Atomic electron transition

[2] The time scale of a quantum jump has not been measured experimentally.

However, the Franck–Condon principle binds the upper limit of this parameter to the order of attoseconds.

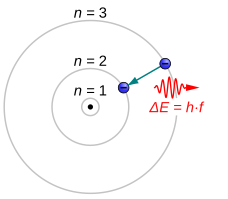

[3] Electrons can relax into states of lower energy by emitting electromagnetic radiation in the form of a photon.

The larger the energy separation between the electron's initial and final state, the shorter the photons' wavelength.

[4] Danish physicist Niels Bohr first theorized that electrons can perform quantum jumps in 1913.

[5] Soon after, James Franck and Gustav Ludwig Hertz proved experimentally that atoms have quantized energy states.

[6] The observability of quantum jumps was predicted by Hans Dehmelt in 1975, and they were first observed using trapped ions of barium at University of Hamburg and mercury at NIST in 1986.

[4] An atom interacts with the oscillating electric field: with amplitude

The atom can also interact with the oscillating magnetic field produced by the radiation, although much more weakly.

The Hamiltonian for this interaction, analogous to the energy of a classical dipole in an electric field, is

The stimulated transition rate can be calculated using time-dependent perturbation theory; however, the result can be summarized using Fermi's golden rule:

The angular integral is zero unless the selection rules for the atomic transition are satisfied.

In 2019, it was demonstrated in an experiment with a superconducting artificial atom consisting of two strongly-hybridized transmon qubits placed inside a readout resonator cavity at 15 mK, that the evolution of some jumps is continuous, coherent, deterministic, and reversible.

[8] On the other hand, other quantum jumps are inherently unpredictable.