Asian immigration to the United States

Asian Americans experienced exclusion, and limitations to immigration, by the United States law between 1875 and 1965, and were largely prohibited from naturalization until the 1940s.

[1] The first Asian-origin people known to arrive in North America after the beginning of the European colonization were a group of Filipinos known as "Luzonians" or Luzon Indians.

[5] With the establishment of the Old China Trade in the late 18th century, a handful of Chinese merchants were recorded as residing in the United States by 1815.

Originating primarily from China, Japan, Korea, and the Philippines, these early migrants were predominantly contract workers who labored on plantations.

[10] Taking refuge from Japanese imperialism and growing poverty and famine in Korea, and encouraged by Christian missionaries, thousands of Koreans migrated to Hawaii in the early 1900s.

[12] The first major wave of Asian immigration to the continental United States occurred primarily on the West Coast during the California Gold Rush, starting in the 1850s.

[13] Most Chinese immigrants in California, which they called Gam Saan ("Gold Mountain"), were also from the Guangdong province; they sought sanctuary from conflicts such as the Opium Wars and ensuing economic instability, and hoped to earn wealth to send back to their families.

[14] As in Hawaii, many capitalists in California and elsewhere (including as far as North Adams, Massachusetts[15]) sought Asian immigrants to fill an increasing demand for labor in gold mines, factories, and on the Transcontinental Railroad.

[18] Japanese, Korean, and South Asian immigrants also arrived in the continental United States starting from the late 1800s and onwards to fill demands for labor.

Filipino migration to North America continued in this period with reports of "Manila men" in early gold camps in Mariposa County, California in the late 1840s.

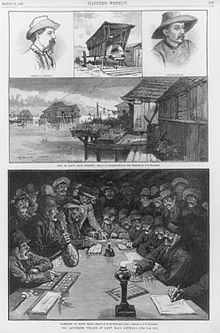

[22] In the 1860s and 1870s, nativist hostility to the presence of Asian laborers in the continental United States grew and intensified, with the formation of organizations such as the Asiatic Exclusion League.

East Asian immigrants, particularly Chinese Americans who composed the majority of the population on the mainland, were seen as the "yellow peril" and suffered violence and discrimination.

This law recognized forced laborers from Asia as well as Asian women who would potentially engage in prostitution as "undesirable" people, who would henceforth be barred from entering the United States.

In practice, the law was enforced to institute a near-complete exclusion of Chinese women from the United States, preventing male laborers from bringing their families with or after them.

[28] South Asian migrants also arrived on the East Coast, although to a lesser extent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, predominantly Bengali Muslims who worked as craftsmen and merchants, selling 'exotic' goods such as embroidered silks and rugs.

[22] Anti-Asian hostility against these both older and newer Asian immigrant groups continued, becoming explosive in events such as the Pacific Coast race riots of 1907 in San Francisco, California; Bellingham, Washington; and Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

The San Francisco riot was led by anti-Japanese activist, rebelling with violence in order to receive segregated schools for Caucasian and Japanese students.

Many Filipinos came as agricultural laborers to fill demands once answered by Chinese and Japanese immigration, with migration patterns to Hawaii extending to the mainland starting from the 1920s.

After exclusion, existing Chinese immigrants were further excluded from agricultural labor by racial hostility, and as jobs in railroad construction declined, they increasingly moved into self-employment as laundry workers, store and restaurant owners, traders, merchants, and wage laborers; and they congregated in Chinatowns established in California and across the country.

A few months later in 1923, the Court ruled in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind that while Indians were considered Caucasian by contemporary racial anthropology, they were not seen as "white" in the common understanding, and were therefore ineligible for naturalization.

While roughly a third of those interned were issei (first-generation immigrants) who were ineligible for citizenship, the vast majority were nisei or sansei (second- and third-generation) who were citizens by birth.

The McCarran–Walter Act also introduced some labor qualifications for the first time, and allowed the government to bar the entry of or deport immigrants suspected of engaging in "subversive activities", such as membership in a Communist Party.

Senator Hiram Fong (R-HI) answered questions concerning the possible change in our cultural pattern by an influx of Asians: "Asians represent six-tenths of 1 percent of the population of the United States ... with respect to Japan, we estimate that there will be a total for the first 5 years of some 5,391 ... the people from that part of the world will never reach 1 percent of the population .. .Our cultural pattern will never be changed as far as America is concerned."

During the late 1960s and early and mid-1970s, Chinese immigration into the United States came almost exclusively from Taiwan creating the Taiwanese American subgroup.

He began investing in abandoned properties in Monterey Park in order to gain the interest of wealthy Chinese in Taiwan.

Due to political unrest in Asia, there was a lot of interest in overseas investment for Monterey Park from wealthy Chinese in Taiwan.

At its peak in 1970, there were nearly 600,000 Japanese Americans, making it the largest sub-group, but historically the greatest period of immigration was generations past.