Astor Place Riot

[2] It was the deadliest to that date of a number of civic disturbances in Manhattan, which generally pitted immigrants and nativists against each other, or together against the wealthy who controlled the city's police and the state militia.

At the same time, audiences had always treated theaters as places to make their feelings known, not just towards the actors, but towards their fellow theatergoers of different classes or political persuasions, and theatre riots were not a rare occurrence in New York.

British actors touring around the United States had found themselves the focus of often violent anti-British anger, because of their prominence and the lack of other visiting targets.

Forrest's muscular frame and impassioned delivery were deemed admirably "American" by his working-class fans, especially compared to Macready's more subdued and genteel style.

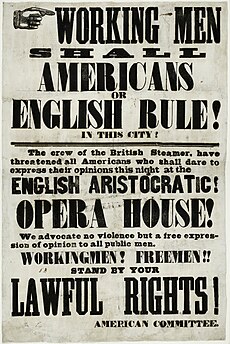

With its dress code of kid gloves and white vests, the very existence of the Astor Opera House was taken as a provocation by populist Americans for whom the theater was traditionally the gathering place for all classes.

[13] On May 7, 1849, three nights before the riot, Forrest's supporters bought hundreds of tickets to the top level of the Astor Opera House, and brought Macready's performance of Macbeth to a grinding halt by throwing at the stage rotten eggs, potatoes, apples, lemons, shoes, bottles of stinking liquid, and ripped up seats.

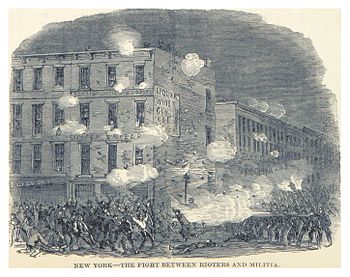

General Charles Sandford assembled the state's Seventh Regiment in Washington Square Park, along with mounted troops, light artillery, and hussars, a total of 350 men who would be added to the 100 policemen outside the theater in support of the 150 inside.

[citation needed] Fearing they had lost control of the city, the authorities called out the troops, who arrived at 9:15, only to be jostled, attacked, and injured.

[16] The New York Tribune reported: "As one window after another cracked, the pieces of bricks and paving stones rattled in on the terraces and lobbies, the confusion increased, till the Opera House resembled a fortress besieged by an invading army rather than a place meant for the peaceful amusement of civilized community.

"[17] The next night, May 11, a meeting was called in City Hall Park which was attended by thousands, with speakers crying out for revenge against the authorities whose actions they held responsible for the fatalities.

An angry crowd headed up Broadway toward Astor Place and fought running battles with mounted troops from behind improvised barricades,[4] but this time the authorities quickly got the upper hand.

Publisher James Watson Webb wrote: The promptness of the authorities in calling out the armed forces and the unwavering steadiness with which the citizens obeyed the order to fire on the assembled mob, was an excellent advertisement to the Capitalists of the old world, that they might send their property to New York and rely upon the certainty that it would be safe from the clutches of red republicanism, or chartists, or communionists [sic] of any description.

The elite's need for an opera house was met with the opening of the Academy of Music, farther uptown at 15th Street and Irving Place, away from the working-class precincts and the rowdiness of the Bowery.

[4] Though Forrest's reputation was badly damaged,[21] his heroic style of acting can be seen in the matinee idols of early Hollywood and performers such as John Barrymore.