Assyrian sculpture

Many works left in situ, or in museums local to their findspots,[3] have been deliberately destroyed in the recent occupation of the area by ISIS, the pace of destruction reportedly increasing in late 2016, with the Mosul offensive.

[7] A group of sixteen bronze weights shaped as lions with bilingual inscriptions in both cuneiform and Phoenician characters, were discovered at Nimrud.

[8] The Nimrud ivories, an important group of small plaques which decorated furniture, were found in a palace storeroom near reliefs, but they came from around the Mediterranean, with relatively few made locally in an Assyrian style.

The style apparently began after about 879 BC, when Ashurnasirpal II moved the capital to Nimrud, near modern Mosul in northern Iraq.

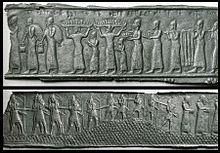

[12] Compositions are arranged on slabs, or orthostats, typically about 7 feet high, using between one and three horizontal registers of images, with scenes generally reading from left to right.

A full and characteristic set shows the campaign leading up to the siege of Lachish in 701; it is the "finest" from the reign of Sennacherib, from his palace at Nineveh and now in the British Museum.

[18] There are many reliefs of minor supernatural beings, called by such terms as "winged genie", but the major Assyrian deities are only represented by symbols.

The "genies" often perform a gesture of purification, fertilization or blessing with a bucket and cone; the meaning of this remains unclear.,[19] Especially on larger figures, details and patterns on areas such as costumes, hair and beards, tree trunks and leaves, and the like, are very meticulously carved.

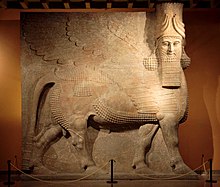

Lamassu have wings, a male human head with the elaborate headgear of a divinity, and the elaborately-braided hair and beards shared with royalty.

In the palace of Sargon II at Khorsabad, a group of at least seven lamassu and two such heroes with lions surrounded the entrance to the "throne room", "a concentration of figures which produced an overwhelming impression of power".

[28] Other accompanying figures for colossal lamassu are winged genies with the bucket and cone, thought to be the equipment for a protective or purifying ritual.

The rock is very soft and slightly soluble in water, and exposed faces degraded, and needed to be cut into before usable stone was reached.

This may have happened at the palace site, which is certainly where the carving of orthostats was done, after the slabs had been fixed into place as a facing to a mud-brick wall, using lead dowels and clamps, with the bottoms resting on a bed of bitumen.

Probably the master drew or incised the design on the slab before a team of carvers laboriously cut away the background areas and finished carving the figures.

[37] After the palaces were abandoned and lost their wooden roofs, the unbaked mud-brick walls gradually collapsed, covering the space in front of the reliefs, and largely protecting them from further damage from the weather.

The subjects were similar to the wall reliefs, but on a smaller scale; a typical band is 27 centimetres high, 1.8 metres wide, and only a millimetre thick.

[41] The Black Obelisk is of special interest as the lengthy inscriptions, with names of places and rulers that could be related to other sources, were of importance in the decipherment of cuneiform script.

[42] The Obelisk contains the earliest writing mentioning both the Persian and Jewish peoples, and confirmed some of the events described in the Bible, which in the 19th century was regarded as timely support for texts whose historical accuracy was under increasing attack.

The Assyrians probably took the form from the Hittites; the sites chosen for their 49 recorded reliefs often also make little sense if "signalling" to the general population was the intent, being high and remote, but often near water.

[51] Probably built by Sennacherib's son Esarhaddon, Shikaft-e Gulgul is a late example in modern Iran, apparently related to a military campaign.

[53] The Assyrian examples were perhaps significant in suggesting the style of the much more ambitious Persian tradition, beginning with the Behistun relief and inscription, made around 500 BC for Darius the Great, on a far grander scale, reflecting and proclaiming the power of the Achaemenid empire.

[61] Press reports of Botta's finds, from May 1843, interested the French government, who sent him funds and the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres sent him Eugène Flandin (1809–1889), an artist who had already made careful archaeological drawings of Persian antiquities in a long trip beginning in 1839.

Layard had recruited the 20-year old Hormuzd Rassam in Mosul, where his brother was British Vice-consul, to handle the pay and supervision of the diggers, and encouraged the development of his career as a diplomat and archaeologist.

[64] By October 1849 Layard was back in Mosul, accompanied by the artist Frederick Cooper, and continued to dig until April 1851, after which Rassam took charge of the excavations.

[65] By this stage, thanks to Rawlinson and other linguists working on the tablets and inscriptions brought back and other material, the Assyrian cuneiform was at the least becoming partly understood,[66] a task that progressed well over the next decade.

Initially Rassam's finds dwindled, in terms of large objects, and the British even agreed to cede the rights to half the Kuyunjik mound to the French, whose new consul, Victor Place, had resumed digging at Khorsabad.

Work has continued up to the present day, but no new palaces have been found at the capitals, and finds have mostly been isolated pieces, such as Rassam's discovery in 1878 of two of the Balawat Gates.

Many of the pieces reburied have been re-excavated, some very quickly by art dealers, and others by the Iraqi government in the 1960s, leaving them on display in situ for visitors, after the sites were configured as museums.

At the peak of excavations, the volume found was too large for the British and French to manage, and many pieces either were diverted at some point on their journey to Europe, or were given away by the museums.

As a result, there are significant groups of large lamassu corner figures and palace relief panels in Paris, Berlin, New York, and Chicago.