Nineveh

The English placename Nineveh comes from the Latin Nīnevē and the Koine Greek Nineuḗ (Νινευή) under influence of the Biblical Hebrew Nīnəweh (נִינְוֶה),[6] from the Akkadian Ninua (var.

[10] These toponyms refer to the areas to the North and South of the Khosr stream, respectively: Kuyunjiq is the name for the whole northern sector enclosed by the city walls and is dominated by the large (35 ha) mound of Tell Kuyunjiq, while Nabī (or more commonly Nebi) Yunus is the southern sector around of the mosque of Prophet Yunus/Jonah, which is located on Tell Nebi Yunus.

South of the street Al-'Asady (made by Daesh destroying swaths of the city walls) the area is called Jounub Ninawah or Shara Pepsi.

Nineveh was an important junction for commercial routes crossing the Tigris on the great roadway between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean, thus uniting the East and the West, it received wealth from many sources, so that it became one of the greatest of all the region's ancient cities,[13] and the last capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

[16][17] The context of the etymology surrounding the name is the Exorcist called a Mashmash in Sumerian, was a freelance magician who operated independent of the official priesthood, and was in part a medical professional via the act of expelling demons.

The historic Nineveh is mentioned in the Old Assyrian Empire during the reign of Shamshi-Adad I (1809–1775) in about 1800 BC as a centre of worship of Ishtar, whose cult was responsible for the city's early importance.

Successive monarchs such as Tiglath-pileser III, Sargon II, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal maintained and founded new palaces, as well as temples to Sîn, Ashur, Nergal, Shamash, Ninurta, Ishtar, Tammuz, Nisroch and Nabu.

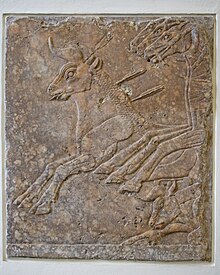

Some of the principal doorways were flanked by colossal stone lamassu door figures weighing up to 30,000 kilograms (30 t); these were winged Mesopotamian lions[21] or bulls, with human heads.

A full and characteristic set shows the campaign leading up to the siege of Lachish in 701; it is the "finest" from the reign of Sennacherib, and now in the British Museum.

[23] He later wrote about a battle in Lachish: "And Hezekiah of Judah who had not submitted to my yoke ... him I shut up in Jerusalem his royal city like a caged bird.

An elaborate system of eighteen canals brought water from the hills to Nineveh, and several sections of a magnificently constructed aqueduct erected by Sennacherib were discovered at Jerwan, about 65 kilometres (40 mi) distant.

The complete destruction of Nineveh has traditionally been seen as confirmed by the Hebrew Book of Ezekiel and the Greek Retreat of the Ten Thousand of Xenophon (d. 354 BC).

Sir Walter Raleigh's notion that Nimrod built Nineveh has been disputed by eighteenth century scholar Samuel Shuckford.

[34] The discovery of the fifteen Jubilees texts found amongst the Dead Sea Scrolls has since shown that, according to the Jewish sects of Qumran, Genesis 10:11 affirms the apportionment of Nineveh to Ashur.

As recorded in Hebrew scripture, Nineveh was also the place where Sennacherib died at the hands of his two sons, who then fled to the vassal land of `rrt (Urartu).

The ruins of the "great city" Nineveh, with the whole area included within the parallelogram they form by lines drawn from the one to the other, are generally regarded as consisting of these four sites.

"[57] In 1842, the French Consul General at Mosul, Paul-Émile Botta, began to search the vast mounds that lay along the opposite bank of the river.

While at Tell Kuyunjiq he had little success, the locals whom he employed in these excavations, to their great surprise, came upon the ruins of a building at the 20 km far-away mound of Khorsabad, which, on further exploration, turned out to be the royal palace of Sargon II, in which large numbers of reliefs were found and recorded, though they had been damaged by fire and were mostly too fragile to remove.

The work of exploration was carried on by Hormuzd Rassam (an Assyrian), George Smith and others, and a vast treasury of specimens of Assyria was incrementally exhumed for European museums.

The British archaeologist and Assyriologist Professor David Stronach of the University of California, Berkeley conducted a series of surveys and digs at the site from 1987 to 1990, focusing his attentions on the several gates and the existent mudbrick walls, as well as the system that supplied water to the city in times of siege.

[75] After Mosul’s liberation from the control of the Islamic State (IS), Peter A. Miglus [de], University of Heidelberg, established a rescue project in 2018, exploring and documenting the intrusive IS tunnels in the Assyrian Military Palace that is located below the destroyed Mosque of the prophet Jonah on Tell Nebi Yunus.

[76][77] Subsequently, an extensive research project, currently under the direction of Stefan M. Maul, University of Heidelberg, developed, focusing also on other areas of Nineveh.

At Tell Kuyunjiq, activities started in 2021 with rescue and restoration measures for the destroyed reliefs in the throne room wing of the Southwest Palace.

Excavations in 1990 revealed a monumental entryway consisting of a number of large inscribed orthostats and "bull-man" sculptures, some apparently unfinished.

Five of the gateways have been explored to some extent by archaeologists: By 2003, the site of Nineveh was exposed to decay of its reliefs by a lack of proper protective roofing, vandalism and looting holes dug into chamber floors.

[91] On February 26, video footage showing ISIL destroying the smashing of statues and artifacts at the Mosul Museum[92] and are believed to have plundered others to sell overseas.

[93][94] Just a few days after the destruction of the museum pieces, Daesh terrorists demolished parts of three other major UNESCO world heritage sites, Khorsabad, Nimrud and Hatra.

[96] The results found that a few high-profile acts of deliberate vandalism were accompanied by much more extensive damage caused by construction and rubbish dumping extending across substantial parts of the site.

The 1962 Italian peplum film War Gods of Babylon is based on the sacking and fall of Nineveh by the combined rebel armies led by the Babylonians.

In the 1973 film The Exorcist, Father Lankester Merrin was on an archeological dig near Nineveh before returning to the United States and leading the exorcism of Regan MacNeil.