Atlas Comics (1950s)

[1] Magazine and paperback novel publisher Martin Goodman, whose business strategy involved having a multitude of corporate entities, used Atlas as the umbrella name for his comic-book division during this time.

Atlas evolved out of Goodman's 1940s comic-book division, Timely Comics, and was located on the 14th floor of the Empire State Building.

[12] The Atlas logo united a line put out by the same publisher, staff and freelancers through 59 shell companies, from Animirth Comics to Zenith Publications.

[14][15] Atlas attempted to revive superheroes in Young Men #24-28 (Dec. 1953 - June 1954) with the Human Torch (art by Syd Shores and Dick Ayers, variously), the Sub-Mariner (drawn and most stories written by Bill Everett) and Captain America (writer Stan Lee, artist John Romita Sr.).

[19][20]: 67–68 As Marvel/Atlas editor-in-chief Stan Lee told comic-book historian Les Daniels, Goodman "would notice what was selling, and we'd put out a lot of books of that type."

Commented Daniels, "The short-term results were lucrative; but while other publishers took the long view and kept their stables of heroes solid, Goodman let his slide.

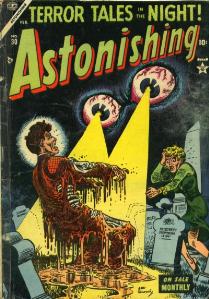

"[20]: 57 While Atlas had some horror titles, such as Marvel Tales, as far back as 1949, the company increased its output dramatically in the wake of EC's success.

"[20]: 67–68 Until the early 1960s, when Lee, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko would help revolutionize comic books with the advent of the Fantastic Four and Spider-Man, Atlas was content to flood newsstands with profitable, cheaply produced product — often, despite itself, beautifully rendered by talented if low-paid artists.

[21] The Atlas "bullpen" had at least five staff writers (officially called editors) besides Lee: Hank Chapman, Paul S. Newman, Don Rico, Carl Wessler, and, in the teen humor division, future Mad magazine cartoonist Al Jaffee.

[25] The next generation included the prolific and much-admired Joe Maneely, who before his death just prior to Marvel's 1960s breakthrough was the company's leading artist,[26] providing many covers and doing work in all genres, most notably on Westerns and on the medieval adventure Black Knight.

[32] One of the most long-running titles was Millie the Model, which began as a Timely Comics humor series in 1945 and ran into the 1970s, lasting for 207 issues and launching spinoffs along the way.

[39] Miscellaneous titles included the espionage series Yellow Claw, with Maneely, Severin, and Jack Kirby art; the Native American hero Red Warrior, with art by Tom Gill;[40] the space opera Space Squadron, written and drawn by future Marvel production executive Sol Brodsky;[41] and Sports Action, initially featuring true-life stories about the likes of George Gipp and Jackie Robinson, and later fictional features of, as one cover headline put it, "Rugged Tales of Danger and Red-Hot Action!".

As comic-book historian Gerard Jones explains, the company in 1956 ...had been found guilty of restraint of trade and ordered to divest itself of the newsstands it owned.

[45] With no other options, Goodman turned to the distributor Independent News, owned by rival National Periodical Publications, the future DC Comics, which agreed to distribute him on constrained terms that allowed only eight titles per month.

[49]During this retrenchment, according to a fabled industry story, Goodman discovered a closet-full of unused, but paid-for, art, leading him to have virtually the entire staff fired while he used up the inventory.

In the interview noted above, Lee, one of the few able to give a firsthand account, told a seemingly self-contradictory version of the downsizing: It would never have happened just because he opened a closet door.

[49]In a 2003 interview, Joe Sinnott, one of the company's top artists for more than 50 years, recalled Lee citing the inventory issue as a primary cause.

Artist Jack Kirby — who had amicably split with creative partner Joe Simon a few years earlier, and separately lost a lawsuit to a DC Comics editor — was having difficulty finding work.

Now, beginning with the cover and the seven-page story "I Discovered the Secret of the Flying Saucers" for Strange Worlds #1 (Dec. 1958), Kirby returned for a 12-year run that would soon help revolutionize comics.

"The tales had Kirby's energy and, courtesy of Lee, confessional, first-person titles typical of sensation-mongering tabloids and comics, such as, 'I Created Sporr, the Thing That Could Not Die!

This was followed by one or two twist-ending thrillers or sci-fi tales drawn by Don Heck, Paul Reinman, or Joe Sinnott, all capped by an often-surreal, sometimes self-reflexive short by Lee and artist Steve Ditko.

Lee in 2009 described these "short, five-page filler strips that Steve and I did together", originally "placed in any of our comics that had a few extra pages to fill", as "odd fantasy tales that I'd dream up with O. Henry-type endings."

"[56] Although for several months in 1949 and 1950 Timely's titles bore a circular logo labeled "Marvel Comic", the first modern comic books so labeled were the science fiction anthology Journey into Mystery #69 and the teen humor title Patsy Walker #95 (both June 1961), which each showed an "MC" box on its cover.

Note: The romance title Linda Carter, Student Nurse #1–9 (Sept. 1961 – Jan. 1963), sometimes grouped together with Atlas Comics, chronologically falls within Marvel, and all covers have the "MC" box.