Astronomical seeing

In astronomy, seeing is the degradation of the image of an astronomical object due to turbulence in the atmosphere of Earth that may become visible as blurring, twinkling or variable distortion.

The origin of this effect is rapidly changing variations of the optical refractive index along the light path from the object to the detector.

The strength of seeing is often characterized by the angular diameter of the long-exposure image of a star (seeing disk) or by the Fried parameter r0.

Both the size of the seeing disc and the Fried parameter depend on the optical wavelength, but it is common to specify them for 500 nanometers.

A seeing disk smaller than 0.4 arcseconds or a Fried parameter larger than 30 centimeters can be considered excellent seeing.

The best conditions are typically found at high-altitude observatories on small islands, such as those at Mauna Kea or La Palma.

[citation needed] In viewing a bright object such as Mars, occasionally a still patch of air will come in front of the planet, resulting in a brief moment of clarity.

This had the effect of having the image of the planet be dependent on the observer's memory and preconceptions which led the belief that Mars had linear features.

At large telescopes the long exposure image resolution is generally slightly higher at longer wavelengths, and the timescale (t0 - see below) for the changes in the dancing speckle patterns is substantially lower.

There are three common descriptions of the astronomical seeing conditions at an observatory: These are described in the sub-sections below: Without an atmosphere, a small star would have an apparent size, an "Airy disk", in a telescope image determined by diffraction and would be inversely proportional to the diameter of the telescope.

The effects of the atmosphere can be modeled as rotating cells of air moving turbulently.

The diameter of the seeing disk, most often defined as the full width at half maximum (FWHM), is a measure of the astronomical seeing conditions.

At the best high-altitude mountaintop observatories, the wind brings in stable air which has not previously been in contact with the ground, sometimes providing seeing as good as 0.4".

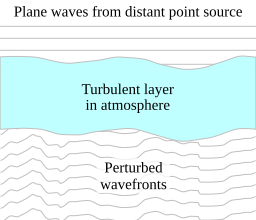

The diagram at the top-right of this page shows schematically a turbulent layer in the Earth's atmosphere perturbing planar wavefronts before they enter a telescope.

[3][4] This model is supported by a variety of experimental measurements[5] and is widely used in simulations of astronomical imaging.

The model assumes that the wavefront perturbations are brought about by variations in the refractive index of the atmosphere.

For all reasonable models of the Earth's atmosphere at optical and infrared wavelengths the instantaneous imaging performance is dominated by the phase fluctuations

For simplicity, the phase fluctuations in Tatarski's model are often assumed to have a Gaussian random distribution with the following second-order structure function:

is the atmospherically induced variance between the phase at two parts of the wavefront separated by a distance

For the Gaussian random approximation, the structure function of Tatarski (1961) can be described in terms of a single parameter

The refractive index fluctuations caused by Gaussian random turbulence can be simulated using the following algorithm:[7]

is the optical phase error introduced by atmospheric turbulence, R (k) is a two-dimensional square array of independent random complex numbers which have a Gaussian distribution about zero and white noise spectrum, K (k) is the (real) Fourier amplitude expected from the Kolmogorov (or Von Karman) spectrum, Re[] represents taking the real part, and FT[] represents a discrete Fourier transform of the resulting two-dimensional square array (typically an FFT).

The assumption that the phase fluctuations in Tatarski's model have a Gaussian random distribution is usually unrealistic.

A more thorough description of the astronomical seeing at an observatory is given by producing a profile of the turbulence strength as a function of altitude, called a

The first answer to this problem was speckle imaging, which allowed bright objects with simple morphology to be observed with diffraction-limited angular resolution.

Starting in the 1990s, many telescopes have developed adaptive optics systems that partially solve the seeing problem.

The best systems so far built, such as SPHERE on the ESO VLT and GPI on the Gemini telescope, achieve a Strehl ratio of 90% at a wavelength of 2.2 micrometers, but only within a very small region of the sky at a time.

A wider field of view can be obtained by using multiple deformable mirrors conjugated to several atmospheric heights and measuring the vertical structure of the turbulence, in a technique known as Multiconjugate Adaptive Optics.

It does require very much longer observation times than adaptive optics for imaging faint targets, and is limited in its maximum resolution.

[citation needed] Much of the above text is taken (with permission) from Lucky Exposures: Diffraction limited astronomical imaging through the atmosphere, by Robert Nigel Tubbs.