-Qushayrī, al-Sarrāj, al-Hujwīrī and others.

[44][45] Sufism emerged and grew as a mystical,[37] somewhat hidden tradition in the mainstream Sunni and Shia denominations of Islam,[37] state Eric Hanson and Karen Armstrong, likely in reaction to "the growing worldliness of Umayyad and Abbasid societies".

[46] Acceptance of asceticism emerged in Sufism slowly because it was contrary to the sunnah, states Nile Green, and early Sufis condemned "ascetic practices as unnecessary public displays of what amounted to false piety".

[48][49] Sufis were highly influential and greatly successful in spreading Islam between the 10th and 19th centuries,[37] particularly to the furthest outposts of the Muslim world in the Middle East and North Africa, the Balkans and Caucasus, the Indian subcontinent, and finally Central, Eastern, and Southeast Asia.

[50][51] Sufism was adopted and then grew particularly in the frontier areas of Islamic states,[37][50] where the asceticism of its fakirs and dervishes appealed to populations already used to the monastic traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism, and medieval Christianity.

[58] The history of Jewish asceticism is traceable to first millennium BCE era with the references of the Nazirite (or Nazorean, Nazarene, Naziruta, Nazir), whose rules of practice are found in Book of Numbers 6:1–21.

[59] The ascetic practices included not cutting the hair, abstaining from eating meat or grapes, abstention from wine, or fasting and hermit style living conditions for a period of time.

[59][60] After the Jews returned from the Babylonian exile and the Mosaic institution was done away with, a different form of asceticism arose when Antiochus IV Epiphanes threatened the Jewish religion in 167 BCE.

[63] The Ashkenazi Hasidim (Hebrew: חסידי אשכנז, romanized: Chassidei Ashkenaz) were a Jewish mystical, ascetic movement in the German Rhineland whose practices are documented in the texts of the 12th and 13th centuries.

[72] However, Indian mythologies also describe numerous ascetic gods or demons who pursued harsh austerities for decades or centuries that helped each gain special powers.

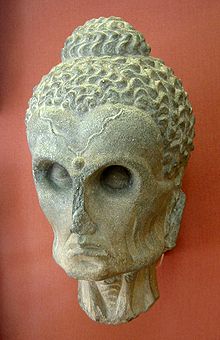

[79] In the Theravada tradition of Thailand, medieval texts report of ascetic monks who wander and dwell in the forest or crematory alone, do austere practices, and these came to be known as Thudong.

[86] More ancient Chinese Buddhist asceticism, somewhat similar to Sokushinbutsu are also known, such as the public self-immolation (self-cremation, as shaoshen 燒身 or zifen 自焚)[87] practice, aimed at abandoning the impermanent body.

His hair and beard grow longer, he spends long periods of time in absorption, musing and meditating and therefore he is called "sage" (muni).

[113] Other behavioral characteristics of the Sannyasi include: ahimsa (non-violence), akrodha (not become angry even if you are abused by others),[114] disarmament (no weapons), chastity, bachelorhood (no marriage), avyati (non-desirous), amati (poverty), self-restraint, truthfulness, sarvabhutahita (kindness to all creatures), asteya (non-stealing), aparigraha (non-acceptance of gifts, non-possessiveness) and shaucha (purity of body speech and mind).

[115][116] In the Bhagavad Gita, verse 17.5 criticize a form of asceticism that diverges from scriptural guidance and is driven by pride, ego, or attachment, rather than for genuine spiritual growth.

[118][119][120] In Jainism, the ultimate goal of life is to achieve the liberation of soul from endless cycle of rebirths (moksha from samsara), which requires ethical living and asceticism.

[124] Inner austerities include expiation, confession, respecting and assisting mendicants, studying, meditation and ignoring bodily wants in order to abandon the body.

For more than twelve years the Venerable Ascetic Mahivira neglected his body and abandoned the care of it; he with equanimity bore, underwent, and suffered all pleasant or unpleasant occurrences arising from divine powers, men, or animals.Both Mahavira and his ancient Jaina followers are described in Jainism texts as practicing body mortification and being abused by animals as well as people, but never retaliating and never initiating harm or injury (ahimsa) to any other being.

[127] The practice of body mortification is called kaya klesha in Jainism and is found in verse 9.19 of the Tattvartha Sutra by Umaswati, the most authoritative oldest surviving Jaina philosophical text.

[130][131] However, during the four months of monsoon (rainy season) known as chaturmaas, they stay at a single place to avoid killing life forms that thrive during the rains.

Male Digambara sect monks do not wear any clothes, carry nothing with them except a soft broom made of shed peacock feathers (pinchi) to gently remove any insect or living creature in their way or bowl, and they eat with their hands.

[136] While Sikhism treats lust as a vice, it has at the same time unmistakingly pointed out that man must share the moral responsibility by leading the life of a householder.