Asteroseismology

Stars have many resonant modes and frequencies, and the path of sound waves passing through a star depends on the local speed of sound, which in turn depends on local temperature and chemical composition.

Asteroseismology is closely related to helioseismology, the study of stellar pulsation specifically in the Sun.

Though both are based on the same underlying physics, more and qualitatively different information is available for the Sun because its surface can be resolved.

By linearly perturbing the equations defining the mechanical equilibrium of a star (i.e. mass conservation and hydrostatic equilibrium) and assuming that the perturbations are adiabatic, one can derive a system of four differential equations whose solutions give the frequency and structure of a star's modes of oscillation.

In non-rotating stars, modes with the same angular degree must all have the same frequency because there is no preferred axis.

The angular degree indicates the number of nodal lines on the stellar surface, so for large values of

, the opposing sectors roughly cancel out, making it difficult to detect light variations.

As a consequence, modes can only be detected up to an angular degree of about 3 in intensity and about 4 if observed in radial velocity.

By additionally assuming that the perturbation to the gravitational potential is negligible (the Cowling approximation) and that the star's structure varies more slowly with radius than the oscillation mode, the equations can be reduced approximately to one second-order equation for the radial component of the displacement eigenfunction

This basic separation allows us to determine (to reasonable accuracy) where we expect what kind of mode to resonate in a star.

Under fairly specific conditions, some stars have regions where heat is transported by radiation and the opacity is a sharply decreasing function of temperature.

By expanding and cooling slightly, the layer in the opacity bump becomes more opaque, absorbs more radiation, and heats up.

This continues until the material opacity stops increasing so rapidly, at which point the radiation trapped in the layer can escape.

In this sense, the opacity acts like a valve that traps heat in the star's envelope.

[5] Observations from the Kepler satellite revealed eccentric binary systems in which oscillations are excited during the closest approach.

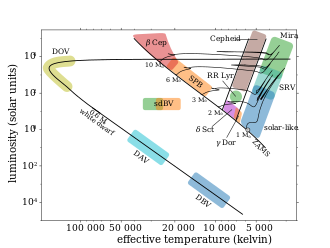

They principally oscillate at their fundamental modes, with typical periods ranging from days to months.

Cepheid pulsations are excited by the kappa mechanism acting on the second ionization zone of helium.

Delta Scuti variables are found roughly where the classical instability strip intersects the main sequence.

They are typically A- to early F-type dwarfs and subgiants and the oscillation modes are low-order radial and non-radial pressure modes, with periods ranging from 0.25 to 8 hours and magnitude variations anywhere between.

[clarification needed] Like Cepheid variables, the oscillations are driven by the kappa mechanism acting on the second ionization of helium.

The stars show multiple oscillation frequencies between about 0.5 and 3 days, which is much slower than the low-order pressure modes.

Gamma Doradus oscillations are generally thought to be high-order gravity modes, excited by convective blocking.

Following results from Kepler, it appears that many Delta Scuti stars also show Gamma Doradus oscillations and are therefore hybrids.

[7][8] Rapidly oscillating Ap stars have similar parameters to Delta Scuti variables, mostly being A- and F-type, but they are also strongly magnetic and chemically peculiar (hence the p spectral subtype).

Their dense mode spectra are understood in terms of the oblique pulsator model: the mode's frequencies are modulated by the magnetic field, which is not necessarily aligned with the star's rotation (as is the case in the Earth).

Subdwarf B (sdB) stars are in essence the cores of core-helium burning giants who have somehow lost most of their hydrogen envelopes, to the extent that there is no hydrogen-burning shell.

They have multiple oscillation periods that range between about 1 and 10 minutes and amplitudes anywhere between 0.001 and 0.3 mag in visible light.

The oscillations are low-order pressure modes, excited by the kappa mechanism acting on the iron opacity bump.

The oscillation periods broadly decrease with effective temperature, ranging from about 30 min down to about 1 minute.

A number of past, present and future spacecraft have asteroseismology studies as a significant part of their missions (order chronological).